Taxing the Rich Could Raise Trillions — But That Alone Won’t Fix Our Fiscal Crisis

Last Updated December 19, 2023

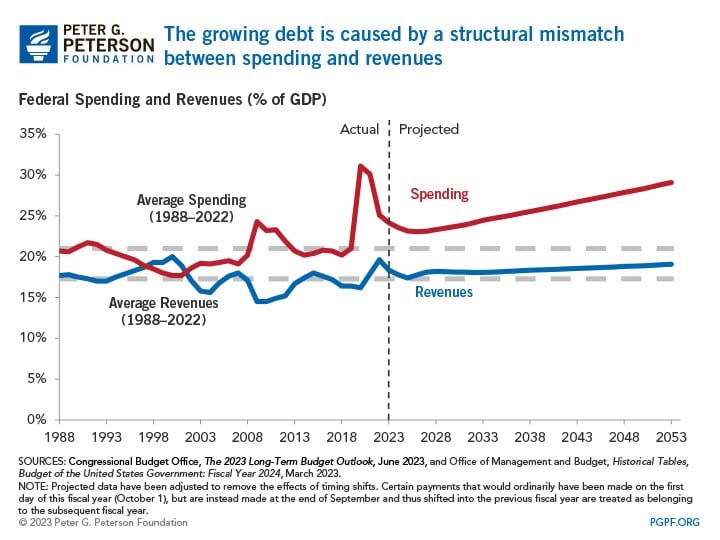

Because of the structural mismatch between federal spending and revenues, the budget deficit from fiscal year 2023 was $1.7 trillion, or 6.3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). By 2053, the budget deficit is projected to reach 10.0 percent of GDP.

So when it comes to finding solutions to our fiscal challenges, there’s no doubt we need to look at every tool in the toolbox. A new paper from Manhattan Institute’s Brian Riedl examines ways to raise revenue from high-income Americans, how much of the fiscal gap could be closed by “taxing the rich”, and why even more deficit reduction beyond taxing the rich will be required to stabilize the country’s debt.

Revenues in the United States

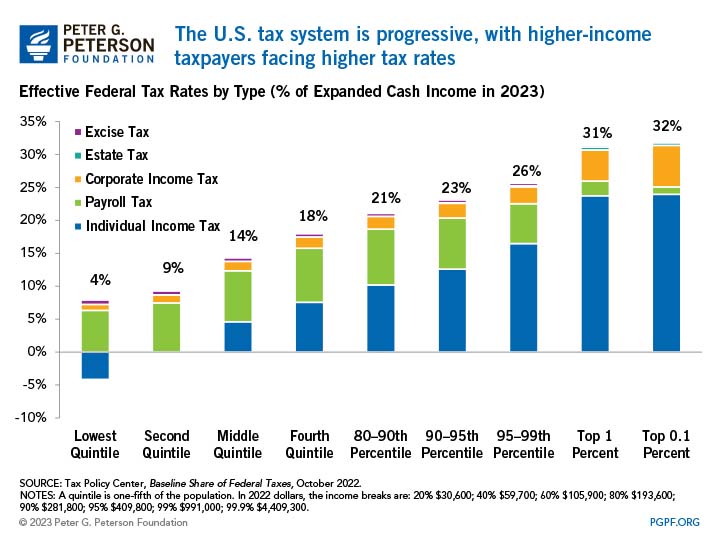

The tax system in the United States is set up to be progressive, meaning the more a household earns in income, the larger the proportion of taxes paid. For example, households in the top 1 percent of the U.S. income distribution pay an effective federal tax rate of 31.4 percent, while households in the bottom 20 percent are taxed at an effective federal rate of 3.8 percent. At the same time, wealthier taxpayers benefit disproportionately from tax breaks, such as deductions, credits and preferential rates.

What Impact Would Taxing the Rich Have on the United States?

