Inflation Fighting And Ensuring Fiscal Health Starts Now

By Dana M. Peterson and Lori Esposito Murray

This paper is part of an initiative from the Peterson Foundation to help illuminate and understand key fiscal and economic questions facing America. See more papers in the Expert Views: Inflation, Interest, and the National Debt series.

Inflation and rising interest rates will have seriously negative effects on the United States’ fiscal outlook. Inflation’s impact on a fiscal budget could be viewed as a neutralizer: on the one hand raising revenues and making annual federal budget deficits and accumulated public debt smaller in real terms, while, at the same time, raising the costs of goods and services which further inflate government expenditures, worsening fiscal gauges, which are usually monitored in nominal terms. But the challenge is the already very large and accumulated debt and the rising cost of servicing it as interest rates rise, compounding the amount of public debt owed and shrinking the budget resources available to address the needs of the nation or its ability to respond to a crisis. While the challenge may be cataclysmic, it is not imminent, providing sufficient time for leaders to address it, if we start now.

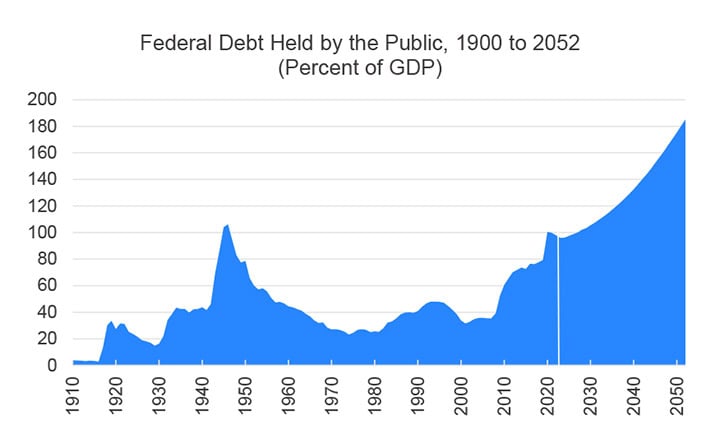

CBO Estimates US Public Debt to Swell to More Than 185 Percent by 2050

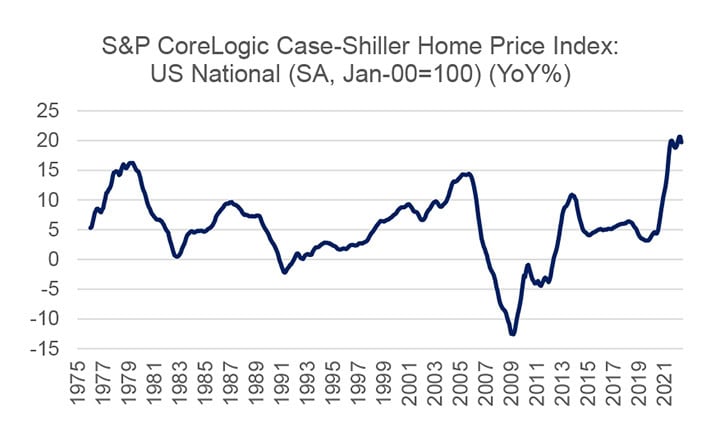

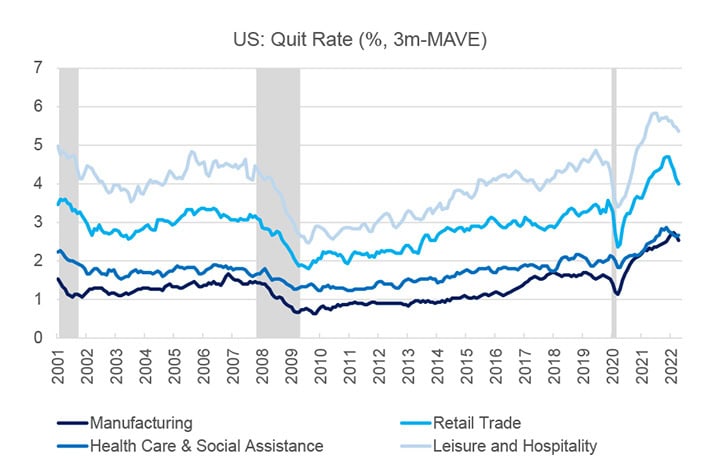

Inflation to-date has been fueled by both demand and supply drivers, which present a serious problem to the economic and fiscal health of the United States. Demand drivers include powerful household demand for goods during the worst of the pandemic, and now strong demand for services now that the pandemic is in the rearview mirror. Additionally, low interest rates fueled demand for homes and financed goods like automobiles. Supply drivers include shortages of food, energy, metals, rare gasses, cooking oils, and fertilizers due to the war in Ukraine, plus higher costs for transportation and semiconductors which require raw materials from Russia and Ukraine for operation/production. Continued supply chain bottlenecks associated with China’s zero-covid policy, and rising wages due to labor shortages and the “Great Resignation” are also supply-side drivers of inflation.

