Real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 1.9 percent in the third quarter of 2019, according to today’s announcement by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. That rate of growth is slightly below the 2 percent growth in the second quarter of 2019 and noticeably lower than the 3.1 percent growth recorded in the first quarter. As is standard practice, this GDP estimate is subject to revision; a more accurate estimate will be released at the end of November.

Growth in the third quarter was led by personal consumption expenditures and government spending, though such categories grew more slowly than in the second quarter. Meanwhile, the deficit just hit a seven-year high, and is expected to continue to rise in the years ahead.

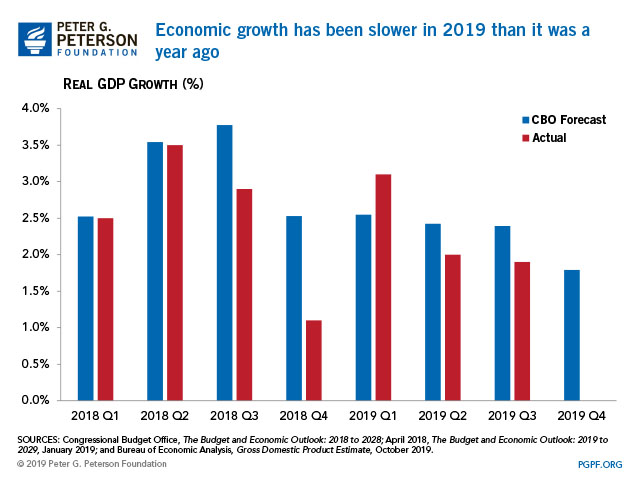

Growth Has Slowed Compared to 2018

Growth rates in 2019 are on track to be lower than in 2018, largely conforming to forecasted trends. Growth earlier in the year was spurred by appropriations enacted in early 2018 as well as by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), though the stimulus effects of the latter are fading. A strong job market and consumer spending also contributed to growth. However, trade tensions and a slowing global economy partially offset those effects.

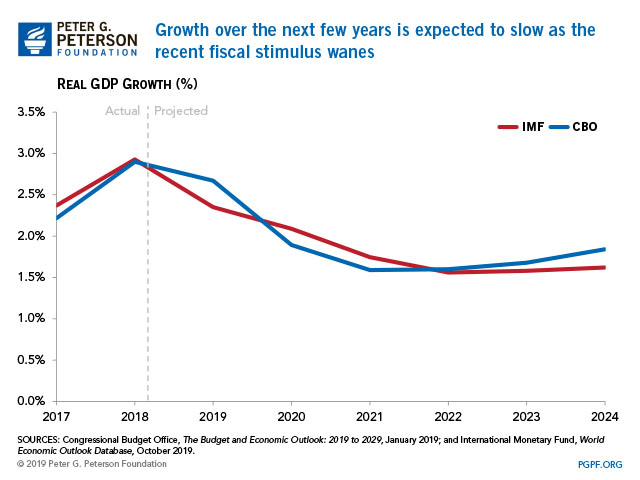

Growth Rates Will Ebb over the Next Decade

Looking further into the future, forecasters believe that growth rates will continue to ebb as the GDP-boosting effects of the TCJA and increased appropriations fade. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) revised its forecast for growth in 2019 to 2.4 percent, and it expects growth to soften further to 2.1 percent in 2020 as fiscal policy becomes less expansionary.

The Deficit Is Rising during a Period of Strong Economic Growth

Normally, rapid growth in GDP like that seen in 2018 and the early part of 2019 would lead to a reduction in the deficit as revenues increase and spending for programs such as unemployment compensation decreases. However, despite the ongoing economic expansion and low unemployment, our fiscal outlook is worsening — a highly unusual occurrence. This is happening because the positive fiscal effects of economic growth have been more than offset by legislative changes that have widened the gap between revenues and spending.

Both CBO and the IMF assess that economic growth has cooled but will remain steady, as slow expansion of the labor force and levels of productivity similar to historical averages will limit GDP growth in the future. Now, while the economy remains strong, lawmakers should take advantage of the opportunity to get our fiscal house in order. There’s no reason to be piling debt onto future generations — especially during a strong economy — and there is no shortage of options to pay for priorities while improving our fiscal sustainability.

Image credit: Photo by tacojim/Getty Images

Further Reading

New Report: Rising National Debt Will Cause Significant Damage to the U.S. Economy

On all key financial metrics, from GDP and investment to jobs to wages, the growing national debt harms future economic prospects for American citizens.

The National Debt Can Crowd Out Investments in the Economy — Here’s How

Large amounts of federal debt could “crowd out” investments by the private sector, making the economy less productive and stunting wage growth.

National Debt Puts Upward Pressure on Inflation and Interest Rates

America’s unsustainable fiscal outlook can have “significant consequences for price stability, interest rates, and overall economic performance,” according to a new report.