Many experts who follow federal budget issues argue that a primary reason to keep debt under control is to ensure that policymakers have “fiscal space” to respond to a crisis. Lower levels of debt allow governments to respond more aggressively to a recession or financial crisis by reducing tax collections or increasing spending. Put another way, prudent fiscal policy can act as an insurance policy against future economic downturns.

Recent analysis from economists Christina Romer and David Romer in their working draft titled “Fiscal Space and the Aftermath of Financial Crises: How It Matters and Why” follows up on previous research looking at how advanced economies respond to financial crises. Romer and Romer find that countries with more “fiscal space” do in fact respond more aggressively when confronted with a financial crisis, thereby mitigating the negative effects more effectively than their high-debt counterparts.

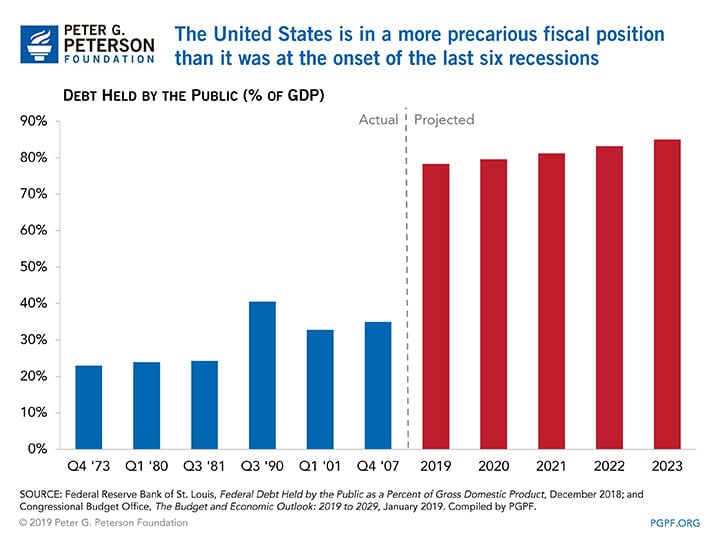

Debt held by the public in the United States as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) at the beginning of the last six recessions averaged 30 percent. In contrast, at the end of 2018, debt held by the public reached 78 percent of GDP, more than twice the average at the beginning of the last six recessions and the highest level since 1950; the Congressional Budget Office projects that the debt-to-GDP ratio will grow to 85 percent by 2023.

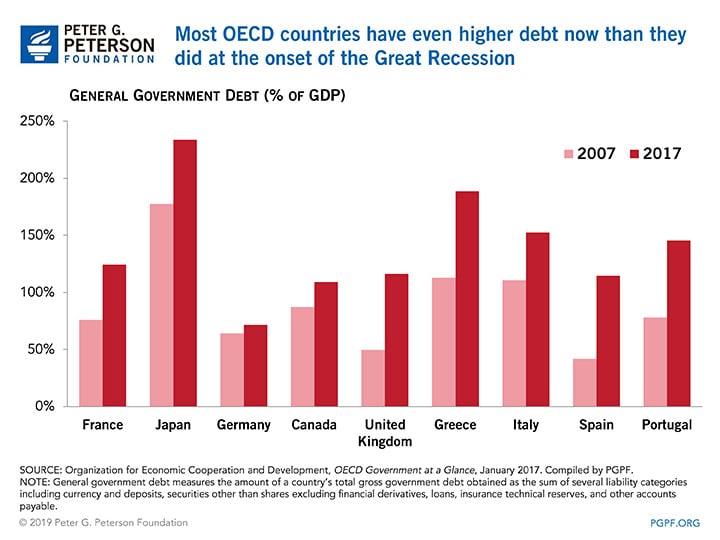

Romer and Romer argue that there are two explanations for why high-debt countries respond to financial crises less effectively. First, high-debt countries typically have greater difficulty accessing debt markets than do lower-debt countries. This can be seen in the recent experiences of Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal, countries that faced relatively high interest rates in their sovereign debt markets because of the perception that those countries would have difficulty paying back their debt.

However, the second and more important reason high-debt countries are relatively austere during financial crises is that they choose to be. Romer and Romer suspect one possible explanation for this is fear of the substantial risks that future high debt positions would pose. Another possible explanation is that policymakers simply might not want the increased burden of servicing higher debt.

Fears of a recession hitting the U.S. are increasing, particularly because the current economic expansion is poised to become the longest sustained expansion in post-war history. Indeed, the most recent survey by the National Association for Business Economics shows that 75 percent of respondents forecast a recession sometime before the end of 2021. In light of this prediction, consider the United States’ current fiscal position.

Given the historically high levels of debt and its projected increase, it is more and more likely that the United States will not have the “fiscal space” to respond aggressively to the next recession. Therefore, the United States’ present fiscal position may contribute to a lengthier and more challenging recovery from the next financial crisis, the pain of which would be felt by all Americans.

Image credit: Photo by Chris Hondros/Getty Images

Further Reading

Growing National Debt Sets Off Alarm Bells for U.S. Business Leaders

Debt rising unsustainably threatens the country’s economic future, and a number of business leaders have signaled their concern.

What Is R Versus G and Why Does It Matter for the National Debt?

The combination of higher debt levels and elevated interest rates have increased the cost of federal borrowing, prompting economists to consider the sustainability of our fiscal trajectory.

High Interest Rates Left Their Mark on the Budget

When rates increase, borrowing costs rise; unfortunately, for the fiscal bottom line, that dynamic has been playing out over the past few years.