A Path To Economic Prosperity

By Jason J. Fichtner and Shai Akabas

This paper is part of a new initiative from the Peterson Foundation to help illuminate and understand key fiscal and economic questions facing America. See more papers in the America's Fiscal and Economic Outlook series.

Over the years, the United States has moved from a nation of creditors to a nation of debtors; from a nation of savers to a nation of consumers. Recent events have made this reality abundantly clear. The federal government quickly responded to the economic fallout from COVID-19 by funneling trillions of dollars into Americans’ bank accounts. Although this financial relief made the personal savings rate jump, it also exposed the reality that pre-pandemic, more than 40% of households said they would struggle to afford an unexpected $400 expense. Tens of millions of households were living paycheck to paycheck, with little or nothing saved up.

Meanwhile, the $6 trillion pandemic response authorized by Congress accelerated another worrying trend: The national debt is soaring to unprecedented levels. Our annual shortfall, or dissavings, is captured by the federal deficit, which totalled $2.8 trillion in fiscal year 2021.

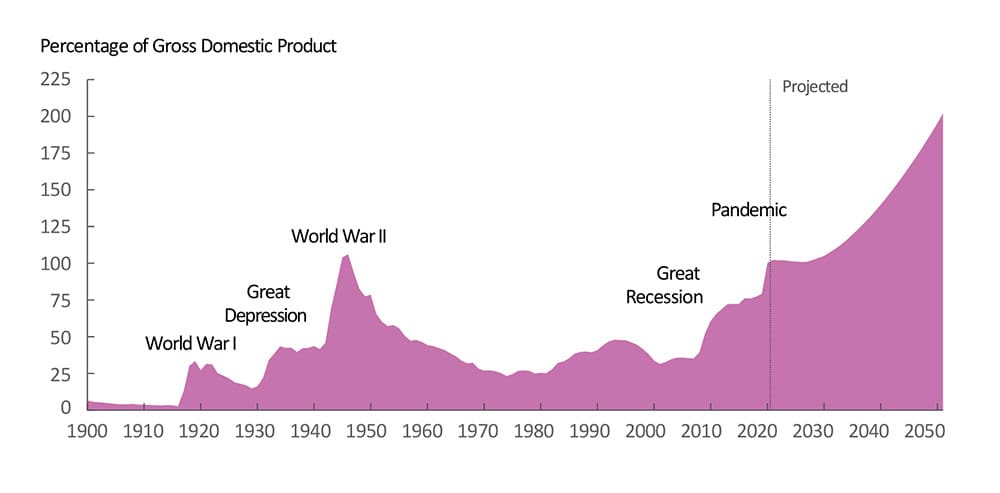

The Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC) has long been concerned with the trajectory of our public debt. In 2010, BPC convened a Debt Reduction Task Force of 19 former elected officials, private stakeholders, and experts — since then, their consensus final report has guided our work of encouraging fiscal responsibility. With debt held by the public relative to the size of the economy now higher than at any point since World War II and only projected to climb further, it is paramount that policymakers across the political spectrum recognize their responsibility to secure a sustainable economic future for the next generation.

Federal Debt Held by the Public, Percentage of GDP, 1900 to 2051

The Challenge of Rising Public Debt

Policymakers struggle with reining in red ink. Even during recent periods of economic growth, the federal government ran large and growing budget deficits, near $1 trillion per year. Now, the federal debt will only continue climbing as mandatory spending and interest payments on the debt grow faster than revenues. At the current rate, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that our debt could be double the size of the U.S. economy within 30 years.

With interest rates on U.S. debt near historic lows, some suggest that it is an ideal time for the government to borrow more money. This view is misguided for several reasons. First, it ignores the real potential that interest rates will increase, subjecting the federal government to higher annual interest payments. In 2021, the U.S. spent $413 billion on interest payments alone. At today’s debt levels, each 1 percentage point rise in the interest rate would increase annual interest spending by approximately $225 billion. This untroubled view also assumes that if and when interest rates do rise, policymakers will quickly compromise on the difficult choices necessary to restore fiscal order. Such an assumption runs counter to all existing evidence from recent U.S. history, where for example, trust funds for several major programs have remained starkly out of balance for years with no timely action by Congress in sight. Likewise, it overlooks the fact that the more palatable and equitable ways to address our debt burden involve gradual changes, rather than abrupt adjustments to tax or benefit programs. Implementing these reforms soon will provide adequate time to phase them in and avoid unnecessary economic and financial disruption.

