Pandemic Budget Crunch Could Force States to Slash Social Services, Education, Police Budgets, More

Last Updated July 1, 2020

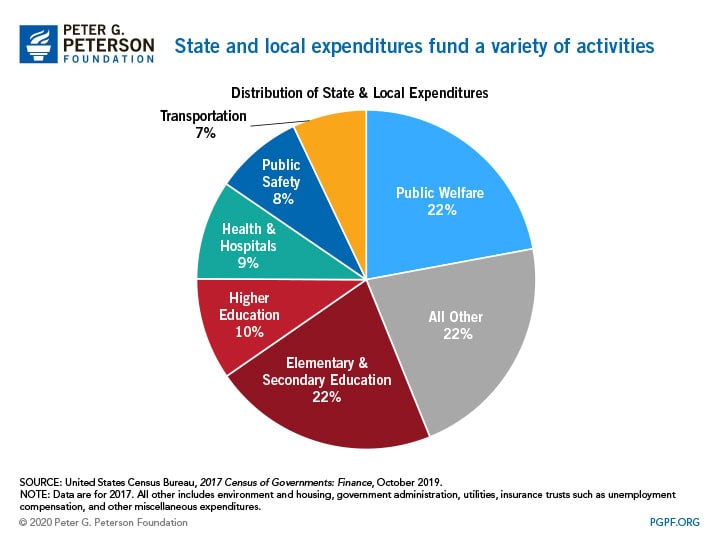

State and local governments fund many of the services that Americans come into contact with on a daily basis, including education, healthcare, infrastructure, income support programs, and police departments. However, governors, state budget officers, and economists are warning that state budgets have been severely impacted by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Without federal intervention, many services could be drastically reduced to meet balanced budget requirements. Below we review how the pandemic is affecting state finances, preliminary measures that states are taking to respond to this pressure, and the longer-term impacts of this funding crisis.

State and Local Governments are Facing a Budget Crunch

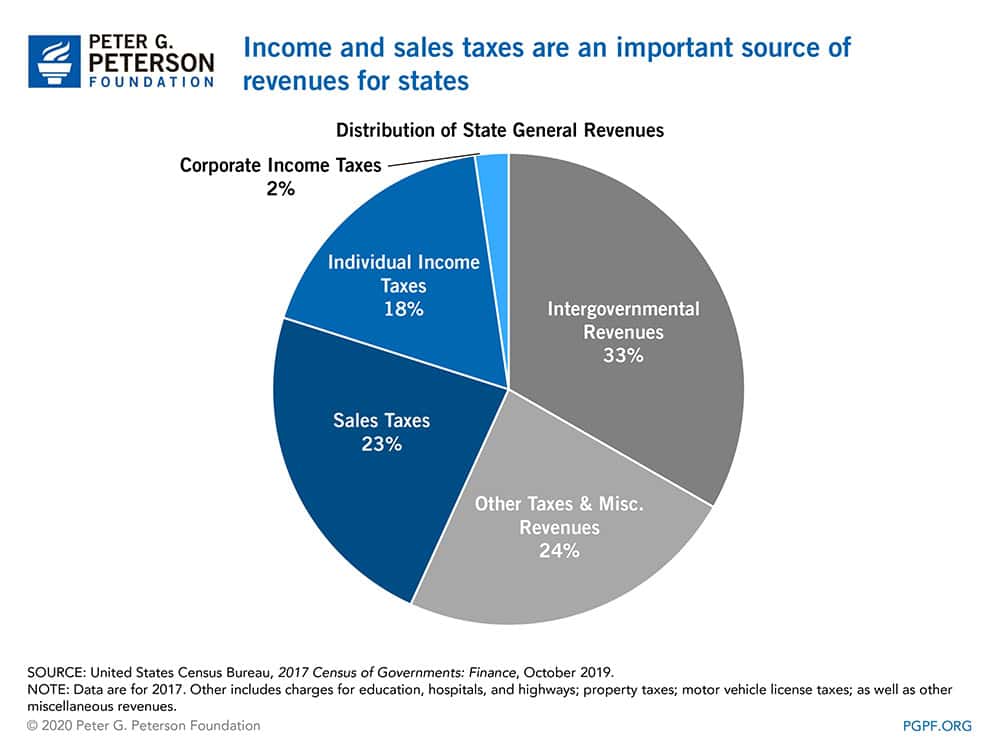

Necessary public health measures put in place to limit the spread of the pandemic have reduced employment and dampened spending on goods and services. State and local governments rely on taxes derived from such activities and are therefore experiencing significant declines in revenues. At the same time, COVID-19 has increased state spending on public health measures and social services.

