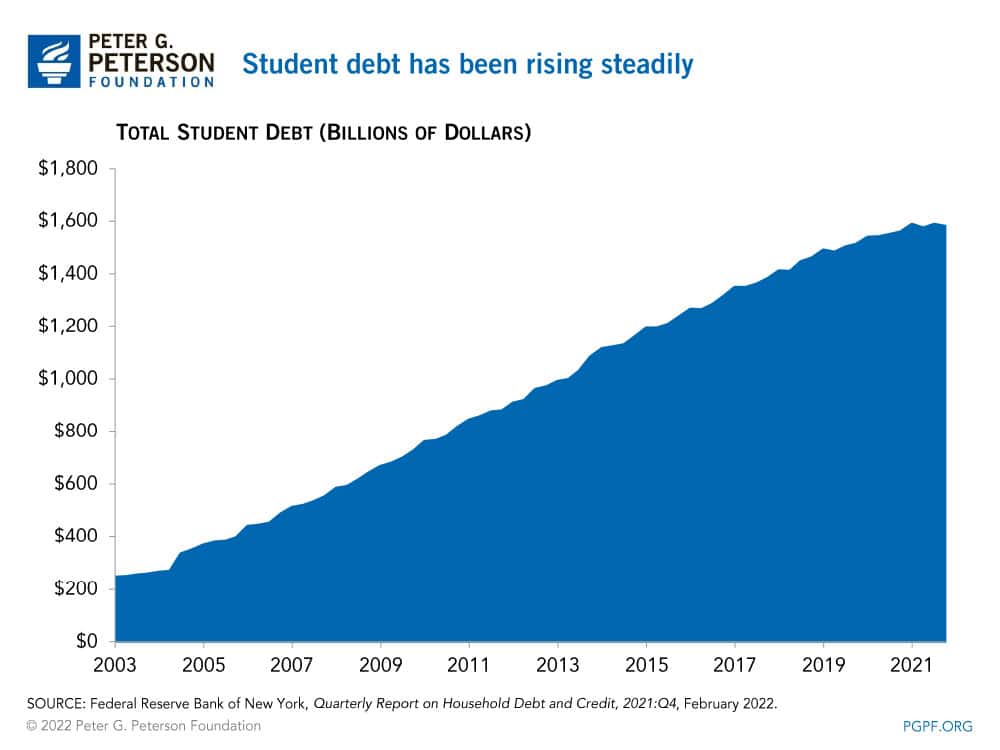

Skyrocketing student debt has generated significant discussion about ways to improve the financing of higher education in the United States, including proposals for debt forgiveness and other reforms. A key part of understanding the complex dynamics at play is unpacking the federal government’s role as a direct lender; how that role has evolved over time; and its effect on student aid, government costs, borrower experience, and the nation’s finances.

For more than 60 years, the federal government has played a major and growing role in helping students finance higher education by extending access to credit through loans and loan guarantee programs. Over time, federal policy changes have expanded the government’s role, enabling greater administrative flexibility and improved access to more favorable loan programs at a potentially lower cost to the borrower. However, those enhancements have also led to rapidly rising student debt, which can have costly implications for the federal budget and place serious economic burdens on borrowers.

The Evolution of Federal Student Loan Programs

The first federal student loans were issued directly to borrowers under the National Defense Education Act of 1958 to help ensure the availability of highly trained Americans in scientific and technical fields. Since then, federal student loan programs have been significantly restructured twice.

