Interest Costs on the National Debt Set to Reach Historic Highs in the Next Decade

Last Updated May 31, 2022

Interest payments on the national debt are on the rise. Driven by rising interest rates and the accumulation of federal debt, interest will nearly triple in the next 10 years and reach a historic high relative to the size of the economy by 2032. That rapid growth is outlined in the latest report from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and is a clear sign of the threat that America’s fiscal imbalance poses to the country’s economic future. Rising debt, fueled by mounting interest costs, can restrain the economy by crowding out private investment, enhancing the risk of a fiscal crisis, and contributing to other potential economic effects. Rapid growth in interest payments on debt can crowd out important priorities within the budget and lead to a vicious circle of even more debt, deficits, and interest payments in the future.

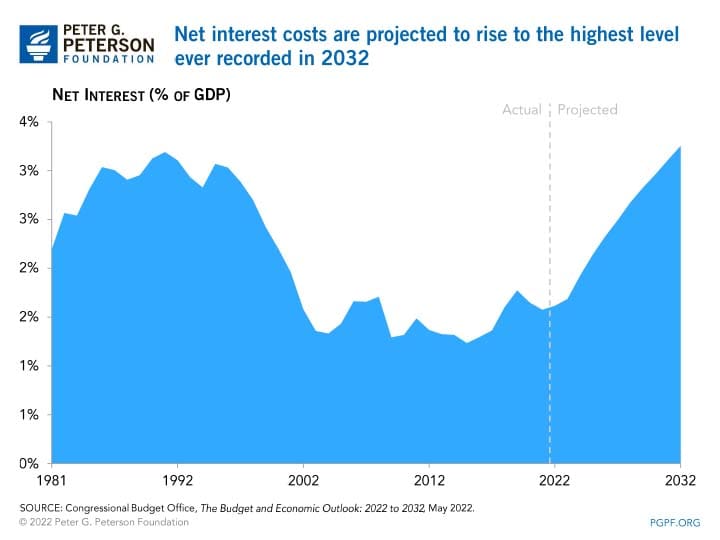

Interest Costs Will Reach Historic Highs Within the Next 10 Years

CBO projects that annual interest costs will rise from $399 billion in 2022 to $1.2 trillion in 2032. As a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), those costs would double from 1.6 percent of GDP in 2022 to 3.3 percent in 2032, which would be the highest level ever recorded.

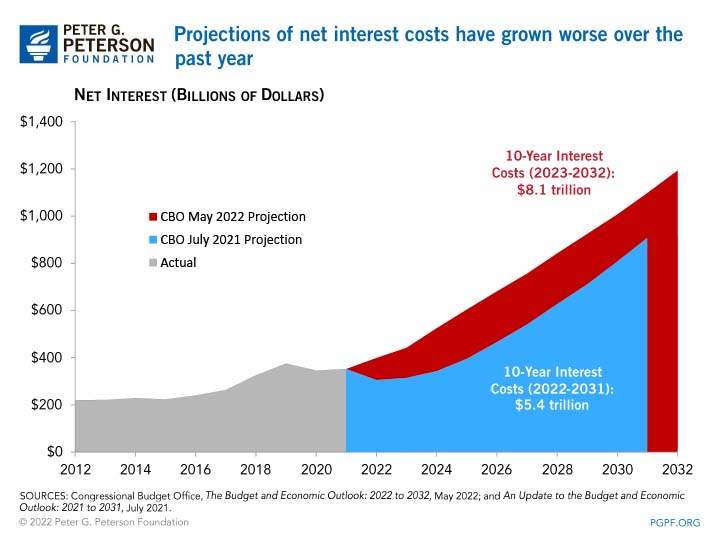

Interest costs are now projected to be significantly higher than CBO calculated nearly a year ago. Over the 2022-2031 period that CBO reported on last year, the agency projected that interest costs would total $5.4 trillion; rapid inflation and higher interest rates have boosted that projection by $1.9 trillion, or 35 percent. Over the current 10-year period from 2023 to 2032, interest costs would total $8.1 trillion.