Rising Home Valuations Swell Shelter Costs

Great Resignation Exacerbates Labor Shortages

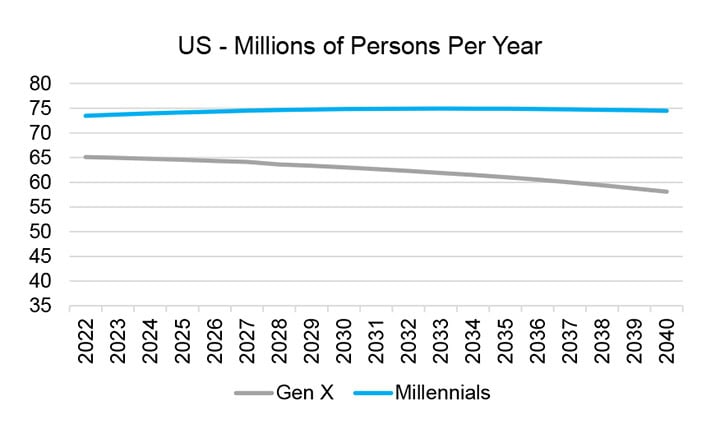

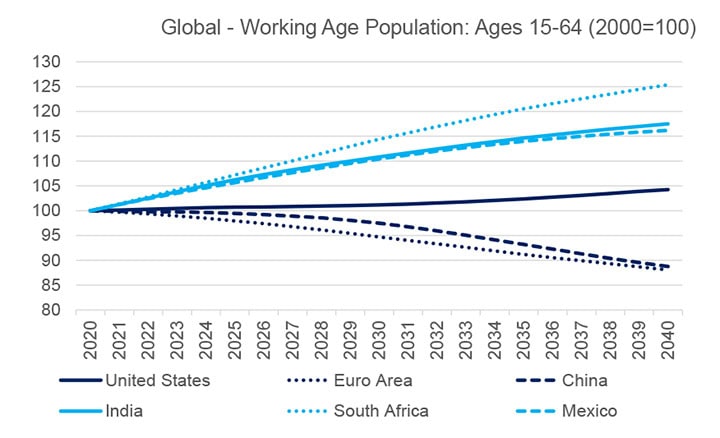

However, a higher inflationary environment (i.e., rate exceeding 2 percent year-over-year) compared to the pre-pandemic norm is likely here to stay for several more years. Persistent inflation drivers include continued millennial housing demand as 73 million Americans in this cohort reach peak earnings over the next twenty years. Labor shortages fueled by an aging demographic, a lack of public/private collaboration on policies that promote work (e.g., training and upskilling programs, paid family leave, subsidized childcare and adult care), and tight immigration policies that limit the number of foreign workers will continue to drive up wages that are ultimately passed onto consumers. Deglobalization, characterized by reorientation of supply chains and manufacturing back to the U.S. or to locales that are more secure (e.g., friend-shoring) but less cost effective will drive up costs for businesses.

Additionally, the greening of the U.S. economy will involve steep transition costs for building out new infrastructure, creating new businesses, and sunsetting obsolete ones away from reliance on fossil fuels. The federal government will need to pay for these costs in terms of higher cost-of-living adjustments for entitlement programs, higher wages for workers and contractors, and elevated materials costs for maintenance and new projects. These elevated costs will translate into larger annual federal budget deficits and further accumulation of public debt. Moreover, they will be even further exacerbated unless the U.S. develops a comprehensive energy transition policy that takes into account the challenges of energy independence and security, in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Millennials Will Fuel Future Housing Demand

