You are here

A key assessment of poverty in America is the Official Poverty Measure (OPM), which is calculated by the United States Census Bureau using a range of income and economic data. The methodology used to determine the OPM is considered by many to be outdated and inaccurate, however, and policymakers have been considering updates to the measure for quite some time. Even small changes to this measurement could have wide-ranging repercussions beyond simply defining the number of people living in poverty. Potential changes to the OPM could also affect eligibility for a range of government benefits and therefore, our fiscal outlook. Here’s an overview of how poverty is measured, concerns about the poverty measure, and the potential effect of proposed changes.

How is Poverty Measured?

A fundamental part of measuring poverty is a comparison between a household’s income and the cost of basic necessities. The comparison has three components:

- The first component of the OPM — poverty thresholds — is a calculation of the cost of a household’s basic needs. Those needs were initially defined in the early 1960s as being three times what an average family spent on food, according to the 1955 Household Food Consumption Survey. Currently there are 48 thresholds, which vary by family size and family composition, but not by geography. The methodology for the calculation has not changed since it was introduced, but instead has been updated each year for inflation. In 2018, the poverty threshold for a single person under the age of 65 was $13,064.

- The second component involves measuring pre-tax cash income. Such income comes from sources like wages, unemployment and worker’s compensation, Social Security and Supplemental Security Income, child support, interest, and dividends. Non-cash benefits such as those from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program are not included. The methodology for calculating the income component also has not changed since the 1960s.

- A third component of the OPM is inflation — the increase in the prices of goods and services. This number is used to adjust the thresholds each year; it can be measured in various ways and is currently being reviewed by the Trump administration. The adjustment currently being used is based on the consumer price index for urban consumers (CPI-U).

Terminology

There are two important terms that relate to how the OPM is used by certain programs, as well as how it is discussed more generally.

- Poverty Guidelines: Poverty guidelines are a simplified version of poverty thresholds. They define the range of financial eligibility for certain federal programs including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and the Community Services Block Grant program.

- The Poverty Rate: Broadly speaking, the poverty rate is the percentage of people whose pre-tax income falls below a certain dollar amount. It is the statistic most widely used to describe the percentage of the population living in poverty. The poverty rate helps to track trends in poverty over time and across different demographic groups. In 2018, the poverty rate was 11.8 percent.

Are Our Measures of Poverty Accurate?

Many people believe that the current system for measuring poverty is flawed. Arguments center around the methods used to calculate the poverty thresholds and the measure used to calculate income; such arguments include:

- The methodology used to calculate the poverty thresholds is old.

- The thresholds do not take into account geographical variations in cost of living.

- The inflation measures could be more accurate.

- The income measures over-estimate resources because they do not take into account circumstances for people with additional expenses (for example, those who are disabled).

- The income measures can under-estimate resources because they fail to take into account tax credits, housing subsidies, or other forms of assistance.

Are There Ways to Improve How We Measure Poverty?

In light of the flaws in how poverty is calculated and the importance of these measures for many government programs, alternative measures for a number of the OPM’s components have been put forward.

Supplemental Poverty Measure

In addition to the OPM, there are a number of other options to measure poverty. The most well-known is the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM). That measure helps to provide a deeper understanding of poverty and economic conditions by incorporating the effects of tax credits, housing subsidies, food assistance programs, work expenses, and medical costs.

Because the official measure does not account for taxes and non-cash transfers, one of the important aspects of the SPM is that it sheds light on the effect of government anti-poverty programs. It is also useful for considering the effects of “nondiscretionary” expenses such as those for health care.

