The debt ceiling was raised by $5 trillion — from $36.1 to $41.1 trillion — in July 2025, when the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) was signed into law. Prior to OBBBA’s passage, the Treasury had been implementing “extraordinary measures” to temporarily avoid default. Such measures include temporarily delaying certain investments and issuances. At the current pace, the United States will run through the $5 trillion debt limit increase in just two years.

What Are the Consequences of Not Raising the Debt Ceiling?

If lawmakers did not agree on raising or suspending the debt limit before the extraordinary measures were exhausted, there would have been severe consequences for both the federal government and the economy.

With spending limited to incoming revenues, the federal government could be forced to delay payments to employees, contracts would have been violated, and payments to beneficiaries of government programs (including Social Security and Medicare) could have been delayed or reduced. Although the Treasury Department would have probably continued making timely principal and interest payments on the public debt, worries about the government’s creditworthiness would likely have caused interest rates to rise and increase the government’s cost of borrowing. The Government Accountability Office estimated that delays in raising the debt limit in 2011 increased the government’s borrowing costs by $1.3 billion in that fiscal year; a subsequent report identified costs of $38 million to $70 million resulting from the debt limit impasse in 2013.

The threat of default puts into question America’s willingness to honor its commitments. Not only would that harm the country’s creditworthiness, it would also have effects on the economy. In a 2023 report from Moody’s Analytics, the credit rating agency found that even a short-term breach of the federal debt limit could reduce gross domestic product, result in the loss of 2 million jobs, and wipe out trillions of dollars in U.S. household wealth. A prolonged breach of the debt ceiling would likely amplify those effects.

Does the Debt Ceiling Control Government Spending?

No — raising the debt limit does not authorize new spending. Rather, raising the debt limit simply enables the Treasury Department to fund commitments that the government has already incurred under previous decisions by elected officials. To control actual spending, lawmakers must change the laws that provide funding in the first place.

What Is the History of the Debt Ceiling?

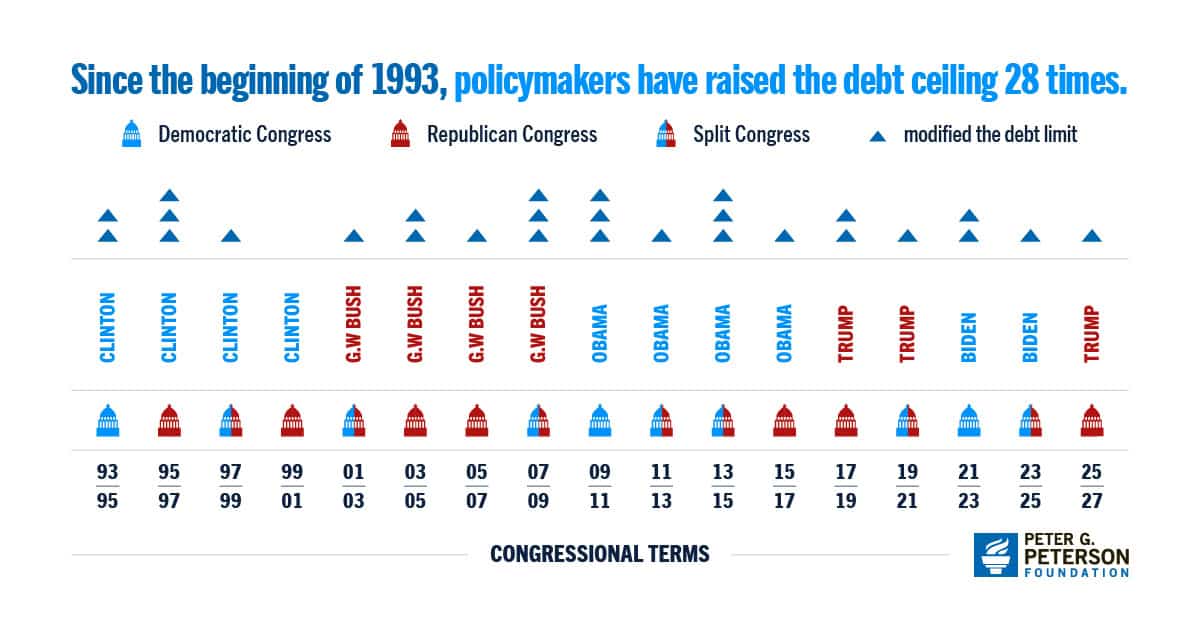

The debt limit has been raised frequently in the past — 91 times since the beginning of 1959, by Presidents and Congresses of both political parties. Since the beginning of 1993, policymakers have modified the debt ceiling 28 times. Lawmakers have addressed fiscal reforms as part of raising the debt limit, but in general the limit has not been effective in reining in the country’s growing debt.

Over the past 40 years, the debt limit has grown from just under $2 trillion to more than $41 trillion.

Conclusion

Stabilizing the debt is an essential part of any sound fiscal policy and economic strategy for the United States. Unless policymakers deal with the hard decisions to close the structural imbalance between spending and revenues, federal debt will climb to unsustainable levels and put the United States’ economy and future prosperity at risk. Addressing the country’s fiscal challenges is critical to ensure that there are adequate resources for investing in the future, protecting critically important programs, and creating robust economic growth and opportunity for coming generations.

Governing by crisis, engaging in fiscal brinksmanship, and threatening our nation’s creditworthiness are not effective means of addressing the fiscal situation. Instead of risking the full faith and credit of the United States, lawmakers should pursue the deep playbook of spending and revenue options to stabilize the debt and prevent the debt from rising so quickly.

Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Further Reading

What Is the Disaster Relief Fund?

Natural disasters are becoming increasingly frequent, endangering lives and extracting a significant fiscal and economic cost.

How Much Does the Government Spend on International Affairs?

Federal spending for international affairs, which supports American diplomacy and development aid, is a small portion of the U.S. budget.

A Brief History of U.S. Government Shutdowns

Government shutdowns (and the threat of them) are a recent phenomenon and something other developed countries don’t contend with.