How Do the House and Senate Appropriation Bills Differ?

Last Updated September 21, 2023

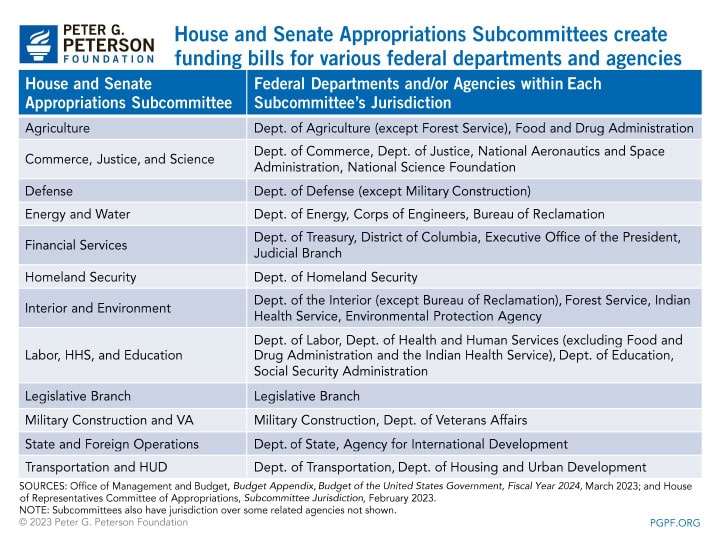

Each year, Congress must pass 12 appropriation bills that set levels of funding for various federal agencies and programs. Such funding generally covers the operations of agencies, including salaries and benefits for federal employees, grants to state and local governments, and purchases from the private sector. Appropriations are made for almost all spending on U.S. defense as well as for programs to support education, improve America’s highways, preserve national parks, and much more.

According to federal law, all 12 appropriation bills should be enacted before the start of a new fiscal year, which occurs on October 1. If the deadline is missed and a temporary provision to continue operations is not in place, the federal government will go into a full or partial shutdown (read more about that below). As lawmakers approach this year’s deadline, this piece explains the differences between House and Senate appropriations so far and what happens if all or some of the appropriation bills are not enacted by the start of the new fiscal year.

What Federal Departments and Agencies Are Included in Each Appropriation Bill?

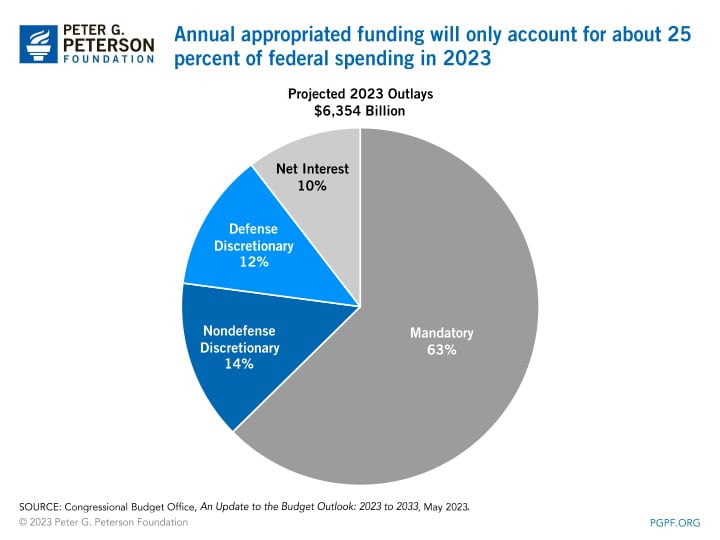

During fiscal year 2023, only about a quarter of all projected spending stems from the 12 appropriation bills that became law in December 2022. The rest (mandatory spending and net interest) is set by permanent law that is not generally revisited during the annual appropriation process.

In Congress, the appropriation process begins with the adoption of a budget resolution that sets the top-line spending level (called 302a allocations) for the upcoming fiscal year. The House and Senate Committees on Appropriations then divide that total among their 12 subcommittees (302b allocations). Guided by the 302b allocations, each subcommittee drafts its own appropriation bill. That process occurs in both the House and the Senate.

How Much Are Lawmakers Seeking to Appropriate for Fiscal Year 2024?