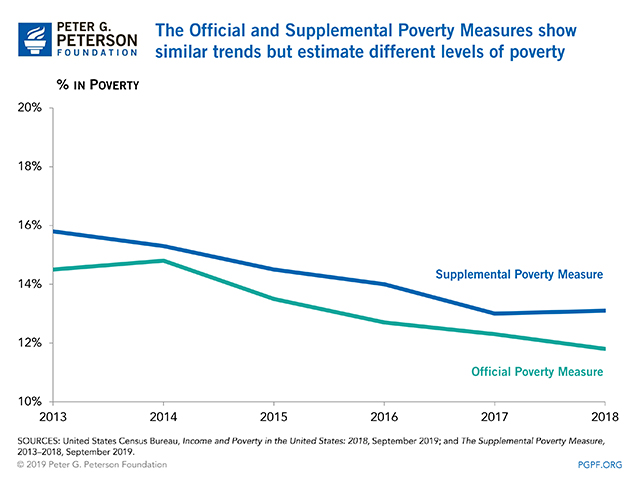

In 2018, the SPM was higher than the official poverty measure; it showed that 13.1 percent of people were poor, 1.3 percentage points above the official measure. Differences between the two measures are more significant for certain age groups. For example, the SPM shows higher poverty rates among adults 65 years and older as a result of how it measures resources and households.

Alternate Inflation Measures

Certain policymakers and economists support using the chained CPI instead of the CPI-U, arguing that the chained CPI provides a more accurate estimate of the changes in the cost of living by reducing the substitution bias, which occurs when consumers substitute one good for another as prices rise. Both indices are designed to measure price changes of about 80,000 items across the country on a monthly basis. However, the chained CPI better reflects changes in consumer buying patterns because it measures what people buy in the periods before and after a price change.

Using the chained CPI to adjust the OPM for inflation would result in a lower measure of poverty. Furthermore, the difference between the new OPM and the one calculated under the current inflation factor would grow every year. Fewer people would be considered poor using the chained CPI and therefore many people receive fewer (or no) benefits from programs that use the OPM to determine eligibility.

In addition, while measuring inflation accurately is important, concerns exist that the chained CPI may not be accurate for low-income households because their spending patterns and needs are different than those of middle- and high-income households.

Poverty and the Federal Budget

While there are many federal programs that benefit low-income beneficiaries, a group of programs (called means-tested or need-tested) specifically target those with relatively low income or few assets. Such programs include Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, child nutrition, housing assistance, and education (such as the Pell Grant Program).

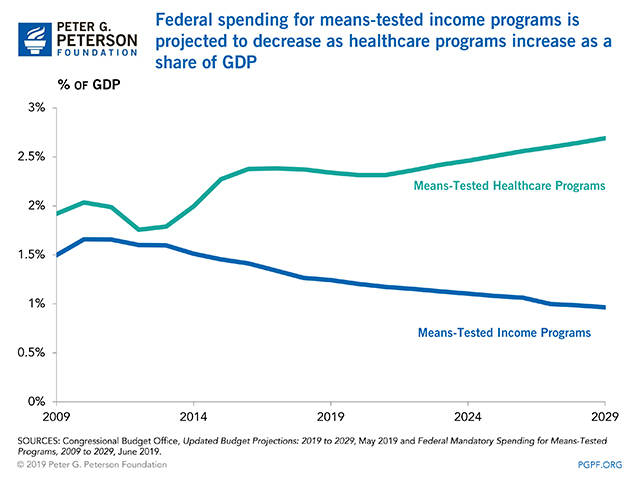

CBO estimates that 18 percent of the federal budget is devoted to means-tested programs; many of those programs also receive funding from state governments. The majority of such spending on the federal level goes to healthcare programs — in particular, for Medicaid. Income security programs — such as Supplemental Security Income, the earned income and child tax credits, and family support and foster care — account for most of the remaining means-tested federal spending. Projections show that, if laws remain unchanged, spending for means-tested programs will rise more slowly than spending in other areas of the budget.

Conclusion

While the measurement of poverty will always include a degree of subjectivity, policymakers should strive to be as accurate as possible, so that government programs and benefits reach those who need them the most. After all, the programs that use the poverty guidelines are relied upon by millions of Americans and are vital for mitigating income inequality and creating a more robust economy. As policymakers consider changes to how poverty is measured, they should do so with a clear understanding of their spending priorities; given the limited resources at their disposal, fiscal responsibility will be necessary to ensure that funding is available to protect the most vulnerable.