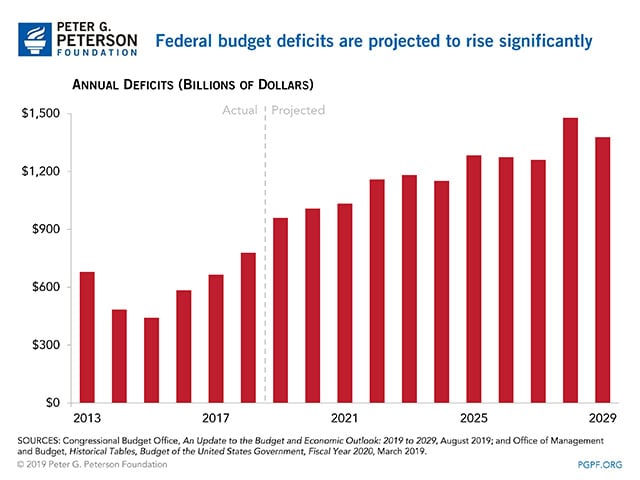

As a share of the economy, the national debt is at its highest level since immediately after World War II. Annual deficits are approaching $1 trillion and they are projected to increase with no end in sight. That unsustainable trajectory poses a significant risk to the nation’s economic future, yet a comprehensive solution to manage the debt has proven elusive for lawmakers.

To this end, Brian Riedl — a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute — wrote a report detailing the three key ingredients for negotiating a deficit-reducing budget deal that would put America on a more sustainable path.

Why Do We Need to Reduce the Federal Debt?

High federal debt can have negative effects on the U.S. economy by reducing private and public investment, by limiting the country’s fiscal flexibility to deal with a recession, and by creating fewer economic opportunities for Americans. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the annual deficit is expected to reach 4.5 percent of GDP this year — its highest level since the aftermath of the financial crisis. Even more concerning, under current law annual deficits are projected to remain around that level for the next decade. Such high deficits drive growth in federal debt, which is projected to rise faster than that of any other country over the next five years.

The Three Ingredients for a Fiscally Responsible Budget Deal

The growing debt, and the negative ramifications that come with it, demonstrate the need for lawmakers to negotiate fiscally responsible solutions. However, such deals have been relatively rare. The Manhattan Institute’s report examines 14 major budget negotiations — both successful and unsuccessful — and found that effective deficit-reduction efforts feature two of the following three key ingredients:

1. A Penalty Default

If policymakers are unable to enact a deal by a certain deadline, a penalty default would automatically occur — thereby implementing a policy that is unpopular for both political parties. In 2013, for example, a tax deal was reached largely due to the coming expiration of provisions originally enacted in 2001 that would have significantly increased taxes — an unpopular result that neither side wanted. In this sense, a penalty default serves as an incentive for each side to overcome their partisan differences and reach a compromise within the allotted time.

The report argues that for a penalty default to be effective, however, at least one party must be willing to risk the outcome of the penalty in order to reach a deal. If a penalty default is too strong and neither side wants to risk the outcome, lawmakers may repeal the penalty altogether. If the penalty is too weak, on the other hand, policymakers may not be motivated to negotiate a deal.

2. Public Support

Another key element to a successful negotiation, according to the Manhattan Institute’s report, is that the potential deal must have enough public support across both parties. Deficit-reduction deals may be popular among voters in theory, but the necessary actions to achieve one — such as tax increases or spending cuts — may lead to public opposition. However, factors such as bipartisan credibility and a tangible public payoff can help bolster public support. When a deficit-reduction deal has bipartisan support from lawmakers, it helps to relieve voter concerns of any disproportionate outcomes. Likewise, a tangible public payoff — such as averting a government shutdown or reducing income inequality — can also help shore up public support.

3. Personal Relationships, Trust, and Integrative Negotiations

The report concludes that the third, and perhaps most critical, ingredient of a successful budget negotiation is building trust and a good working relationship between the negotiating parties. This involves entering the negotiation in good faith — showing respect, a willingness to compromise, and not undermining the opposing side — and by using an integrative negotiating strategy (in which policymakers collaborate to find a compromise that benefits both parties).

The report includes the example of President Reagan and House Speaker O’Neill as they began their Social Security negotiations in 1982 with a pledge not to publicly attack one another or the Social Security commission they formed. Another example mentioned in the report is from 1997, when a budget deal was also reached between President Clinton and Speaker Gingrich because they decided to forgo the political warfare that caused the budget deal from the prior year to collapse. In both examples, Riedl writes, acting in good faith and seeking a win-win compromise helped each party reach an agreement.

In addition to those three key ingredients, the report identifies several secondary ingredients that can help lawmakers reach a deficit-reduction deal. For more on these, as well as an examination of the historical case studies, view the report on the Manhattan Institute’s website and their podcast discussion below.

Image credit: Photo by Samuel Corum/Getty Images

Further Reading

How Did the One Big Beautiful Bill Act Affect Federal Spending?

Overall, the OBBBA adds significantly to the nation’s debt, but the act contains net spending cuts that lessen that impact.

What Is the Disaster Relief Fund?

Natural disasters are becoming increasingly frequent, endangering lives and extracting a significant fiscal and economic cost.

How Much Does the Government Spend on International Affairs?

Federal spending for international affairs, which supports American diplomacy and development aid, is a small portion of the U.S. budget.