This is the second entry in our new six-part series exploring the effectiveness of the fiscal response to the coronavirus pandemic. To receive updates on new pieces as they are published, sign up for our email newsletter.

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic led to record levels of unemployment and lost income for millions of Americans. In response, policymakers created new safety net programs and expanded existing ones to provide support to those in need. Such programs have been a key component to the U.S. response to the public health crisis — they have not only protected vulnerable populations from poverty, but have also helped mitigate the economic downturn. In this blog, the second in our series on the effectiveness of the nation’s fiscal response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we evaluate how safety net programs have boosted the economy and assisted individuals and families during the pandemic.

Unemployment Insurance

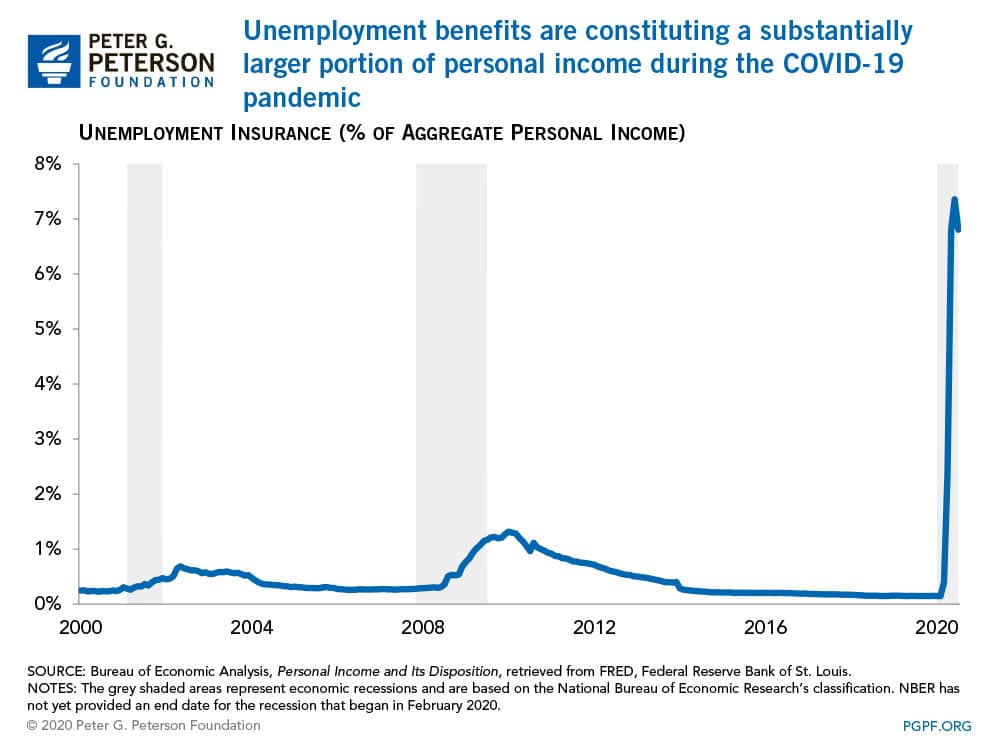

Unemployment Insurance is a longstanding, joint federal-state program that provides temporary cash benefits to those who have recently been laid off. Benefit levels vary by state and are based on a percentage of one’s earnings; payments can last up to 26 weeks. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers expanded the program by boosting benefits by up to $600 per week (a provision that expired in July), extending benefits by 13 weeks, and expanding eligibility requirements to include more categories of workers. As a result of the rapid increase in those claiming unemployment and the effect of the new programs, spending on unemployment compensation has skyrocketed to a monthly average of $84 billion from April to August — more than 18 times larger than the amount spent in March. Many analysts contend that the expansion of such benefits has been one of the most effective components of the government’s fiscal response to the pandemic.

Enhanced Unemployment Benefits Have Helped Boost the Economy

According to the Peterson Institute of International Economics, increased spending on unemployment compensation played a crucial role in supporting workers who lost their jobs. In July 2020, unemployment insurance accounted for 7 percent of aggregate personal income, significantly higher than the previous high of 1.3 percent in the aftermath of the financial crisis a decade ago.

Looking ahead, the growth in consumption as a result of enhanced unemployment benefits is projected to provide a boost to the economy in the near future. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the program will increase economic output by $301 billion through 2023. Over the same time period, it is expected to cost $442 billion — meaning the program will boost the economy by 68 cents for every dollar of budgetary cost.

Do Unemployment Benefits Inhibit Supply of Labor?

