Inflation, Interest Rates, And The Budget: New Challenges, Old Solutions

By William G. Gale and Swati Joshi

This paper is part of an initiative from the Peterson Foundation to help illuminate and understand key fiscal and economic questions facing America. See more papers in the Expert Views: Inflation, Interest, and the National Debt series.

As if navigating the COVID pandemic was not enough of a fiscal challenge, policymakers must now confront the rebound of inflation and interest rates. Higher interest rates exacerbate an already-unsustainable long-term fiscal trajectory. Inflation generally works in the other direction, eroding the real value of the debt, but it is not a long-term solution.

The more things change, though, the more they remain the same. Despite the recent change in economic conditions, the “secret sauce” that would generate an enduring fiscal solution has not changed — nor is it very secret. The same old (un)tried and true options that have been discussed before, raising revenues and decelerating spending growth, are the only way out.

A. How We Got Here

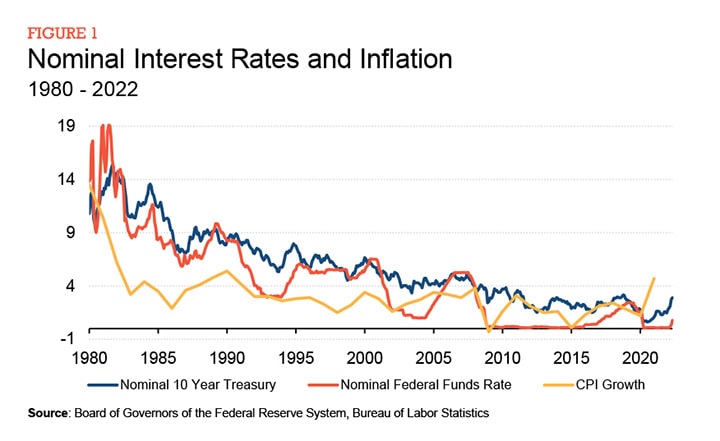

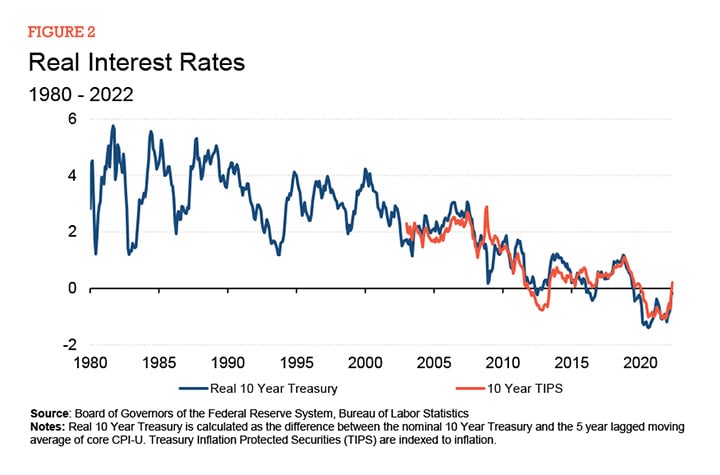

Starting in the 1980s, the nominal interest rate on government debt (10-year Treasuries) fell, at first precipitously and then gradually through 2020 (Figure 1). Inflation rates similarly fell and remained low and relatively stable for the past three decades. Real interest rates on government debt — as measured by the difference between the 10-year Treasury nominal rate and 5-year lagged CPI inflation or by the return on Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities — also fell (Figure 2). Falling interest rates were not just an American phenomenon: several European governments — including Switzerland, Denmark, Austria, and Germany — have paid negative nominal interest rates in recent years.

These interest rate trends reflect both reductions in overall rates of return on all assets as well as a flight to safety. Rate of return have been reduced by a world-wide saving glut. This increased saving was caused by changes in demographics, the distribution of income, and productivity growth, and by rapid growth in countries with high saving rates. The flight to safety reflects a response to increased risk, the fact that advanced economies (which generate safe assets) have grown at a slower rate than the rest of the world, and new rules and regulations that required financial institutions to hold more safe assets.