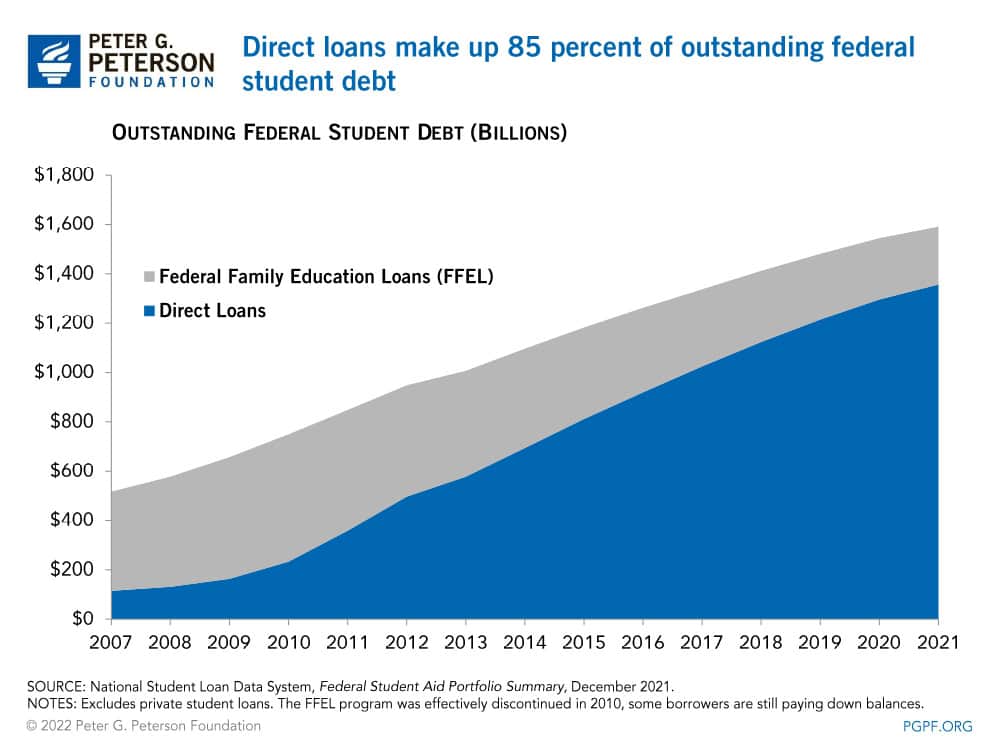

First, in 1965, the federal government began subsidizing and guaranteeing student loans issued by private lenders through the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) program. Through FFEL, lenders received federal subsidies to extend low-interest loans, with the government agreeing to cover most losses if the student defaulted on the loan. Then, in 1972, lawmakers established the government-sponsored enterprise Student Loan Marketing Association (Sallie Mae) to facilitate liquidity in the loan market. Sallie Mae originated federally guaranteed student loans under FFEL and worked as a servicer and collector of federal student loans.

Research on the cost of federal loans suggested that issuing loans directly to borrowers would be more cost effective than loan guarantees, prompting lawmakers to pilot a direct student loan program in 1992 as part of a plan for deficit reduction. Implementing a direct student loan program would eliminate the “middleman” of FFEL lenders and related subsidies. Both guaranteed and direct student loan programs operated in parallel until 2010, when the FFEL program was ended for new loans. At that time — all else equal — the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that switching to direct lending would save $62 billion over the next 10 years.

Another impetus for the transition to direct lending by the federal government was a concern that students had limited borrowing opportunities due to tightening credit markets around the time of the Great Recession. For example, the number of FFEL lenders declined by 65 percent between 2008 and 2009 as they cited insufficient capital to issue loans. Many analysts and policymakers contended that switching entirely to direct lending by the government would ensure that the supply of credit for student loans would not be at risk during future recessions because of the program’s use of federal funds.

What Was the Result of Implementing Direct Lending by the Federal Government?

The federal government’s switch to direct lending had various implications on demand for federal student aid, government costs, borrower experience, and administrative flexibility.

Increased Demand for Student Aid

Increased demand for student aid was likely not a result of greater access to credit from the switch to direct lending. According to the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC), there is no evidence that borrowers lacked access to FFEL lenders during the Great Recession despite the reduction in the number of participating institutions because the Department of Education purchased loans to enable private lenders to continue offering credit. However, the switch to direct lending did create access to more favorable terms for borrowers and expanded loan forgiveness and repayment programs, which may have incentivized individuals to borrow, or to borrow more, than they otherwise would have.