Labor Shortages to Persist with Aging Workforce

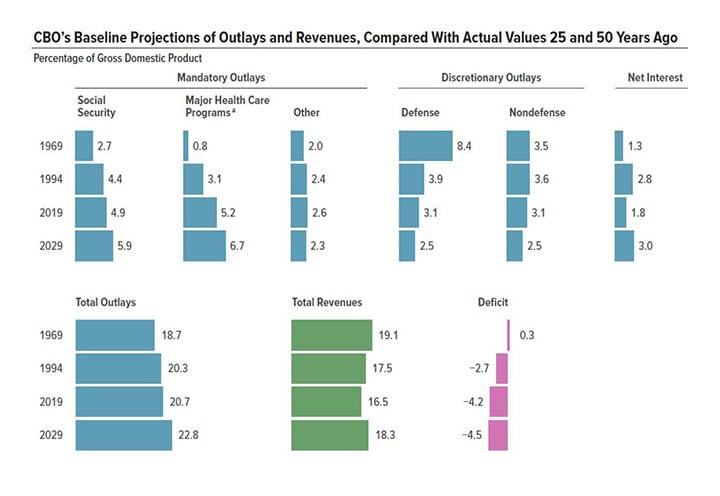

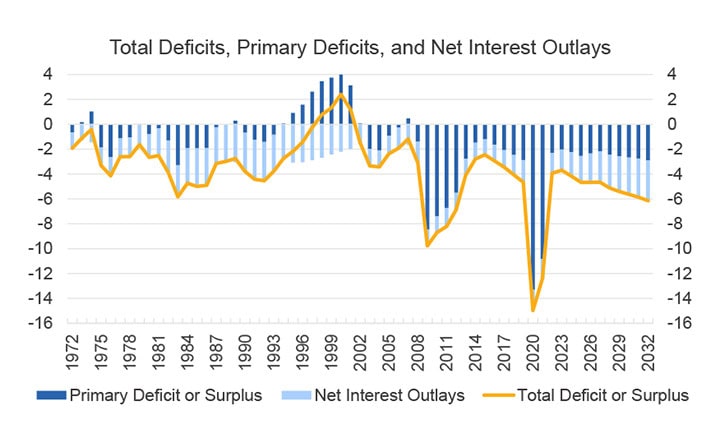

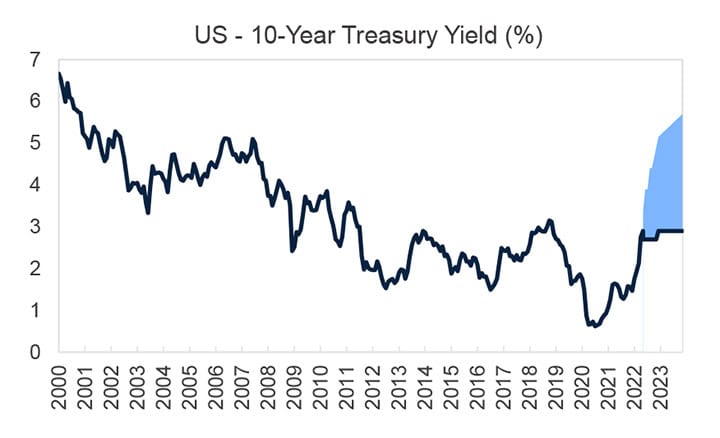

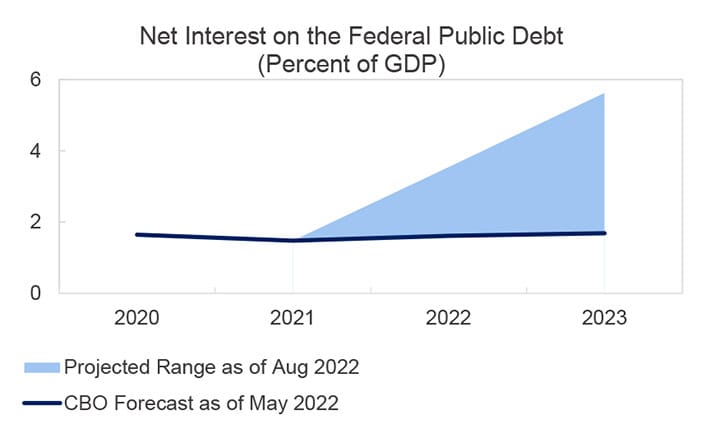

Outsized past annual federal budget deficits due to a combination of fiscal stimulus and tax cuts, but no accompanying spending cuts, have bloated the debt to an astounding share of U.S. GDP. Going forward debt will continue to accumulate unless reforms are undertaken due to explosive spending on entitlement programs for Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, and a tax system that is too complex and distorts taxpayer economic choices. Additionally, debt service (i.e., the interest on the public debt) will grow exponentially. Indeed, the Fed’s interest rate tightening cycle is ramping up the pace of increase in debt service as we speak. Debt service as a percent of GDP may climb as high as 6 percent by the end of 2023 consistent with the interest rate on the public debt’s typical tracking of 10-year Treasury yields, which are rising with Fed rate hikes.

Entitlement Program Outlays to Expand Ahead

Debt Service to Grow in Share of Annual Deficits

Strong Relationship Between 10-Year TSY and Interest Rate on Public Debt

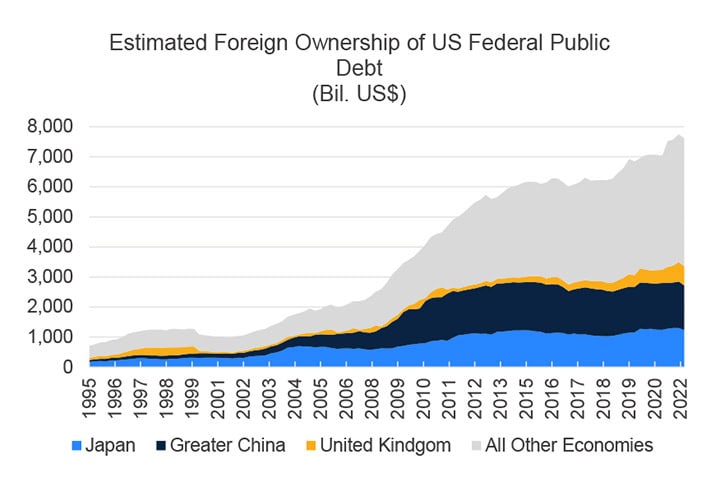

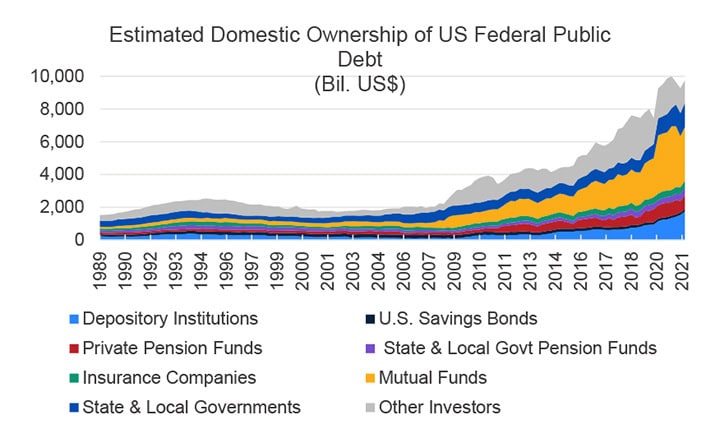

Debt can erode economic growth and sap prosperity and living standards over a period of years, demoralizing the populace and demeaning the nation in the world community. It also reduces the amount of fiscal space for supporting households and businesses during economic