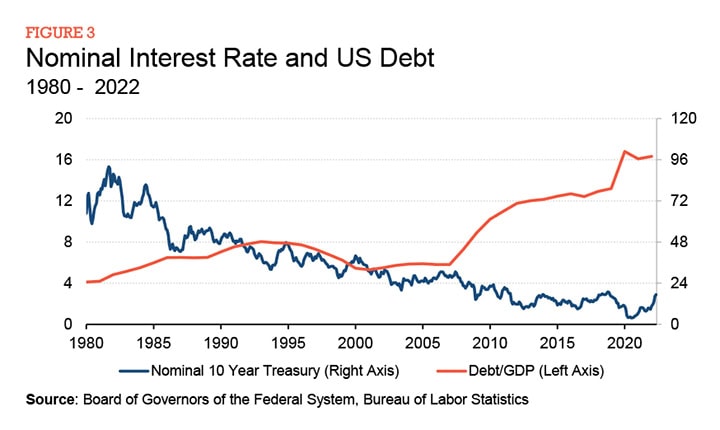

Notably, lower government interest rates occurred over a period when government debt rose precipitously, from about 39 percent of GDP in 2007 to 100 percent of GDP by 2020 (Figure 3).

But economic conditions are now changing: the rate of inflation has increased, reaching a 40-year high of 9.1 percent per annum in June 2022. Importantly, inflation has risen in most advanced economies around the world; it is not solely an American phenomenon.

Higher US inflation reflects the confluence of many factors, some of which are global in nature. Consumer demand has increased due to constrained spending during the pandemic, income support in the Biden Administration’s American Rescue Plan, and the Fed’s expansive monetary policy stance over the past few years. Supply chain issues — international in scope and affecting the provision of goods, services, and labor — have played a key role in pushing up prices. The Russian invasion of Ukraine boosted commodity prices by creating current supply constraints and concerns that the war will disrupt future supply (although commodity prices have fallen from their peaks). And firms in concentrated industries have seen rising profits despite inflation, implying that they are marking up prices due to their increased market power. Extraordinary price increases in the goods sector were the primary driver of inflation through much of 2021, but prices in the service sector have recently accelerated.

In response to higher inflation, the Fed has raised its target federal funds rate four times in the first seven months of 2022 — most recently by 0.75 basis points — to between 2.25 and 2.5 percent. Nevertheless, nominal interest rates on government debt remain far below the rate of inflation. As a result of negative real interest rates and strong economic growth in 2021, the debt/GDP ratio fell in 2021 even though the federal deficit was 12.4 percent of GDP.

B. Where We Are Headed

The future paths of inflation and interest rates will have important impacts on the long-term federal budget outlook.

Inflation erodes the value of the debt but is not a long-term solution. This is because most government bonds are relatively short-term, so investors would require higher interest rates on bond issues once it became clear that the US was trying to inflate away the debt. And most of our long-term debt takes the form of obligations that are either explicitly or implicitly tied to inflation (payments to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid participants).

Higher rates raise net interest outlays, which were 1.6 percent of GDP as of 2021. Although this figure is not high relative to historical norms, government debt currently equals 98 percent of GDP — almost an all-time high — and is projected to rise inexorably in the future. Having a large initial debt implies that future interest payments as a share of GDP will be sensitive to the level of interest rates.

CBO estimates a debt-to-GDP ratio of 185 percent in 2052 under current-law assumptions. In this scenario, the average government interest rate on government debt rises from 1.76 percent in 2022 to 4.1 percent in 2052. CBO shows further that if the average nominal government interest rate is boosted, relative to the baseline assumptions, by a differential starting at 5 basis points in 2022 and increasing by 5 basis points each year (before macroeconomic responses), the debt-GDP ratio would rise to 235 percent in 2052. On the other hand, if the average nominal government interest rate falls at the same differential as above, debt-GDP ratio would be 147 percent of GDP in 2052.

As an extreme (and unlikely) example of how results might differ at the 30-year horizon, we estimate a scenario under current law where the average nominal interest rate paid by the government remains constant through 2052 at the 2023 level projected in the May 2022 baseline. In that scenario, debt rises to 134 percent of GDP by 2052 and net interest payments rise to 2.3 percent of GDP. These figures are substantially lower than the 185 percent debt-to-GDP ratio and 7.0 percent net interest-to-GDP ratio projected under the current law baseline with rising interest rates, but they are still substantially higher than the current values of debt and interest payments.