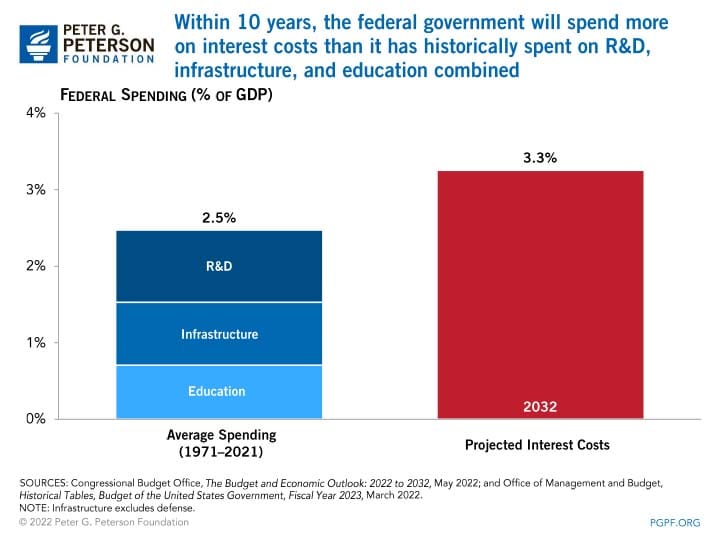

To contextualize how large interest costs would be at the end of the current projection period, consider that such costs would represent 13 percent of all spending in the budget in 2032. That’s up significantly from 7 percent in 2022, and we would actually be spending nearly $200 billion, or 20 percent, more on interest than on national defense.

Accruing debt and paying interest over time would be more justifiable if the borrowing had been used to make investments. However, very little of the federal budget is allocated to investments such as spending on education, infrastructure, and research and development. In fact, if current policies stay in place, interest costs would exceed what the federal government has historically spent on key investments within the next decade.

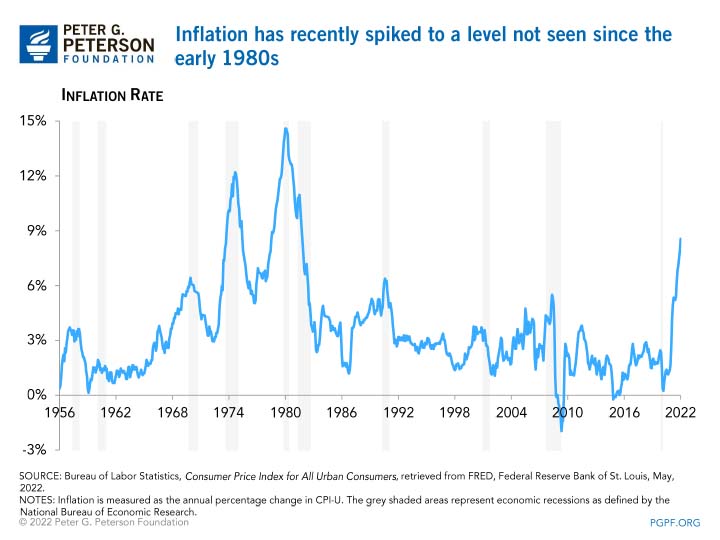

Interest Rates and Inflation Will Drive Interest Costs on the National Debt

Rising interest rates and high inflation are key drivers in the growth of the nation’s interest costs. For example, interest costs will total nearly $400 billion in 2022 alone, a 13 percent increase from last fiscal year, largely due to higher levels of inflation, which boost the face value of certain Treasury securities. While inflation has been relatively low over the past few decades, it spiked to 4.7 percent in 2021 — a level that had not been seen since the early 1980s — primarily due to disruptions in the nation’s supply chain, the war in Ukraine, and the federal support provided in response to the pandemic.