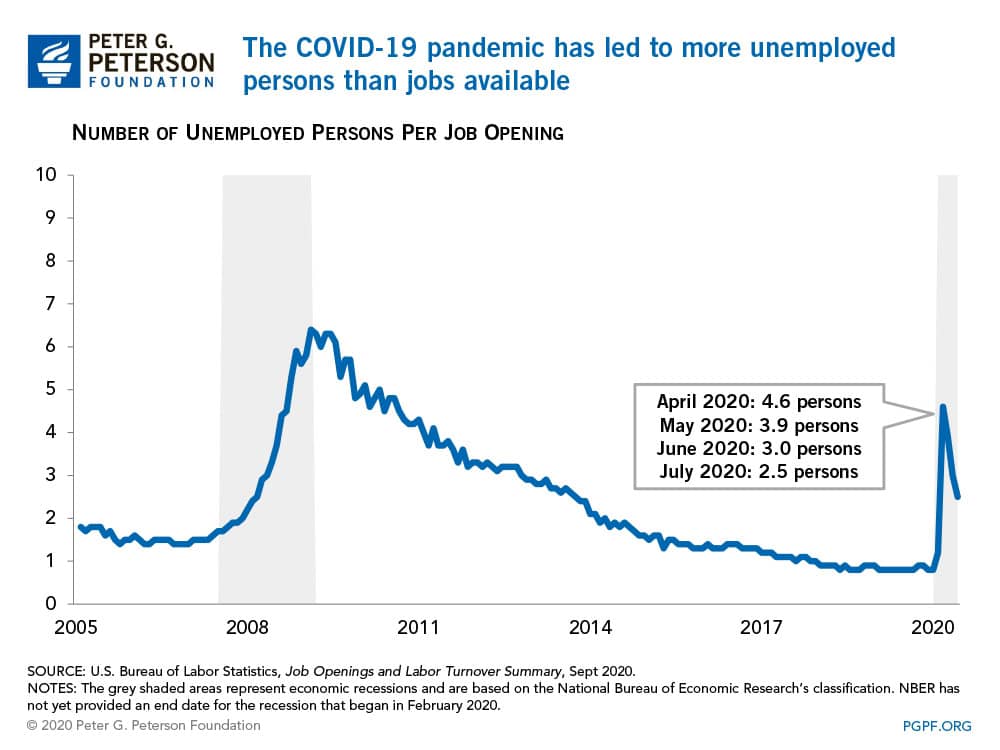

Increases in unemployment benefits have frequently been criticized for their potential negative impact on the labor supply by discouraging work. However, CBO reports that the effect is smaller during the ongoing public health emergency than under normal times because unemployment is being driven primarily by the closure of businesses and the lack of employers hiring, and less by the effects of the benefits on the recipients’ willingness to work. From April to July, there were about 19.5 million people unemployed per month on average, but only 5.7 million monthly job openings; in other words, there have been about 3.4 people unemployed for every open job.

Extended unemployment benefits can also have macroeconomic benefits; according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, those benefits can improve the functioning of the labor market as well as economic productivity as they allow unemployed individuals more time to find a job better suited to their skills.

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the largest federal program aimed at combating hunger and food insecurity among low-income Americans. While SNAP is designed to cover more people during economic downturns, the federal government further enhanced the program by expanding benefits to more children, allowing states to issue additional benefits up to the maximum amount, and suspending work requirements for the program. As a result, federal spending on SNAP has risen to an average of $9 billion per month since April, which is nearly double the amount spent before the pandemic. Additionally, the expansions to the program are projected to increase program costs by $66 billion through 2023. During the pandemic, the program has provided support to millions of Americans and helped alleviate the effects of the economic downturn; however, many argue that the legislation that expanded the program did not do enough to help the neediest.

How Has SNAP Affected the U.S. Economic Outlook?