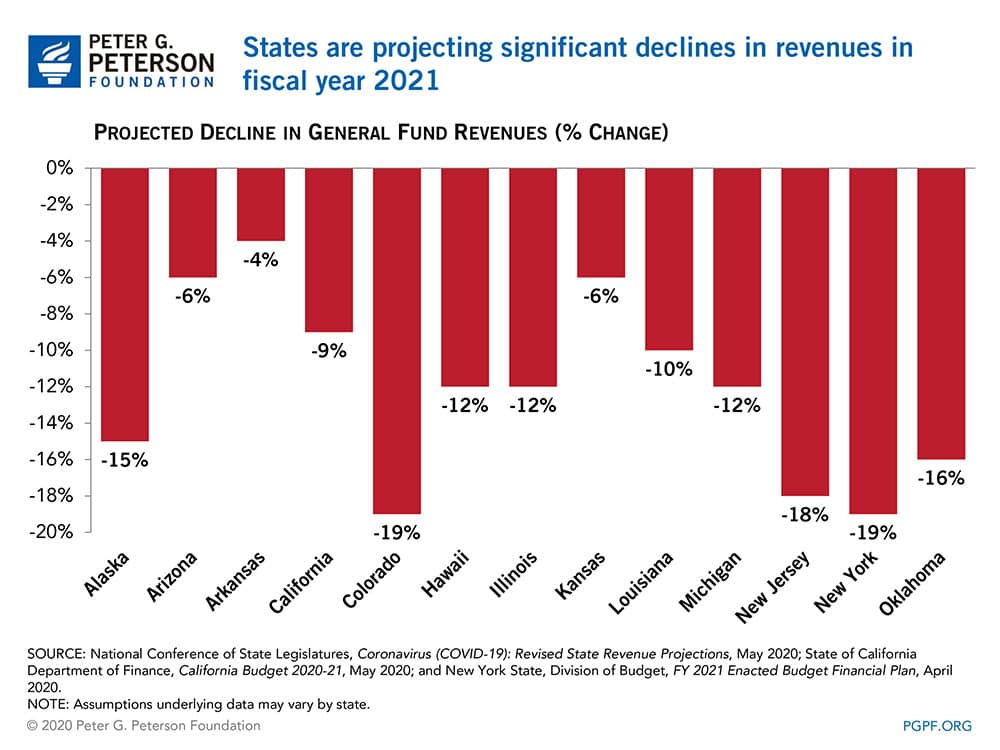

State budget offices across the country have begun to release preliminary estimates that anticipate revenue shortfalls for fiscal year 2021 (which begins in July 2020 in most cases). Those estimates shed light on different ways that states are being affected. States that were at the epicenter of the outbreak initially, namely California and New York, are estimating reductions in tax revenues of between 9 and 19 percent in fiscal year 2021 relative to prior forecasts. States with high concentrations of oil-related industries — such as Colorado and New Mexico — will see decreases in revenues that are compounded by lower oil prices. Those states anticipate declines of 19 and 20 percent, respectively, in fiscal year 2021.

In addition to declining revenues, states are facing increased short- and medium-term expenses. Many states are making supplemental appropriations to respond to the pandemic. Minnesota, for example, appropriated $330 million in funding to a COVID-19 fund as well as to agencies for food assistance, small business loan programs, and grants to tribal nations. Similarly, the legislature in California has allocated more than $1.4 billion in funding related to the pandemic response.

Furthermore, safety net programs will see added expenditures. For example, prior to the health crisis, Medicaid was the largest expenditure for states, making up 29 percent of their spending in 2019, on average. Enrollment in the program rises when unemployment increases, and while enrollment data are not yet available, analyses are projecting significant enrollment increases due to the large number of people who have lost jobs during the past few months. The increase in costs may be mitigated, though, because the federal government already shares the cost of Medicaid with states and the Families First Coronavirus Response Act temporarily increased the federal portion. In addition, non-urgent services were restricted during the public health crisis, lowering spending somewhat. Nevertheless, at least 18 states are anticipating increased Medicaid costs.

Other costs to states are also likely to grow. Public health spending is projected to increase, as many states have implemented policies to expand access to COVID-19 testing and treatment as well as to allow special-enrollment periods in state-based health insurance marketplaces. Spending on programs including cash assistance, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and social services are also anticipated to rise.

States Face Balanced Budget Requirements and Limited Opportunities for Issuing Debt

Unlike the federal government, nearly every state has a version of a balanced budget requirement. Those measures generally require annual balance in a given state’s operating budget, though they can borrow for capital projects and certain other limited uses. States must therefore look for approaches other than debt issuance to address any imbalance between revenues and spending.

