You are here

Budget Process

Policymakers use the federal budget process to establish spending priorities and to determine who will pay for those activities. Those decisions affect the lives of all Americans, as well as the nation’s economy. The size and scope of such decisions make the budget process one of the most important and complex exercises in public policymaking.

The formulation of the budget is an annual process that involves the Congress, the White House and virtually all federal agencies. In truth, lawmakers do not actually approve a single budget.

Instead, the federal budget comprises many separate documents and pieces of legislation.

- One of the important documents is the President’s annual budget proposal, which lays out the Administration’s budget priorities in detail. The Congress has never voted to accept the President’s budget in its entirety, but it acts as a comprehensive statement of an administration’s priorities.

- The Congress has its own process to set its priorities: The House and Senate are each supposed to prepare a budget resolution that serves as a broad framework for the many separate pieces of legislation that will determine spending, revenues, deficits, and debt. The two sides of Congress are then supposed to reconcile their separate plans to agree on a concurrent resolution. Such compromise usually occurred through 2010, but since then, sharp disagreements about fiscal policy have prevented the Congress from agreeing on an overall budget plan. Budget resolutions are not presented to the President to sign, so they do not become law. In fact, because funding can also be provided through other means, a budget resolution is not necessary for much of the annual budget process to occur.

- Twelve appropriation subcommittees in each congressional body manage legislation to fund the annual operations of government.

- House and Senate authorization committees have oversight over tax law and entitlement programs.

- Finally, the president must sign any legislation passed by the Congress before it goes into effect.

Budget Process Timeline

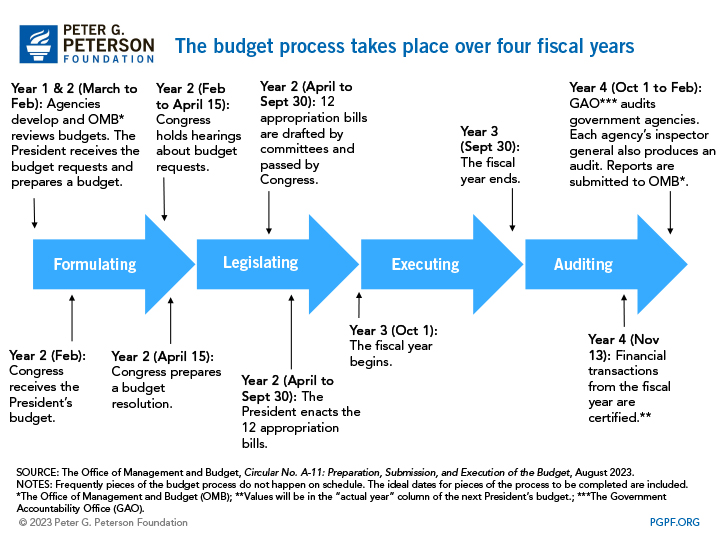

From start to finish, the process of formulating, legislating, executing, and auditing the budget lasts over a period of four fiscal years.

Throughout most of that cycle, economic and political conditions can change. In response, policymakers can add or subtract funds from programs or activities; they can also extend, terminate, or modify revenue provisions.

Sticking to the Budget

Once policymakers agree on a budget framework, there are procedural and statutory provisions intended to help keep the budget on track. While those restrictions cannot substitute for consensus about fiscal goals, they can help impose needed budget discipline during the legislative process. Budget enforcement provisions often apply to multiple years and make it harder to enact changes to revenues or spending that would be inconsistent with the agreed-upon framework. Lawmakers are able to change the restrictions, but if the provisions are set in statute, Congress must pass and the President must sign a new law to modify or terminate them.

The best-known enforcement provisions include spending caps, pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) requirements, and sequestration (or across-the-board spending reductions).

- Statutory caps on appropriations limit the amount of such spending allowed each year. For example, spending caps were in effect from 2012 through 2021 for annually appropriated, or discretionary, spending. No caps were in place for 2022 and 2023, but the Fiscal Responsibility Act established caps for fiscal years 2024 and 2025. The caps are meant to provide budget discipline and force lawmakers to trade lower priority programs for higher priority needs. To provide a safety valve, some types of spending, such as spending for disaster relief or other emergencies, are not constrained by the caps. If spending exceeds the allowed level, a process known as sequestration enforces the limits by cutting spending on certain programs across the board by a uniform percentage. (See further below.)

- Pay-as-you-go rules, commonly known as “PAYGO”, require that legislated changes to mandatory programs and revenues must not increase the deficit. Versions of such rules currently exist in statute as well as part of House and Senate rules.

- Sequestration is the process used to enforce spending limits and statutory PAYGO. It imposes across-the-board cuts in certain programs to reduce spending enough to eliminate a deficit increase that results from legislation subject to caps or statutory PAYGO. Sequestration is intended to be a blunt instrument that policymakers would seek to avoid because it automatically cuts spending regardless of the impact on programs. However, lawmakers have exempted many programs from sequestration — for example, Social Security and Medicaid. Those exemptions increase the size of potential across-the-board cuts to programs that remain subject to sequestration.

Budgeting is always difficult due to competing priorities and the important issues at stake. Without compromise and consensus, the process can "gridlock." In its most extreme form, gridlock can interrupt funding, disrupting federal operations and eroding the public’s confidence in the government’s ability to manage its affairs. That is another reason why it is important for lawmakers to agree to put the budget on a sustainable long-term path — a sustainable long-term plan can accommodate short-term priorities, while also giving the nation a stable fiscal outlook.