How Has the Coronavirus Pandemic Affected Federal Spending on SNAP?

Last Updated March 23, 2021

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has led to a massive reduction of economic activity in the United States. Millions of Americans are out of work and are relying on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, sometimes referred to as Food Stamps), a key part of the social safety net that provides benefits to help those with low or reduced incomes buy food.

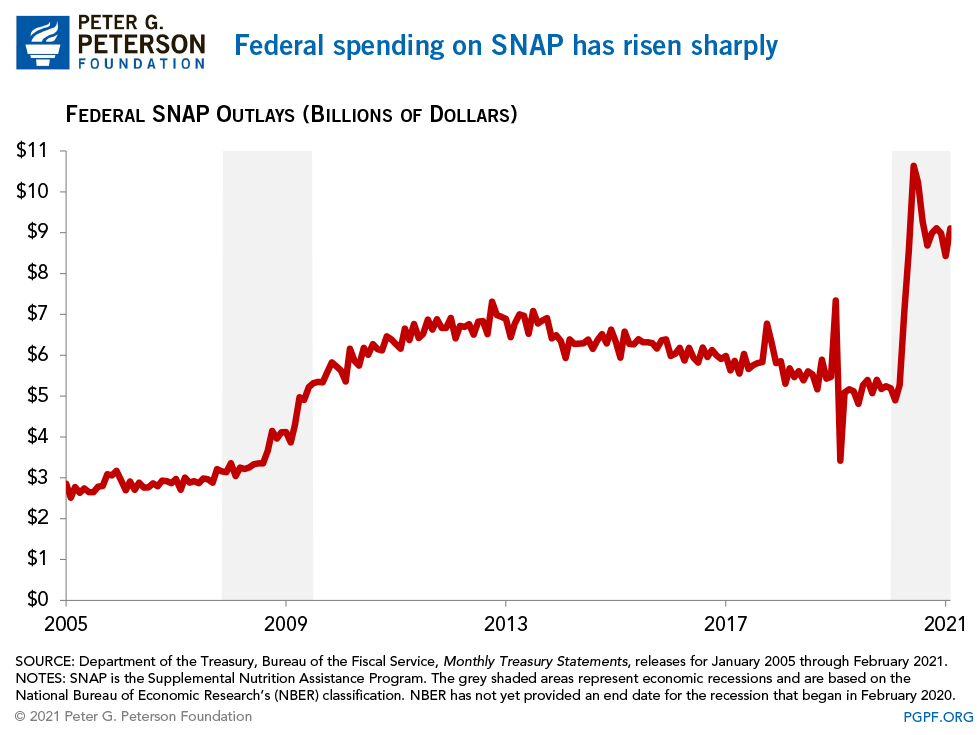

Since April 2020, the federal government has spent an average of $9 billion per month on SNAP — 71 percent higher than the amount spent in March 2020 (before the pandemic was widely recognized). Federal spending on the program increased significantly following the outbreak of COVID-19; from March/April to June, outlays grew at an average of 26 percent per month — nearly double the largest monthly growth seen during the Great Recession. The only time when spending on the program has grown nearly as fast was around February 2019, when benefits for that month were advanced to prepare for a government shutdown.

SNAP is an automatic stabilizer — participation in the program naturally increases when the economy slows. Such was the case during the Great Recession, when participation grew about 20 percent, reflecting large numbers of Americans without adequate access to food.1 Today, a similar situation exists because of the COVID-19 pandemic, as significant income loss has made more people eligible for benefits. As of November 2020, the latest month for which data are available, participation was 11 percent higher than in March of that year.

As noted above, in addition to the countercyclical nature of SNAP, the growth in spending also results from legislative changes to the program. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA), which was signed into law on March 18, 2020, included provisions that expanded SNAP benefits for new and existing recipients during the ongoing public health emergency. Those provisions have been continued and further expanded through the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 and the American Rescue Plan, as well as through executive action by the Biden administration. Key changes to the program include:

- The Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT): Through P-EBT, states are allowed to provide benefits to families with children that rely on free or reduced-price school meals.

- Emergency Allotments and Increase in Maximum Benefits: States can provide additional benefits by issuing emergency allotments to families. The Biden Administration has also issued an executive order for the Agriculture Department to consider providing emergency benefits to low-income families who were already receiving the maximum amount. In addition to the emergency allotments, the maximum benefit level has been increased by 15 percent through September.

- Suspension of work requirements: The FFRCA temporarily suspended the three-month work and work training requirements for able-bodied adults. In December 2020, legislation also waived work requirements for low-income college students.

SNAP comprises a relatively small portion of the federal budget, but it is the largest program addressing food security on the federal level. The increase in spending on the program is therefore critical in providing assistance to families during the pandemic.

1. In 2010, 14.5 percent of American households were food insecure at one point — which means that they did not have access to sufficient food due to lack of financial resources.

Image credit: Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Further Reading

A Bipartisan Roadmap for Social Security Reform

Lawmakers are running out of time before automatic reductions to benefits are activated; the Brookings Institution plan is a valuable contribution to the policy discussion.

U.S. Population Growth Is Slowing Down — Here’s What That Means for the Federal Budget

Understanding how demographic challenges contribute to the United States’ fiscal challenges can help policymakers adopt fiscally sustainable policies.

What Is the Farm Bill, and Why Does It Matter for the Federal Budget?

The Farm Bill provides an opportunity for policymakers to comprehensively address agricultural, food, conservation, and other issues.