How Has the Coronavirus Affected the U.S. Economic Outlook

Last Updated May 22, 2020

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and the government’s response to mitigate its effects have drastically altered the U.S. economic outlook. Before the pandemic, the U.S. economy was in its longest expansion since World War II and had notably low unemployment. The pandemic and the resulting reductions in social and economic activity, however, have altered that trajectory.

To assess how the pandemic altered the nation’s economic path, this blog compares the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) 10-year economic projections from their January 2020 outlook, which were completed before the social and economic restrictions were implemented, to their projections released this week — which include an assessment of the pandemic’s effects. Below are the takeaways from such comparisons.

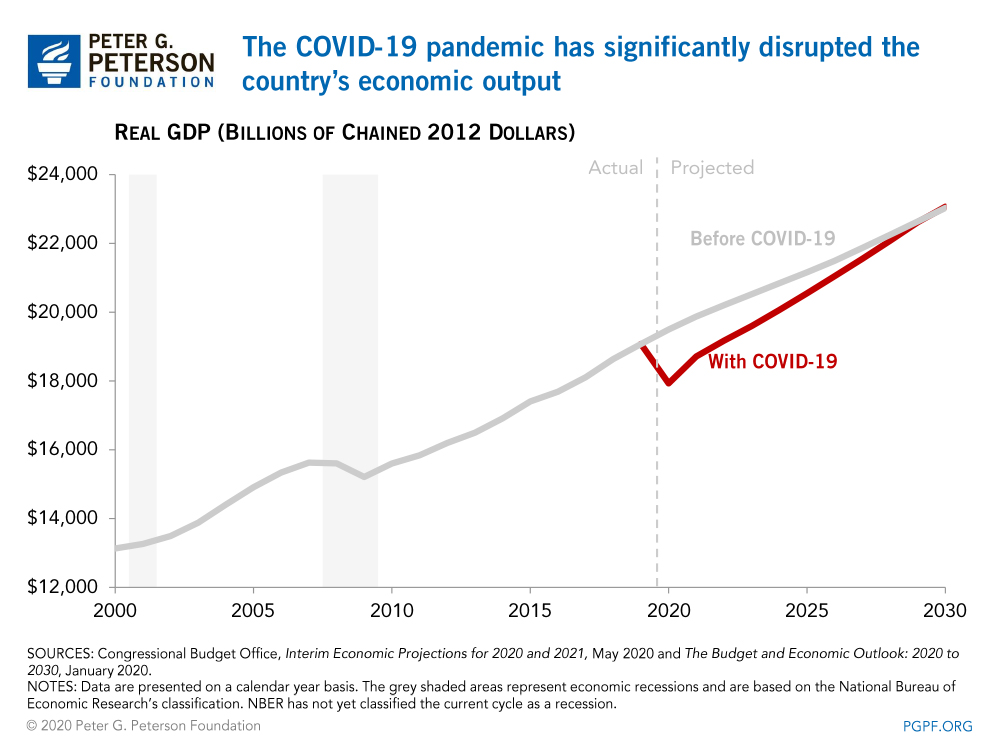

1. It may take several years for the country’s economic output to get back on track. Before the pandemic, the U.S. economy was expected to slowly continue its expansion. However, the social and economic restrictions put in place to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 led to a drastic and sudden reduction in economic activity. After dropping by an annualized rate of 4.8 percent in the first quarter of 2020, CBO anticipates that real gross domestic product (GDP) will decline even further in the second quarter of this year (April to June), at an annualized rate of 37.7 percent. For the full year, real GDP is expected to decline by 6.0 percent in 2020. That figure is expected to rebound in 2021, growing by 4.4 percent, and continue rising by around 2.4 percent annually throughout the rest of the decade. Nevertheless, CBO reports that real GDP will not catch up to the level they projected a few months ago until 2030 — indicating that the pandemic will have a lasting economic impact.