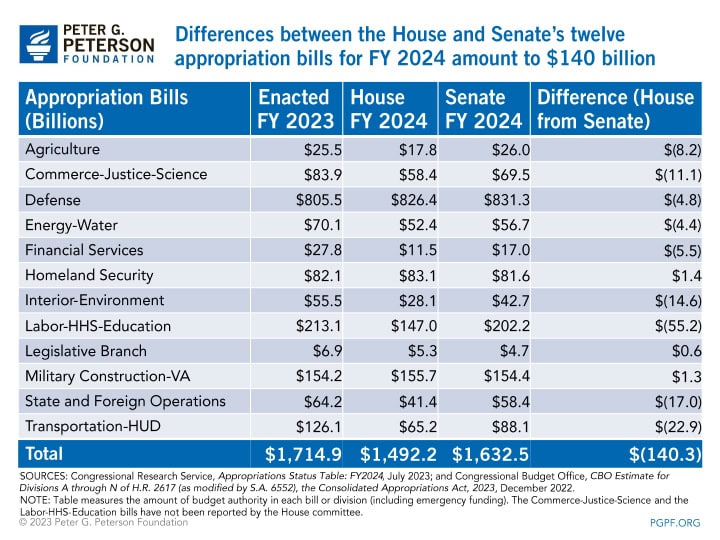

Because the House and Senate Committees on Appropriations draft separate versions of the 12 appropriation bills for each fiscal year, there are often funding differences that must be worked out between the two bodies before the bills can be brought to the President for approval. This year is no different. In total, the Senate appropriation bills currently total $140 billion more than the House bills. More than a third of that difference is in the Labor-HHS-Education bill ($55.2 billion). Generally, both chambers have appropriated less this year than levels for fiscal year 2023 because of spending limits enacted in the Fiscal Responsibility Act. The Senate appropriation bills for FY24 total five percent less than the enacted levels for FY23 while the House bills are 13 percent less. However, both chambers have appropriated more in their Defense and Military Construction-VA bills than the prior year. The House has also appropriated more funds in its Homeland Security bill than the prior year, while the Senate has done the same for its Agriculture bill.

What Happens If Congress and the President Do Not Enact the 12 Appropriation Bills?

If the House, Senate, and the President are not able to come together to enact all 12 appropriation bills for fiscal year 2024, lawmakers could enact a temporary spending bill called a continuing resolution. Continuing resolutions extend appropriations from the previous fiscal year for a specified period, giving lawmakers more time to come to an agreement on spending for the current year.

Periodically, lawmakers are unable to come to any budget agreement and fail to enact some or all of the 12 appropriation bills or a continuing resolution. In such an event, a partial or full government shutdown would occur. A full government shutdown occurs if all 12 appropriation bills are not enacted, whereas a partial government shutdown occurs when only a portion of the bills are not enacted. In that case, only the federal agencies that have not received an appropriation are affected. The most recent government shutdown (from December 2018 to January 2019) was a partial shutdown. Lawmakers must appropriate funds because federal agencies require appropriations from Congress to spend or obligate money under federal law. Historically, government shutdowns have been costly, bad for the economy, and interrupted federal programs and services.

Conclusion

The 12 annual appropriation bills are a key part of the annual budget process that lawmakers must enact to keep the government functioning regularly. Currently, the House and Senate appropriation bills have significant funding disparities that must be resolved. A majority of Americans agree that a government shutdown distracts from the county’s fiscal challenges, and 90 percent of voters want lawmakers to work together to avoid a shutdown. Enacting all 12 appropriation bills on time and through regular order is an important part of responsible, forward-looking policymaking.

Image credit: Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images

Further Reading

How Much Can the Administration Really Save by Cutting Down on Improper Payments?

Cutting down on improper payments could increase program efficiency, bolster Americans’ confidence in their government, and safeguard taxpayer dollars.

How Do Quantitative Easing and Tightening Affect the Federal Budget?

The Federal Reserve plays an important role in stabilizing the country’s economy.

Here’s How No Tax on Overtime Would Affect Federal Revenues and Tax Fairness

Excluding overtime pay from federal taxes would meaningfully worsen the fiscal outlook, while most of the tax benefits would go to the top 20% of taxpayers.