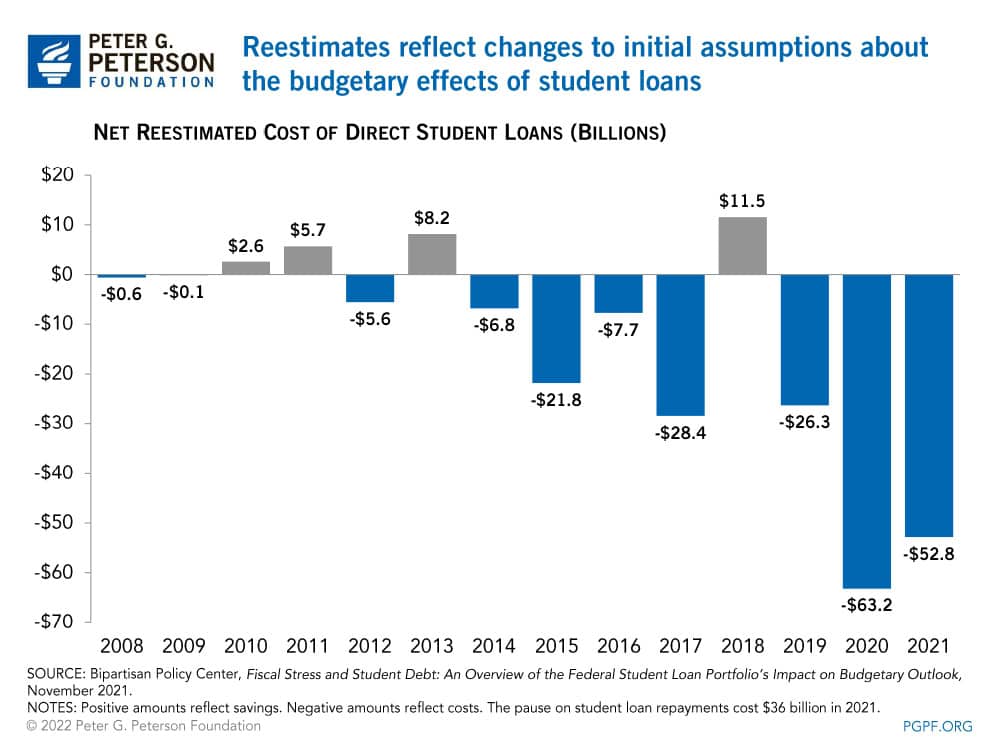

Greater Costs to the Federal Government

The switch to direct lending was expected to produce budgetary savings, but falling rates of repayment due to student loan forgiveness and income-driven repayment programs have contributed to greater-than-anticipated costs to the government. For example, credit reestimates in the first decade after the switch to direct lending (2010–2019), show that student loans generated higher costs than CBO originally anticipated. The Administration produces reestimates annually to account for changes in assumptions about interest rates, repayments, and other factors as well as actual experience with loan cohorts.

Under direct lending, CBO initially projected that new loans would produce 9 cents in savings for every dollar lent over the program’s first decade. Instead, reestimates show that such loans have cost the government 8 cents for every dollar on average, according to BPC. That said, it is unknown whether direct loans have been more or less expensive than FFEL loans would have been.

Streamlined Process

Direct lending improved the borrower experience by streamlining the application process. For example, the switch eliminated the need to interact with a private lender after the government approved a borrower, easing the burden on students looking to finance their education. While the borrower experience improved, some argue that loan counseling provided by the Department of Education has been less effective than the counseling provided by private lenders and may result in some borrowers misunderstanding the financial obligation they are assuming.

Relief Options

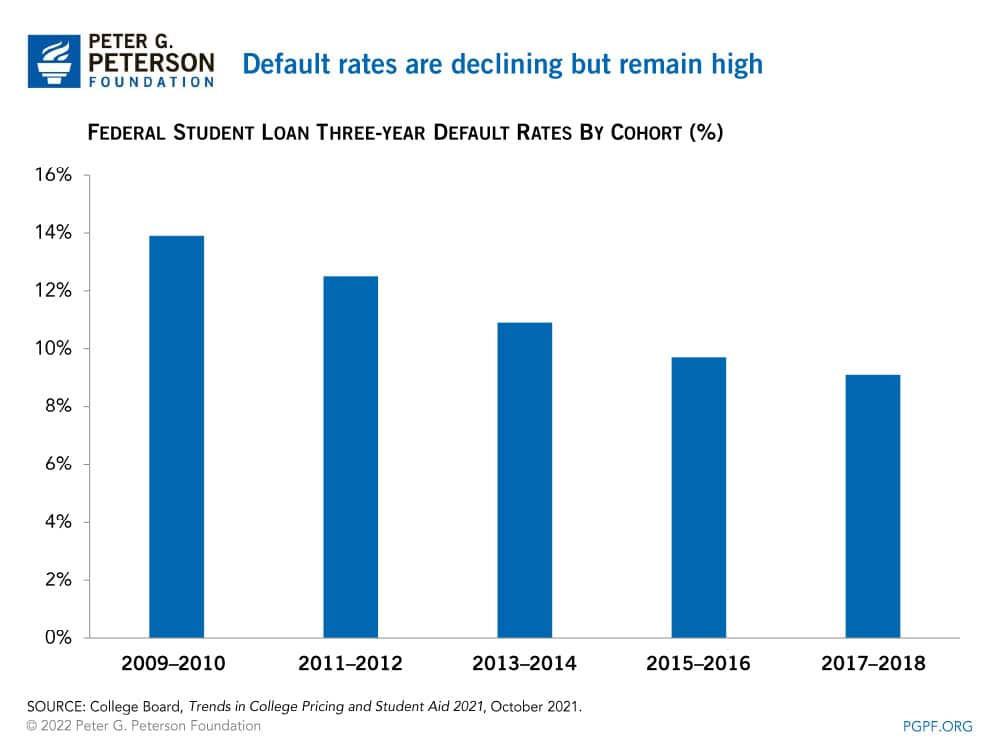

Direct lending gave the government greater flexibility to provide relief to borrowers and has contributed to a decline in default rates, although such rates remain high. As an example of relief efforts, during the pandemic, the government paused interest and payments on federal student loans through August 2022; however, most FFEL loans do not qualify for such relief.

Looking Ahead

Direct lending has allowed the government the flexibility to expand access to student loans and relief initiatives. However, evidence shows that the switch has not yielded the savings initially projected. At the same time, student debt continues to grow and burden millions of Americans. As policymakers consider ideas to reform the student loan program, proposals should effectively target relief and account for increased burdens on the federal budget and taxpayers.

Image credit: Mario Tama/Getty Images

Further Reading

How Do Quantitative Easing and Tightening Affect the Federal Budget?

The Federal Reserve plays an important role in stabilizing the country’s economy.

How Do Federal Student Loans Affect the National Debt?

Student debt held has been steadily increasing ever since the federal government switched to direct lending.

How Does Climate Change Affect the Federal Budget?

Climate change and its effects already impose a cost on the American economy and the federal budget.