As income and wealth inequality has grown, many policymakers and experts have called for higher taxes on wealthy Americans. Often, there are different definitions of wealthy. One common category used is families with earnings in the top 1 percent ($686,100 for a family of two in 2023). Another threshold used is families with income over $400,000, which equates to the top 2 percent in the United States. A majority of proposals to tax the rich address individual income taxes, but the wealthy can also be taxed through other avenues, such as capital gains, the estate tax, and the corporate tax rate.

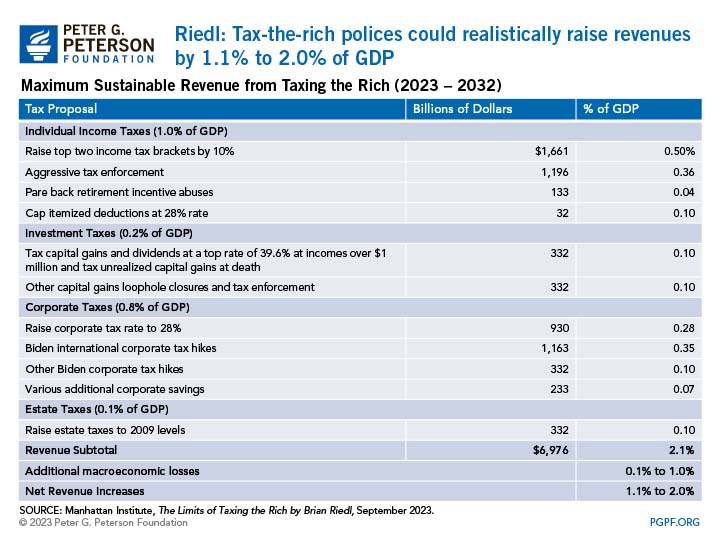

Riedl looks across the several categories of revenue that could be called “taxing the rich” and proposes a “maximum sustainable revenue” proposal for each — which is to say, he proposes the highest amount revenue that could be gained from each category without harming the economy. Riedl finds that raising individual income taxes on the wealthy would generate the most revenues, estimating that about 1.0 percent of GDP over 10 years could be raised from that category alone.

Other sources of potential new revenues include hikes on corporate taxes (0.8 percent of GDP), investment taxes (0.2 percent of GDP), and estate taxes (0.1 percent of GDP). In all, the maximum sustainable revenue from the proposals Riedl analyzed would raise revenues by, at most, 2.1 percent of GDP in total over the next decade. However, Riedl estimates that that number is more realistically in the range of 1.1 to 2.0 percent of GDP when accounting for macroeconomic responses.

While that range of savings from “tax the rich” policies is significant, representing nearly $7 trillion of potential deficit reduction over a decade, it is not sufficient, by itself, to stabilize the debt over the long term. Riedl assesses the noninterest savings required to stabilize the debt will be at least 5.0 percent of GDP.

What Are Other Ways to Raise Revenues?