Further, focusing only on the current low interest rate environment not only ignores the potential for a future interest rate shock, but also glosses over the fact that our nation’s greatest fiscal problems lie ahead. Interest spending is on track to become the largest federal program by 2045. Health care cost growth has been relatively muted over the past few years, but the ongoing retirement of baby boomers will continue to put more pressure on Social Security and Medicare finances; the return to more “normal” economic times after the pandemic subsides and the Federal Reserve winds down its bond-buying policies will likely bring higher interest payments as rates return closer to historical averages. Higher interest payments owed on the national debt will eventually force the government to make difficult fiscal tradeoffs, impacting every American household: Spending on other national priorities could decrease as it is relatively deprioritized against meeting our interest obligations, jeopardizing the very programs and services that millions of Americans — and especially vulnerable populations — depend on to sustain their livelihoods.

Such a scenario would pose great risk to the economy, as well as the nation’s global reputation, for years to come. Our country’s ability to lead on the global stage is determined, in part, by our economic competitiveness. Competitiveness demands that a nation’s producers contend within a global marketplace, and doing so successfully depends on an ability to employ its economic resources productively. While some debt-financed spending can be conducive to economic growth, high levels of debt can undermine competitiveness, particularly if sovereign debt becomes so large that servicing it redirects resources away from productive activity.

This crowding-out effect can impact not only federal spending but also private investment, as deficit financing borrows from and consumes capital that would otherwise be used by the private sector and the public to invest. The subsequent decrease in private investment would have spillover effects into the labor market, as employees ultimately bear the cost, through depressed wages and lower productivity, disincentivizing their participation in the labor force and contributing to a contraction of economic growth.

Directly related and perhaps most concerning — especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic — is that the growing federal debt could handcuff our ability to combat the next national or global emergency. Our capacity to respond effectively both at home and abroad could be severely inhibited by our incapacity to responsibly finance the nation’s needs. Ultimately, our high and rising debt burden risks exacerbating recessions or even triggering a financial crisis, as it could erode confidence in the fiscal position of the U.S. and deter lawmakers from using deficit financing as a prudent expansionary fiscal tool.

The Path Forward

As we consider solutions, it is important to acknowledge that fiscal responsibility is far from the only goal of economic policy. Among other challenges, the pandemic has accentuated and exacerbated many longstanding issues of income inequality and uneven economic opportunity that need to be addressed. The U.S. is thus at a crucial juncture to improve financial security and close equity gaps. Doing so with bipartisan support ensures that policies are sustained by their principles, not their politics.

At the height of the pandemic, emergency programs established by the federal government provided an instant financial buffer that helped reduce poverty by 21%. But beneath the macroeconomic success of expansionary fiscal policies that cradled the economy with enhanced unemployment benefits, expanded tax credits, rental assistance, and direct stimulus checks to households, among others, existed microeconomic inequities in the very systems designed to help those most in need. For example, people of color who filed for unemployment insurance saw their claims approved at much lower rates than white workers; households were more likely to experience delayed or missed stimulus checks if they had family incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level or if they were Black or Hispanic, and particularly if they were Hispanic and in families with noncitizens.

Such examples highlight the stark disconnect between the intent of federal government support and its outcomes. This not only disproportionately impacts the welfare of vulnerable populations but undermines confidence in the government’s ability to meet its basic objective to protect its citizens. Bipartisan solutions are therefore needed to correct socioeconomic imbalances and to ensure that government programs and services create, and not crowd out, economic opportunity for Americans.

Given the size of our nation’s debt, any new investments or expansions in this space — and other critical areas like climate change and national security — should be paid for. To achieve this, Congress must enact structural reforms that reduce the growth in spending on our federal entitlement programs, update our federal tax code, and modernize social welfare programs to better promote personal savings and wealth creation and incentivize labor market participation.

Attacking the ever-unpopular waste, fraud, and abuse in government programs will not be enough. The only way to get our fiscal house in order is for federal policymakers to weigh competing priorities and make tangible yet difficult choices among them. A new fiscal agenda structured in a prudent way that induces strong economic growth, increases revenues, and protects low- and middle-income Americans is what will bring stability to the long-term budget outlook.

Conclusion

The nation faces a key challenge in providing economic opportunity for every American. While we cannot turn our back on the needed investments the country requires today, we also cannot ignore our $29 trillion (and growing) gross debt. We are on a dangerous path, spending far more than we raise in revenues. At some point, the fiscal dam will break. Over the past 15 years, BPC has found that securing early wins helps build momentum for bipartisan action in various policy areas. We firmly believe that a new fiscal order is needed — one that reflects the important priorities of both political parties and simultaneously tackles equity, competitiveness, investment, and fiscal responsibility. Moreover, such an agenda must be accomplished through achievable changes to the structures in place today.