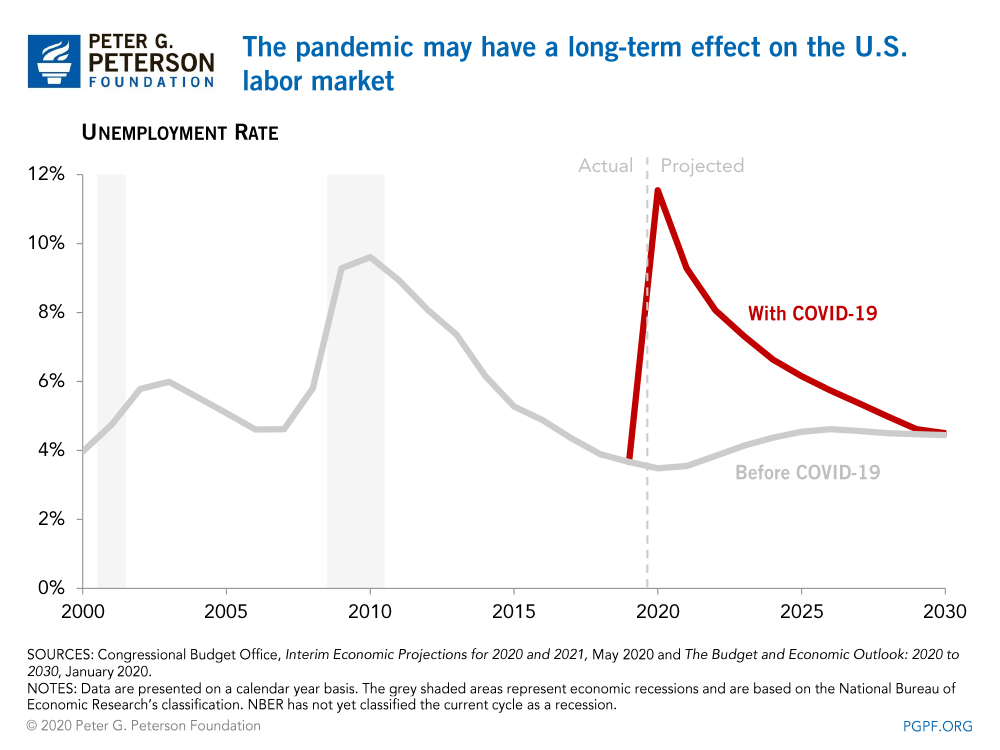

2. The pandemic may have a significant, long-term effect on the U.S. labor market. In the second quarter of 2020, CBO expects that the labor market will witness its steepest decline since the 1930s, with the average unemployment rate climbing to 15.0 percent. For the full year, CBO anticipates that the unemployment rate will average 11.5 percent. That marks a surge from the 3.7 percent rate recorded in 2019, which was the lowest annual rate recorded in 50 years. CBO expects the unemployment rate to gradually decline in the following years, but remain above their previous forecast throughout the decade.