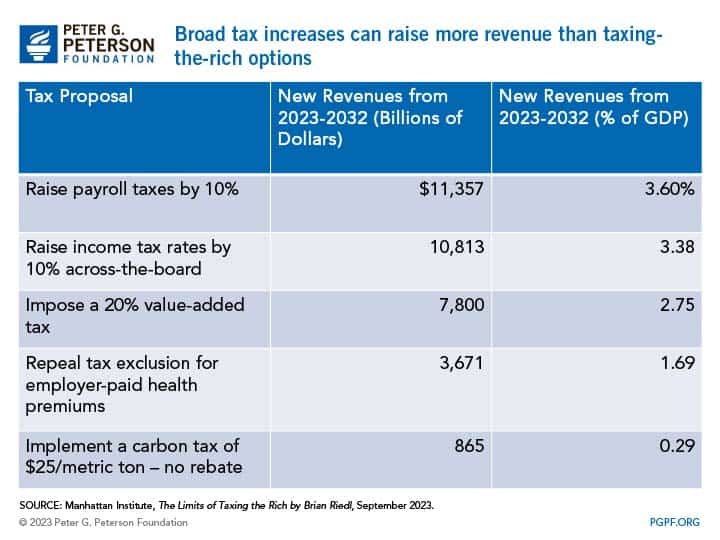

Given the gap between what is needed to stabilize the debt and what Riedl argues is possible through taxing the rich, he suggests that tax policy should apply to a broader base or bring in new sources to raise sufficient revenues. For example, the tax exclusion for employer-paid health premiums is one of the largest tax breaks in the U.S. tax code, therefore indicating a source for untapped revenues. Another option is to impose a carbon tax, which 46 countries utilize to both raise revenues and reduce carbon emissions.

Furthermore, implementing a 20 percent value-added tax (VAT) would also help raise revenues. Out of the countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which is a member group of high-income countries, the United States is the only country that does not have a VAT. The lack of a VAT is the central reason why countries in the OECD collect an average 34.1 percent of GDP in revenues while the United States collects 26.6 percent of GDP. Excluding VATs, OECD nations collect an average 26.9 percent of GDP in revenues.

For additional savings, Riedl points to reducing spending programs that benefit upper-income families. He finds that $1 trillion could be saved over the next decade if farm subsidies for large agribusinesses were scaled back and if Medicare subsidies and Social Security benefits for retirees with (non-housing) net worth in the millions were reduced.

Why Revenues from Taxing the Rich Could Fall Short of Projections

It is unarguable that there is significant potential to raise revenues by taxing wealthy individuals and corporations. However, Riedl and other experts caution that policymakers need to be aware of the potential for associated macroeconomic impacts. Responses to higher tax rates could result in the following:

- Income shifting: Upper-income families may shift their compensation from wages to tax-advantaged fringe benefits. That includes shifting compensation to lower-taxed capital gains or corporate income, moving income overseas, or engaging in more aggressive tax evasion.

- Short-term responses: Those with the financial flexibility may reduce the amount of time working or take more unpaid vacations.

- Medium-term responses: Secondary earners or spouses may exit the labor market and decide to instead stay home (especially if the second person’s income pushes the family into a higher tax bracket). Entrepreneurs may also be less likely to create or expand businesses because of smaller potential payoff.

- Long-term responses The next generation of workers may shift to less lucrative college majors and career choices because higher tax rates reduce the reward.

Riedl contends that the point is not that tax rates should never rise; however, the broader economic implications of each tax must be weighed and traded off with federal spending goals.

Riedl contends that the point is not that tax rates should never rise; however, the broader economic implications of each tax must be weighed and traded off with federal spending goals. Reducing the economy’s annual economic growth rate by 1.0 percentage point of GDP would decrease tax revenues by $3.3 trillion over the decade.

Conclusion

With the federal budget deficit projected to reach 10.0 percent of GDP in 30 years, Riedl argues that tax increases can — and should — begin with the wealthy, but lawmakers cannot rely on that as the sole way of raising revenues to offset federal spending. An aggressive package of new taxes on corporations and the top 1 percent to 2 percent of households could raise, at most, 2.1 percent of GDP in revenues – meaningful, but not sufficient to stabilize the debt. Riedl’s report emphasizes that lawmakers need to find additional ways to reduce the large federal deficit, and creating smart tax policy is a key point in achieving that goal.

Image credit: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Further Reading

Infographic: How the U.S. Tax System Works

One issue that most lawmakers and voters agree on is that our tax system needs reform.

No Taxes on Tips Would Drive Deficits Higher

Eliminating taxes on tips would increase deficits by at least $100 billion over 10 years. It could also could turn out to be a bad deal for many workers.

Should the U.S. Change the Corporate Tax Rate in 2025?

Here’s why lawmakers lowered the corporate tax rate in 2017, how the lower rate impacted the U.S., and how the rate might be reformed in 2025.