Federal assistance is one such measure. Most additional federal support thus far related to the pandemic was provided in the CARES Act, which allocated about $200 billion in funding for:

- The Coronavirus Relief Fund, which provides direct fiscal support to governments to cover expenditures incurred during the health emergency ($150 billion)

- The Education Stabilization Fund, which includes discretionary grants to states with the highest coronavirus burden, emergency grants for elementary and secondary schools, and funding for higher education ($31 billion)

- Mass transit agencies ($25 billion)

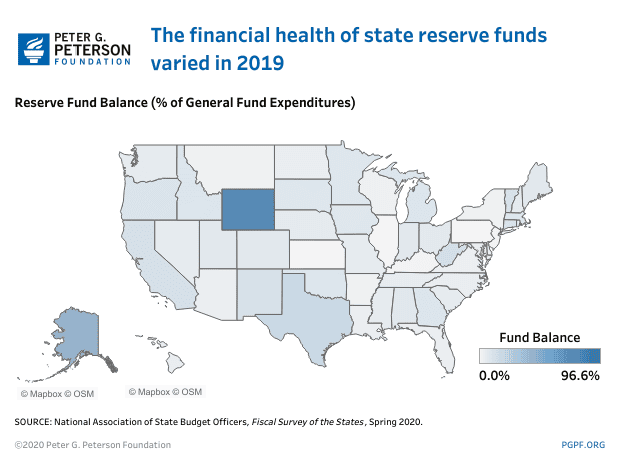

Another solution is revenue stabilization funds, or rainy day funds, which are essentially state savings accounts that help them withstand economic downturns. Collectively, states entered the pandemic with a larger fiscal cushion than they had ever had previously, with $72.3 billion in reserves and a median balance reaching 7.6 percent of general fund spending in fiscal year 2019. Some states were less prepared than others; for example, Kansas, Illinois, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania reported fund balances of only 1 percent or less of general fund expenditures. A number of states have already made use of their reserve funds to help mitigate the impact the pandemic will have on their budgets. Arizona, for example, transferred $55 million from their fund to the Public Health Emergencies Fund to help pay for the response, while South Carolina appropriated $45 million from their fund. Most recently, California’s governor declared a budget emergency that will allow the state to use its reserve fund during the next fiscal year.

It is likely that states will also revisit their budget choices in response to falling revenues. While certain states may consider tax increases, precedent suggests that states will rely on spending reductions. States such as Ohio, Colorado, Georgia, and New York have all already announced reductions in social services and Medicaid spending even as enrollment has increased. New York, Tennessee, and Indiana (among others) have also frozen hiring.

Finally, under certain circumstances, states may resort to borrowing. One way to do so is to borrow funds from the federal government to cover unemployment insurance costs; 11 states have already done so. States and municipalities may also be able to issue short-term debt, which could be used to cover temporary cash flow deficits. Such short-term debt often carries higher interest costs and is subject to a lot of volatility, so the Federal Reserve has created a new Municipal Lending Facility intended to smooth the functioning of these markets and serve as a lender to states and municipalities seeking to issue certain types of short-term securities.

Effect of Austerity by States and Localities

It is too early to know what the longer-term ramifications of the pandemic to state budgets will be, but the end of the Great Recession may be an instructive example. By 2013, state and local government revenues had returned to pre-recession levels, but lasting damage was nevertheless felt. The drastic measures state and local governments took to balance their budgets may have lengthened the time it took the economy to recover, and such reductions often remained in place. Nearly half of states were spending less in 2018 than they had a decade prior, after adjusting for inflation, and funding for higher education remained 13 percent lower in 2018 than in 2008. Funding for K-12 education and infrastructure were also lower in many states.

State and local governments are the fifth largest contributor to gross domestic product, comprising 9 percent of national economic activity in 2019, so their recovery after a recession is a significant factor in the wider national recovery. An analysis by the Tax Policy Center found that during the recovery from the Great Recession, state and local government activity fell rather than mirroring the wider recovery, an unprecedented occurrence. Consumption and gross investment fell by 4 percent over the period, though in recoveries from previous recessions it had grown by 6 percent, on average. That led to a decrease in payrolls of 3 percent, though in previous recoveries state and local employment grew by 3 percent on average. The authors conclude that rather than aiding in the recovery, the state and local government sector proved to be an economic drag.

Looking ahead, federal lawmakers will likely consider this range of factors in determining whether to answer the calls for additional assistance from state and local government leaders.

Image credit: Photo by iStock/Getty Images

Further Reading

How Do Quantitative Easing and Tightening Affect the Federal Budget?

The Federal Reserve plays an important role in stabilizing the country’s economy.

How Do Federal Student Loans Affect the National Debt?

Student debt held has been steadily increasing ever since the federal government switched to direct lending.

How Does Climate Change Affect the Federal Budget?

Climate change and its effects already impose a cost on the American economy and the federal budget.