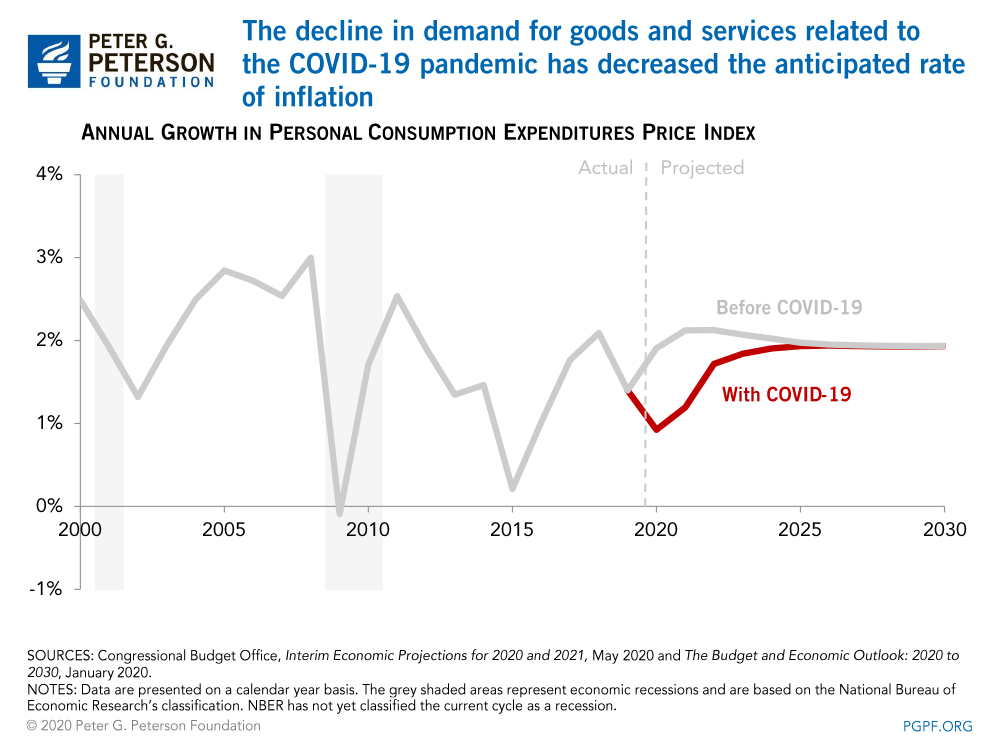

3. The coronavirus has led to a reduction in demand for some goods and services, lowering inflation. The COVID-19 pandemic and the government’s response to it have caused the demand for some goods and services to decline — reducing the prices for some items as a result. The growth in the price index for personal consumption expenditures, the measure that the Federal Reserve uses for its 2.0 percent inflation benchmark — is expected to drop to 0.9 percent this year and then gradually rise to 1.9 percent by 2024, remaining at that level throughout 2030. Prior to the social and economic restrictions put in place, inflation was expected to remain around 2.0 percent throughout the next decade.

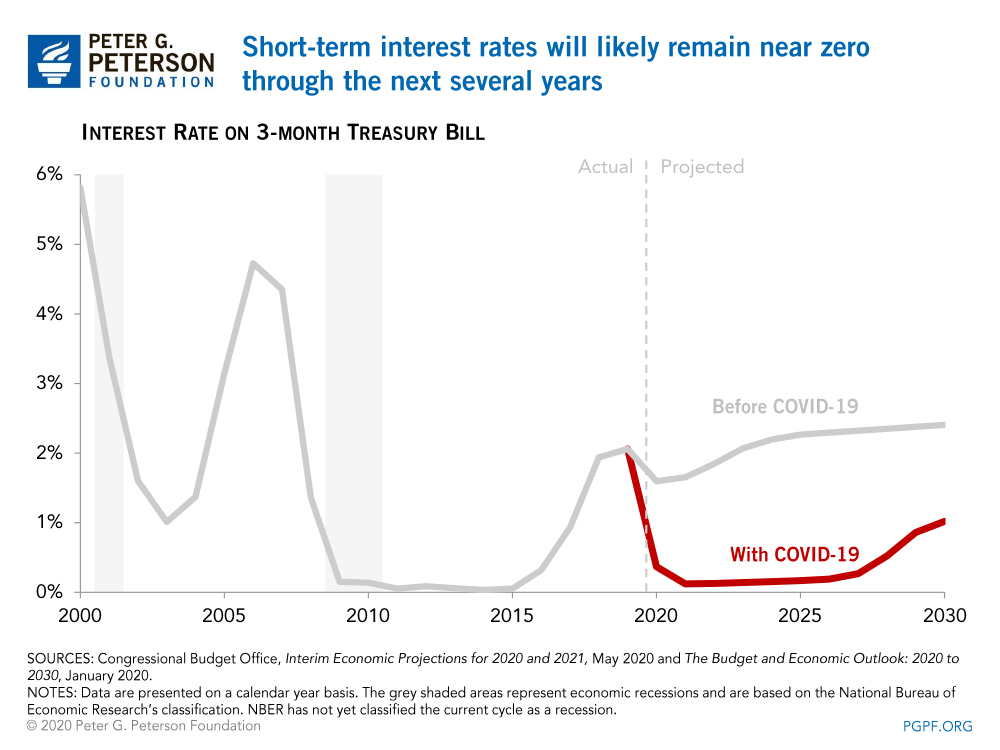

4. Short-term interest rates could remain near zero throughout most of the next decade. In January, CBO anticipated that the interest rate on 3-month Treasury bills would reach 1.6 percent in 2020 and gradually rise to 2.4 percent by 2030. That projection was based on the expectation that the Federal Reserve would gradually raise the federal funds target rate (the interest rate at which commercial banks lend to each other overnight) to keep inflation in check as the economy was expected to continue growing. However, those factors have changed drastically as the COVID-19 pandemic has reduced economic activity and CBO now expects the Federal Reserve to maintain a target rate of nearly zero to support economic recovery. As such, CBO anticipates that the interest rate on 3-month bills will drop to 0.4 percent this year and remain below 1.0 percent throughout most of the next decade.