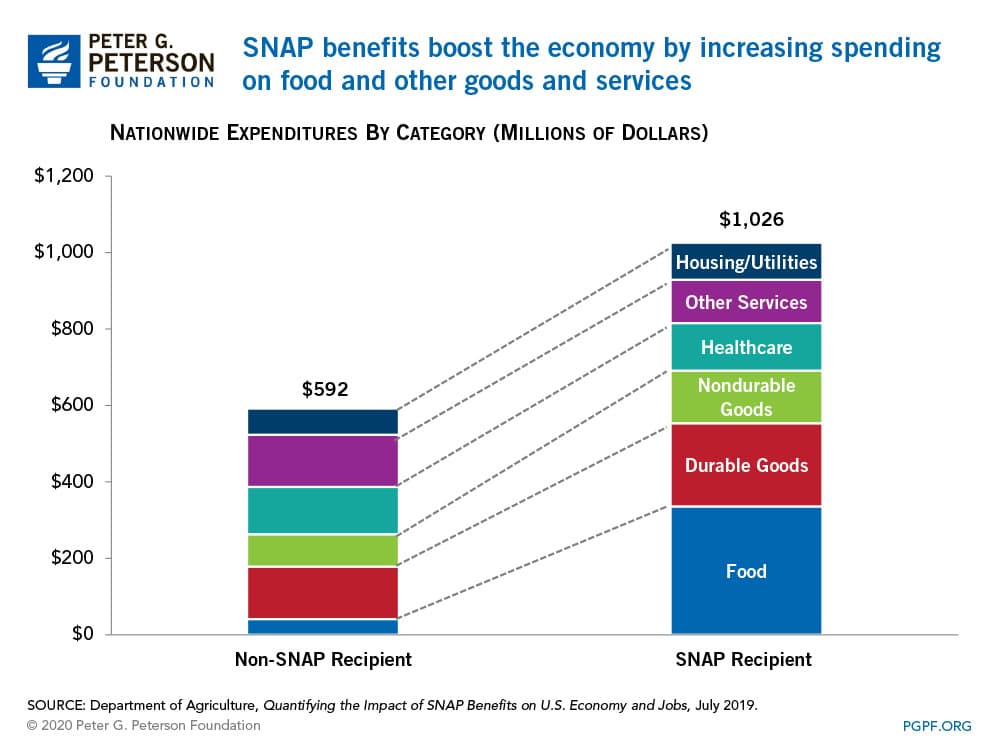

Enhanced spending on SNAP, in addition to unemployment benefits, will provide the most meaningful boost to U.S. GDP in the short-term according to Moody’s Analytics chief economist Mark Zandi and Harvard economics professor Raj Chetty. During economic downturns, the program has been found to increase economic output by as much as $1.54 for every dollar of benefits. In addition, SNAP provides a quick injection of cash into the economy; according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, about 80 percent of all benefits are redeemed within two weeks of receipt and 97 percent are spent within a month.

How Has SNAP Assisted Low-Income Americans During the Pandemic?

SNAP has historically demonstrated its effectiveness in helping low-income Americans afford food — decreasing the likelihood of such individuals being food insecure by as much as 30 percent. Additionally, by providing nutritional assistance and freeing up financial resources for recipient families, the program reduces poverty; in 2018 (the latest year for which data is available), SNAP lifted 3.2 million people out of poverty. Since February of this year, more than 6 million new people have joined the program — showing the rapid increase in the program’s reach during the ongoing recession.

While there is a general consensus that the program is effective in achieving its goals, several studies point out that the pandemic presented unique challenges that inhibited the program’s effectiveness. An article in the Journal of Urban Health reports that the closure of businesses and social distancing measures have upended the shopping strategies that low-income people use to acquire the most affordable products, such as visiting multiple stores. In addition, food hoarding during the early stages of the pandemic placed SNAP recipients at an extreme disadvantage. Likely due to those factors, SNAP’s effects on reducing food insecurity have been lower than expected during the COVID-19 crisis. While food insecurity among families with children rose to 25 percent when the pandemic started, enhanced SNAP benefits and other transfer programs only reduced that number by 3 percentage points as of May. More recent survey results from the Census Bureau suggest that food insecurity has remained well above pre-pandemic levels through mid-September.