downturns. Public debt also diverts investment dollars away from the private sector and towards U.S. Treasury bonds, which are used to finance existing obligations of the government, not new private sector initiatives. Rising debt service costs will prevent the government from meeting the nation’s most fundamental needs. Importantly, the U.S. faces the risk of sovereign debt ratings downgrades if investors lose confidence that the government can continue to finance the debt. Lower ratings mean higher borrowing costs, and even more debt service — compounding the debt problem. Moreover, the burden of financing the debt will likely fall to domestic investors as foreign investors — notably from China and Japan — are diversifying their portfolio holdings away from U.S. Treasury securities.

Who Will Buy U.S. Debt? Domestic Investors Will Have to Carry More of the Burden

The Courage to Change What Can Be Changed

However, policymakers are not without options to address inflation, and slow, and perhaps even reverse, the trend towards sovereign debt accumulation. But the fiscal policies need to be carefully calibrated to ensure that inflation is addressed without triggering deep recessions. Spending needs to be measured, cut where possible, tightened to promote work and productivity and avoid stimulus, and paid for. And, perhaps most importantly, our nation’s leaders need to provide the political will for change. This will for change is most needed to address Social Security and Medicare which dominate the federal budget and whose Trust Funds, along with the Highway Trust Fund are going insolvent.