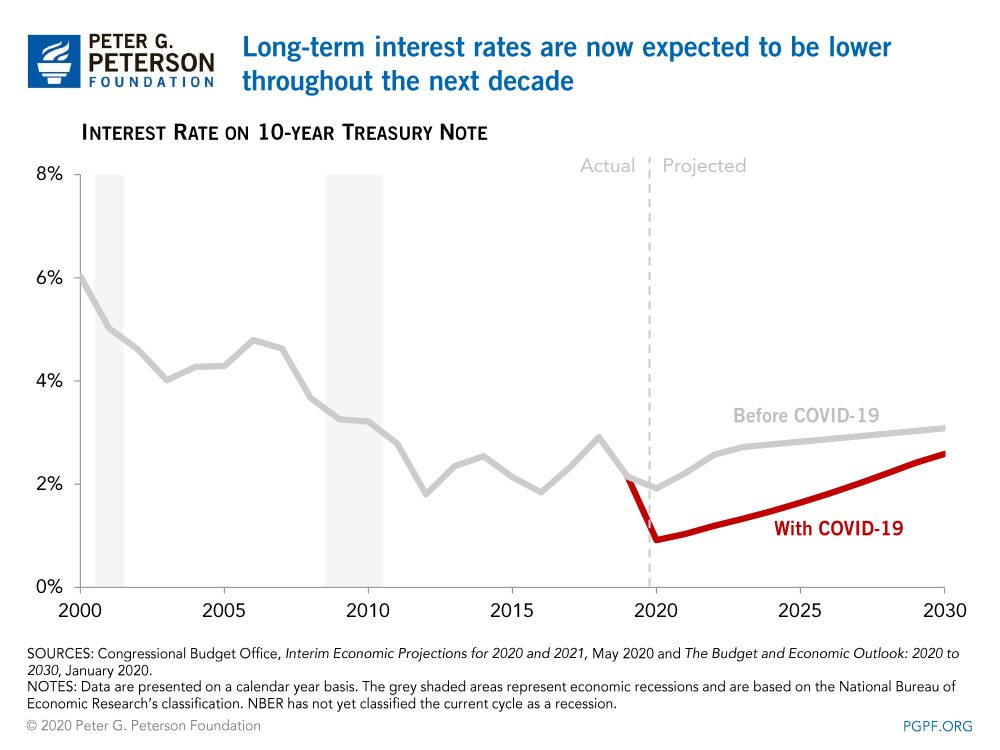

5. After a sharp decline, it could take years before rates on longer-term Treasury securities begin to rise noticeably. In their projections a few months ago, CBO anticipated that the 10-year rate on Treasury notes would remain relatively stable at around 2–3 percent over the next decade. However, the pandemic has led to an increased demand of such low-risk assets and, in conjunction with the Federal Reserve’s purchases of various Treasury securities, those long-term rates fell to historic lows and are now expected to rise very gradually in upcoming years.

CBO’s latest economic projections highlight the lasting damage the COVID-19 pandemic may have on the U.S. economy. However, as the agency notes, the outlook for the economic variables noted above are uncertain as they are influenced by the course of the pandemic as well as by the social and economic restrictions to mitigate its effect. When the economy eventually recovers, though, sustaining that recovery will require a focus on the nation’s underlying fiscal issues.

Image credit: Getty Images

Further Reading

National Debt Puts Upward Pressure on Inflation and Interest Rates

America’s unsustainable fiscal outlook can have “significant consequences for price stability, interest rates, and overall economic performance,” according to a new report.

Why Is the Federal Deficit High If Unemployment Is Low?

The U.S. is experiencing an unusual and concerning phenomenon — the annual deficit is high even though the unemployment rate is low.

What Is Inflation and Why Does It Matter?

Here’s an overview of inflation, why it matters, and how it’s managed.