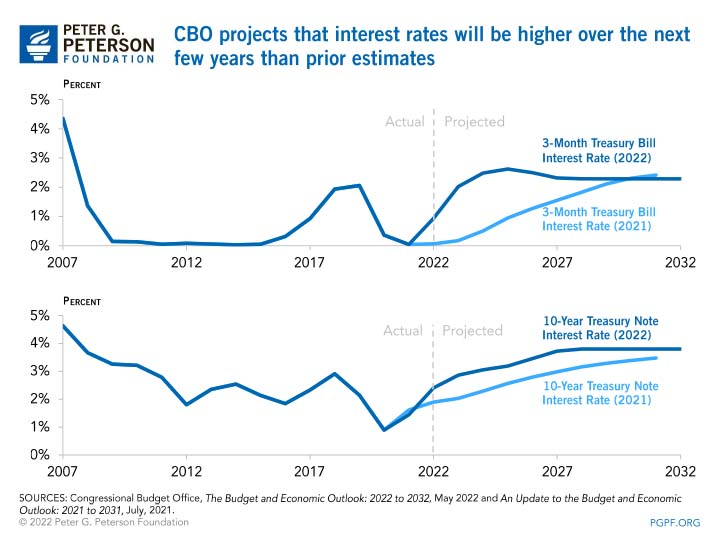

The rise in interest costs throughout the rest of the projection period is largely due to rising interest rates on U.S. Treasury securities. According to CBO’s projections, short-term interest rates are projected to climb from 0.5 percent at the end of last year to 2.6 percent at the end of 2025, before falling to around 2.3 percent through 2032. Interest rates on long-term securities are also projected to grow, rising from 1.5 percent at the end of 2021 to 3.8 percent in 2028, where they are expected to remain through the remainder of the projection period.

Those rates are projected to climb for a number of reasons. Short-term rates are projected to rise in concert with the federal funds rate, a monetary policy tool used by the Federal Reserve to contain rising prices. The Federal Reserve has raised the target for the federal funds rate twice in the past couple of months, from near zero to between 0.75 and 1.00 percent, and CBO projects they will raise it further in the coming years, with a peak of around 2.6 percent.

Expectations about short-term rates can also influence long-term interest rates. In addition, the Federal Reserve plans to reduce their holdings of Treasury securities, which would increase pressure on long-term rates. Furthermore, CBO anticipates an increase in the term premium for such securities (the additional return paid to holders for the extra risk incurred in holding longer-term notes and bonds), which was low in the years preceding the pandemic due to relatively weak economic growth and a heightened demand for longer-term securities.

CBO’s latest projections of interest rates and inflation are higher than the agency reported in July 2021, contributing to a worse fiscal outlook relative to the projections from last year. Last year, before high levels of inflation were realized, the agency projected that such price changes would remain between 2.3 and 2.5 percent over the 2022–2031 period; their current projections, by comparison, show inflation averaging 6.1 percent in 2022 before falling back to that range by 2024. CBO’s projections for both short-term and long-term rates are also higher, on average, relative to last summer’s report. The increase in projections of interest rates are mostly the result of higher inflation and the accelerated actions by the Federal Reserve to raise the fed funds rate.

Interest Costs Will Eventually Become the Largest “Program” in the Federal Budget

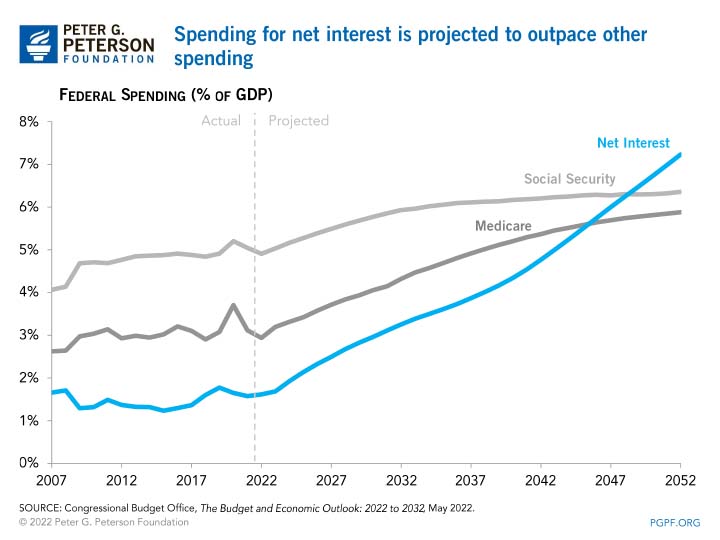

The growth in interest costs presents a significant challenge in the long term as well. Interest costs on the national debt are projected to total around $66 trillion over the next 30 years and would become the largest “program” in the federal budget within that period — surpassing Medicare in 2046 and Social Security in 2049.