Most immediately, to combat inflation, Congress, the Administration, and leaders in the private sector can work together to reduce labor shortages with policies that promote work and increase participation in the labor force. Additionally, government can remove policies that disincentivize work. Supporting private/public collaboration on effective training and education programs, and expanding learn-and-earn apprenticeships (see The U.S. Labor Shortage: A Plan to Tackle the Challenge, A U.S. Workforce Training Plan for the Postpandemic Economy and Future Occupational Labor Shortages Risk Index). Increasing the EITC, reviewing and reforming occupational licensing requirements that may raise barriers to entry into a field or prevent workers from moving from state-to-state, reducing regulations (e.g., mandating truck drivers be 21 years or older), and reforming Social Security to allow older workers to work longer. Policies could also include incentivizing private sector delivery of childcare and paid family leave, actions many economists advocate that are done in other economies. The government should prioritize comprehensive immigration reform but, short of that, expand immigration by improving the H-1 visa program and increasing the number of visas issued overall.

The government can also accelerate delivery of infrastructure spending and streamline regulatory requirements to reduce the costs of poor transportation modes and energy inefficient structures over the longer haul (see Today’s Infrastructure Improvements Will Drive Tomorrow’s Economy and Building Infrastructure in Real Time: Avoiding Regulatory Paralysis). Addressing supply chain bottlenecks at ports and points of entry with improved infrastructure and technology upgrades can address parts of the problem that must be solved.

Additionally, the Administration can cut regulatory tape, reduce tariffs on imported goods, and undertake tax reform, and other rules that increase the cost of doing businesses. Particularly, tax reform would adhere to fundamental principles that tax rates should be progressive and as low as possible, consistent with revenue needs. Regarding elevated food and energy costs, the government can allow for more temporary oil and gas permitting, adopt a sensible, comprehensive energy transition plan, incentivize farmers to produce more crops, and limit the use of corn in ethanol-based gasoline production. Without actions by both the Federal Reserve and the federal government to lower inflation, the U.S. is doomed to exist in a stagflationary environment — characterized by sluggish GDP growth and prices persisting above the Fed’s 2-percent inflation target.

Pertaining to outright debt reduction, options include major reforms to entitlement programs. For Medicare and for the private health care system broadly, cost-responsible consumer choice among competing private health plans can help achieve quality, affordable care. Social Security’s costs could be reined in with gradual reductions in benefits for the most-affluent workers, and with broader coverage of the payroll tax for workers with higher wages and with generous fringe benefits that are currently not taxed. Tax policy can be reformed by removing preferential tax breaks to raise revenue in a fair and responsible manner.

Given the debt burden’s overwhelming size, it can also be addressed in segments, for example, segregating pandemic debt as a first order of priority to address. Additionally, Congress can commit to abiding by its regular budgetary process rather than resorting to stop-gap measures that may result in increases in discretionary spending and incorporating “pay fors” in its budget process. While government policymakers can do nothing to halt interest rate increases, they can help slow the accumulation of debt service by addressing the underlying debt. This can help make a bad situation from becoming worse (see Dealing With Fiscal Debt: A Policy Roadmap).

Both monetary and fiscal policy should be deployed in a consistent manner to fight inflation, and generally maintain the health of the U.S. economy. However, they should be carried out independently. In other words, the central bank — the Fed — must remain independent of government. History has shown that economies led by central banks that are influenced by short-term political concerns have performed poorly. This poor performance includes high inflation, low growth, and financial market disruption. Additionally, these negative economic conditions lead investors to lose faith in governments, resulting in sovereign debt defaults, higher interest rates, greater inflation, and less growth, needing further government support that increases debt — a vicious cycle.

During economic downturns, fiscal and monetary policies should work independently, but simultaneously to support the economy. The central bank using financial market tools that influence the degree of liquidity available, and the federal government using automatic stabilizers to support household and business balance sheets. This was evident during the worst of the covid-19 pandemic: the central bank cut interest rates to the zero-lower bound, purchased financial assets using its balance sheet, and opened a variety of liquidity and credit facilities to prevent dislocations in key financial markets; separately, the federal government provided direct stimulus to households and firms to support consumption and investment when hiring collapsed and business doors shut.