The U.S. fiscal ship is large and takes some time — both politically and economically — to turn. However, the future health of the economy and the financial wellbeing of Americans will be damaged if we do not act.

-

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, “Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2020 - May 2021,” May 2021. (Back to Citation).

-

Congressional Budget Office, “The 2021 Long Term Budget Outlook,” March 2021. (Back to Citation).

-

Congressional Budget Office, “Monthly Budget Review: September 2021,” October 8, 2021. (Back to Citation).

-

Committee for a Responsible Budget, “How High Are Federal Interest Payments?” March 10, 2021. (Back to Citation).

-

Congressional Budget Office, “The 2021 Long Term Budget Outlook,” March 2021. (Back to Citation).

-

Ibid (Back to Citation).

-

Jeehoon Han, Bruce Meyer, and James Sullivan, “Income and Poverty in the COVID-19 Pandemic,” American Enterprise Institute, June 22, 2020. (Back to Citation).

-

Ben Gitis, “Survey Points to Potential Racial Disparities in Approval Rates for Unemployment Insurance Claims,” Bipartisan Policy Center, July 30, 2020. (Back to Citation).

-

Janet Holtzblatt and Michael Karpman, “Who Did Not Get the Economic Impact Payments by Mid-to-Late May, and Why?” Urban Institute, July 2020. (Back to Citation).

-

Luci Manning, “Reconciliation Must Adhere to Guiding Principles,” Bipartisan Policy Center, October 18, 2021. (Back to Citation).

About the Author

Jason J. Fichtner is Vice President & Chief Economist at the Bipartisan Policy Center. He is also a Senior Fellow with the Alliance for Lifetime Income and the Retirement Income Institute, as well as a Research Fellow with the Center for Financial Security at the University of Wisconsin. His research focuses on Social Security, federal tax policy, federal budget policy, retirement security, and policy proposals to increase saving and investment. Fichtner is on the Board of Directors for the National Academy of Social Insurance (NASI), where he serves as Treasurer.

Previously, he was a Senior Lecturer of International Economics and an Associate Director of the International Economics and Finance (MIEF) program at Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) where he taught courses in public finance, behavioral economics and cost-benefit analysis. Prior to SAIS, Fichtner was a Senior Research Fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Fichtner also served in several positions at the Social Security Administration, including as Deputy Commissioner of Social Security (acting), Chief Economist, and Associate Commissioner for Retirement Policy. He also served as a Senior Economist with the Joint Economic Committee of the US Congress, as an Economist with the Internal Revenue Service, and as a Senior Consultant with the Office of Federal Tax Services at Arthur Andersen, LLP.

His work has been featured in the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, Investor’s Business Daily, the Los Angeles Times, the Atlantic, and USA Today, as well as on broadcasts by PBS, NBC, and NPR.

Fichtner earned his BA from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; his MPP from Georgetown University; and his PhD in public administration and policy from Virginia Tech.

Fichtner is the author of "The Hidden Cost of Federal Tax Policy" and the editor of "The Economics of Medicaid."

Shai Akabas is BPC’s director of economic policy. He has conducted research on a variety of economic policy issues, including the federal budget, retirement security, and the financing of higher education. Akabas joined BPC in 2010 and staffed the Domenici-Rivlin Debt Reduction Task Force that year. He also assisted Jerome H. Powell, now Chairman of the Federal Reserve, in his work on the federal debt limit. For the past several years, Akabas has steered BPC’s Commission on Retirement Security and Personal Savings, co-chaired by former Senator Kent Conrad and the Honorable James B. Lockhart III.

Akabas has been interviewed by publications including The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal, and has published op-eds in The Hill and The Christian Science Monitor. He has been featured as an expert guest several times on C-SPAN’s Washington Journal.

Prior to joining BPC, Akabas worked as a satellite office director on New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s 2009 campaign for reelection. Born and raised in New York City, he received his B.A. in economics and history from Cornell University and an M.S. in applied economics from Georgetown University.

Expert Views

America's Fiscal and Economic Outlook

We asked twelve leading experts to share their views on the most important fiscal and economic questions facing America.

Their insights help illuminate and improve the understanding of this critical moment, with our economy in recovery, our debt rising unsustainably, and our nation still grappling with a devastating pandemic.

Download the ebook version of all the papers in the series.