C. Solutions

There is widespread agreement that the long-term budget outlook is unsustainable — even in relatively low interest rate environments. As the economist Herb Stein used to say, “Something that can’t go on forever will stop.” But how it stops matters, and we need a plan to address the long-term fiscal challenge that gives the economy a smooth landing.

To address current fiscal imbalances, policymakers should enact a gradual, phased in, long-term plan that would reduce primary deficits substantially over time and eventually stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio at a plausible level. It’s time for them to finally use the “secret sauce”: increase revenues and decelerate spending.

To increase revenues, we need reform that is fiscally responsible, raises taxes on wealthy households, and tightens the enforcement of taxes. This includes closing capital gains loopholes, repealing several features of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, simplifying our current corporate income tax, and better funding the IRS. Beyond this, policymakers should think about new taxes, such as a broad-based national consumption tax or a carbon tax.

To decelerate spending, policymakers must reduce the growth rate of current entitlement spending: healthcare spending (most prominently Medicare and Medicaid) already makes up a significant portion of the federal budget, which will only grow as the population continues to age, and Social Security is currently on track to be illiquid starting in 2035.

Policymakers have a big challenge in front of them. The recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act is a good first step, allocating $300 billion for deficit reduction, paid for mainly through a 15 percent corporate minimum tax and stronger IRS enforcement. But there is still work to do, because letting the debt continue to rise will undoubtedly have adverse consequences for our economy, our children, and their future.

About the Authors

William Gale is the Arjay and Frances Fearing Miller Chair in Federal Economic Policy and a senior fellow in the Economic Studies program at the Brookings Institution. His research focuses on tax policy, fiscal policy, pensions, and saving behavior. He is co-director of the Tax Policy Center, a joint venture of the Brookings Institution and the Urban Institute. He is also director of the Retirement Security Project.

Gale is the author of Fiscal Therapy: Curing America’s Debt Addiction and Investing in the Future (Oxford University Press, 2019).

He is also the co-editor of several books, including Automatic: Changing the Way America Saves (Brookings 2009); Aging Gracefully: Ideas to Improve Retirement Security in America (Century Foundation, 2006); The Evolving Pension System: Trends, Effects, and Proposals for Reform (Brookings, 2005); Private Pensions and Public Policy (Brookings, 2004); Rethinking Estate and Gift Taxation (Brookings, 2001), and Economic Effects of Fundamental Tax Reform (Brookings, 1996).

His research has been published in several scholarly journals, including the American Economic Review, Journal of Political Economy, and Quarterly Journal of Economics. In 2007, a paper he co-authored was awarded the TIAA-CREF Paul A. Samuelson Award Certificate of Excellence.

He has also written extensively in policy-related publications and newspapers, including op-eds in CNN, the Financial Times, Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post.

He served as president of the National Tax Association from 2019 to 2020 and as vice president of Brookings and director of the Economic Studies program from 2006 to 2009. Prior to joining Brookings in 1992, he was an assistant professor in the Department of Economics at the University of California, Los Angeles, and a senior economist for the Council of Economic Advisers under President George H.W. Bush.

He is a member of the Macroeconomic Advisers Board of Advisors since 2016. Gale has consulted for the MSL Group and in 2017 was a panelist at the Center for Strategic Development's Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Economic Reforms Workshop.

Gale attended Duke University and the London School of Economics and received his Ph.D. from Stanford University in 1987. He lives in Fairfax, Virginia, is an avid tennis player, and is a person who stutters. He is married to Diane Lim and is the father of two grown children.

Swati Joshi is a senior research assistant at the Brookings Institution and the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, where she has specialized in tax and fiscal policy. Prior to Brookings, she worked at McKinsey Global Institute on the Economics Research Team. She received a BS in Economics and Mathematics from Northeastern University. She is a proud alumna of Fiscal Challenge, where her team was a finalist in 2018.

Expert Views

Inflation, Interest, and the National Debt

We asked experts with diverse views from across the political spectrum to share their perspectives and insights to help understand the landscape and identify solutions.