During economic expansions, fiscal and monetary policies can also support each other without erosion of independence. The central bank can manage interest rates to prevent overheating of the economy, which induces harmful levels of inflation. Separately, the federal government can reduce unnecessary expenditures on pet projects, but increase expenditures with large multipliers to support economic growth for the future. Government can also support private investment which can have even higher multipliers. The government can also reform the tax system to collect an adequate amount of revenue during goods times, but in a manner that does not overburden any one constituent. Additionally, higher tax revenues generated from a strong economy should be used for debt reduction. The Administration can also support policies and regulatory guardrails that balance safety with productivity. Additionally, the Administration can support exports by penning more free trade agreements (see A Road Map to Achieving Free but Secure Trade with Resilient Supply Chains).

A shallow, yet brief recession before end-2022 and into 2023 may be inevitable as the Federal Reserve is expected to raise interest rates rapidly and into what might be considered restrictive territory (i.e., above 3 percent) (see The Conference Board U.S. Economic Outlook). Additionally, more fiscal stimulus in the short-run — that is, spending apart from the usual automatic stabilizers that kick in during a recession — likely is not appropriate as it may fuel further inflation. However, this interlude will pass, and the federal government must focus upon fiscal sustainability and economic growth for the long haul. Assuring the achievement of these aims means addressing the root causes of outsized annual federal budget deficits and ballooning public debt — starting now.

About the Authors

Dana M. Peterson is the Chief Economist and Leader of the Economy, Strategy & Finance Center at The Conference Board. Prior to this, she served as a North America Economist and later as a Global Economist at Citi, the world’s largest investment bank. Her wealth of experience extends to the public sector, having also worked at the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C. Dana’s wide-ranging economics portfolio includes analyzing global themes having direct financial market implications, including monetary policy; inflation; labor markets; fiscal and trade policy; debt; taxation; ESG; consumption, and demographics. Her work also examines myriad US themes leveraging granular data. Peterson's research has been featured by US and international news outlets, both in print and broadcast. Publications and networks include CNBC, FOX Business, Bloomberg, Thomson-Reuters, CNN Finance, Yahoo Finance, TD Ameritrade, Barron’s, the Financial Times, and the Wall Street Journal. She is member of the Board of Directors of NBER, NABE, and the Global Interdependence Center, 1st Vice Chair of the New York Association for Business Economics (NYABE), and a member of NBEIC, the Forecasters Club, and the Council on Foreign Relations. She received an undergraduate degree in Economics from Wesleyan University and a Master of Science degree in Economics from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Dr. Lori Esposito Murray is President of the Committee for Economic Development of The Conference Board. Murray brings to CED extensive experience at the highest echelons of domestic and international policy. She most recently served as an adjunct senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations’ (CFR). Prior to her role at CFR, she held the distinguished national security chair at the U.S. Naval Academy. She also is president emeritus of the World Affairs Councils of America, the largest nonpartisan, nonprofit, grassroots organization dedicated to educating and engaging the U.S. public on global issues. Murray's work in government crosses political parties and extends to both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue. Her multiple roles have included serving as special advisor to President Clinton on the Chemical Weapons Convention and as the assistant director for multilateral affairs at the State Department’s U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. Prior to that, Murray worked as executive director of the Department of Defense’s Federal Advisory Committee on Gender-Integrated Training in the Military and Related Issues. She also headed the congressionally mandated US-China Security and Economic Review Commission, and was a consultant to President George W. Bush’s Commission on Weapons of Mass Destruction and US Intelligence Capabilities. Murray worked for almost a decade as national security advisor to Senator Nancy Landon Kassebaum (R-KS), a senior Republican member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Her responsibilities included the full spectrum of US national security: foreign policy, defense, intelligence, and trade issues. Earlier in her career, Murray served as the professional associate to the National Academy of Sciences, Committee on International Security and Arms Control. Dr. Murray received her BA from Yale University and her PhD from The Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

Expert Views

Inflation, Interest, and the National Debt

We asked experts with diverse views from across the political spectrum to share their perspectives and insights to help understand the landscape and identify solutions.