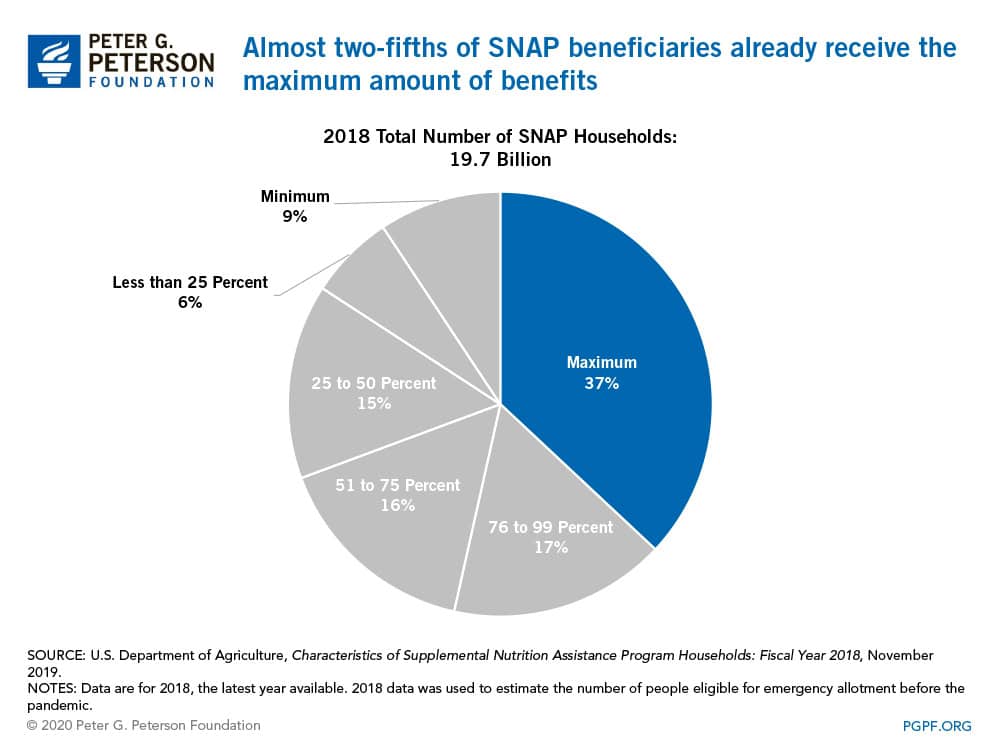

In addition, analysts from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities contend that the recent expansion of the program excluded many low-income Americans in need. Through “emergency allotments,” SNAP beneficiaries were able to receive the maximum amount of benefits for their household size. However, 7.3 million low-income households — who account for nearly two-fifths of the entire SNAP population — were already receiving maximum benefits and were therefore not eligible for any additional aid from the program when the pandemic began. As such, analysts suggest that lawmakers should enhance benefits for those recipients to better capitalize on the program’s effectiveness.

Medicaid

Medicaid, a joint federal-state program that provides healthcare coverage primarily for low-income individuals, has also played a significant role during the pandemic. In March, the program was expanded to provide coverage for COVID-19 tests and to enable states to cover the costs of the tests for individuals not originally eligible for Medicaid. In addition, legislation raised the federal share of program costs, increasing financial assistance to states. During the pandemic, monthly federal outlays on the program averaged $42 billion — more than 20 percent higher than the average monthly outlays in 2019. Pandemic-related provisions that expanded the program are expected to cost $132 billion over the next three years. Medicaid has helped many Americans gain health coverage during the pandemic; however, without additional support from the federal government, the rising participation in the program may place significant strains on state budgets.

Medicaid Has Increased Access to Healthcare during the Pandemic

The massive spike in unemployment following the COVID-19 outbreak has caused many Americans to lose their employer-sponsored health insurance. Though estimates vary, one study found that as many as 27 million workers (and their spouses and dependents) have lost such coverage over the first two months of the pandemic. However, the majority of those individuals are now eligible for coverage through Medicaid. Between February and June, the latest months for which federal data is available, all but one state saw growth in the program’s enrollment — with some as high as 13 percent.

That increase in participation was driven largely by the increase in the number of people that saw their income reduced and therefore became eligible for coverage. In addition, the legislation that expanded the program requires that for states to receive federal funding for Medicaid, they must continue coverage for current enrollees and cannot pass new eligibility requirements — causing fewer people to disenroll.

Many studies also found that the rise in Medicaid participation following the pandemic was more significant for states that accepted Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. Such trends raise health concerns particularly for non-expansion states because those without insurance may be prone to forgo tests and treatments because of the costs of receiving medical care.

How Has Medicaid Affected State Budgets?

One of the largest concerns regarding Medicaid is its impact on state budgets, which have been strained by lower tax revenues and increased spending due to the response to COVID-19. Medicaid was already the largest expenditure for states prior to the pandemic, and with enrollment rising, states are expected to face further increases in program costs. The increase in the federal share of the program’s costs will only partially alleviate that burden.

Other Safety Net Programs Played an Important Role

In addition to the three major safety net programs discussed above, lawmakers enacted a number of new provisions that provide income support during the pandemic. Those include $4 billion in grants for those who are homeless or are at risk of homelessness, $3.5 billion for childcare assistance for essential workers, and $3 billion in rental assistance. Many existing programs have also undergone temporary changes, such as the suspension of student loan payments, deferment of federal tax payments, and eased requirements for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. All of those provisions have played a critical role in mitigating the impact of the pandemic for many Americans.

Conclusion

Safety net programs have played a major role in the pandemic response and have been effective in financially assisting millions of Americans and in helping the economy recover. However, several studies suggest that further expansions or continuations of those enhanced programs may be needed to provide sufficient assistance as the economy remains slow in the near term. Lawmakers should learn from the safety net programs’ successes and challenges during the pandemic and continue to provide the necessary support while amending the programs’ weaker points.

Photo by Michael Loccisano/Getty Images for Food Bank For New York City

Further Reading

7 Key Trends in Poverty in the United States

Thirteen percent of the U.S. population lives in poverty. Learn more about the demographic and regional variations in the poverty rate.

What Is SNAP? An Overview of the Largest Federal Anti-Hunger Program

SNAP is the largest federal program aimed at combating hunger and food insecurity among low-income Americans.

Chart Pack: Social Programs

A selection of charts about crucial social programs (Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and SNAP), their financial outlook, and place within the federal budget.