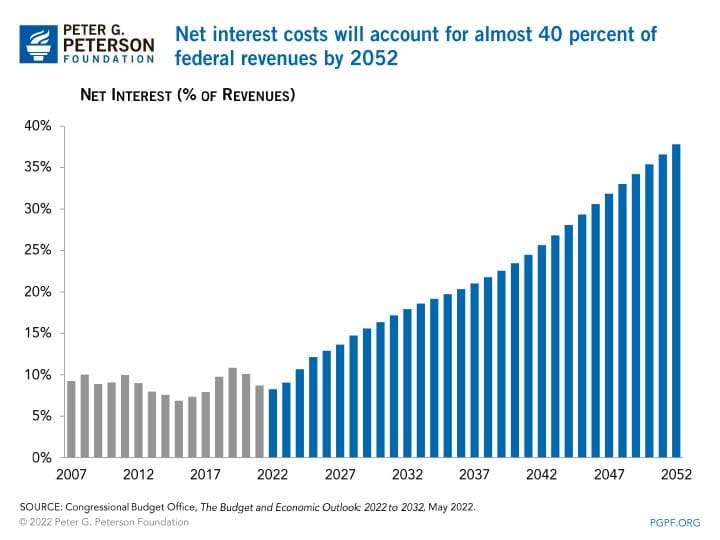

As such costs rise, they’ll take up a growing share of the nation’s revenues. By 2052, interest costs will account for almost 40 percent of federal revenues. Those levels would greatly exceed the previous high of 19 percent.

Growth in interest costs in the long term would be driven by an accumulation of federal debt, which is expected to nearly double from 98 percent of GDP in 2022 to 185 percent in 2052, and a sustained, gradual increase in interest rates. Interest rates may remain relatively high, compared to the past several years, in the long run due to a reduction in the Federal Reserve’s holdings of Treasury securities and the continued buildup of the national debt. The escalation in debt puts upward pressure on interest rates and therefore increases interest costs, which in turn further boosts deficits and debt and continues that cycle.

Why Interest Costs Matter for the Nation

The long-term fiscal challenges facing the United States are serious. As interest costs rise and the nation’s debt grows, the country’s fiscal position will be especially vulnerable to rising interest rates. The additional borrowing costs incurred by increases in interest rates will be greater when debt is high compared to when debt is low. Furthermore, ballooning interest costs threaten to crowd out important public investments that can fuel economic growth in the future.

Rising interest costs also greatly contribute to the nation’s large deficits and fuel the nation’s rising debt. As interest rates and costs rise, we are seeing the unfortunate consequences of our unsustainable fiscal outlook. It is vital for lawmakers to take action on the growing debt to ensure our nation provides a stable economic future for all Americans.

Related: Do Higher Interest Rates Make a Debt Crisis More Likely?

Image credit: Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Further Reading

National Debt Could More than Double the Size of the Economy

GAO’s findings add to a chorus of nonpartisan evidence and analysis showing that action is needed to improve our fiscal outlook.

Long-Term Budget Outlook Leaves No Room for Costly Legislation

As lawmakers consider costly legislation to extend expiring tax provisions this year, CBO’s latest projections serve as a warning that our fiscal outlook is already dangerously unsustainable.

Moody’s Warns Recent Policy Decisions Worsen U.S. Fiscal State, Maintains Negative Outlook Rating

Moody’s says that the United States is in fiscal deterioration, warning that government policy decisions in the near term could contribute to higher interest rates and worsening national debt.