Government safety net and income security programs are a cornerstone of our economy, society and federal budget. Social Security and Medicare are America’s largest social programs, providing critical retirement and health benefits to millions. As a result of an aging population and rising healthcare costs, both Social Security and Medicare are on an unsustainable path.

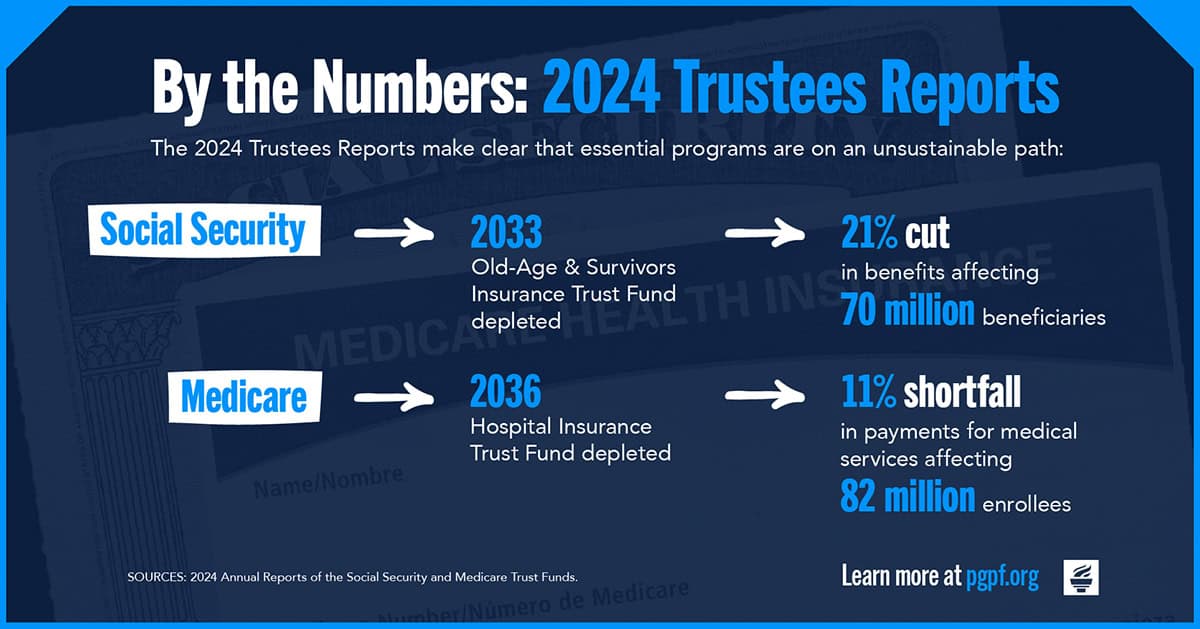

Every year, the Social Security and Medicare trustees provide a report on these programs’ finances and outlook. The latest reports project that Social Security’s Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund will become depleted in 2033 and Medicare’s Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund will become depleted in 2036. At those points, benefits for the respective programs would face significant and sudden automatic cuts, unless lawmakers make reforms before then.

- If lawmakers allow Social Security’s OASI trust fund to become depleted in 2033, 70 million beneficiaries would face across-the-board benefit cuts of 21 percent. That would amount to an average benefit cut of $16,500 per year for the typical couple.

- If lawmakers allow Medicare’s HI trust fund to become depleted in 2036, there would be an 11 percent cut in payments to hospitals and other providers.

The good news is that it is entirely within policymakers’ control to shore up Social Security and Medicare and preserve them for the future. Doing so will not only protect millions of beneficiaries — and especially our most vulnerable citizens — but will provide stability and strength to our fiscal and economic outlook.

Other Social Programs:

In addition to Medicare and Social Security, there are a range of social programs serving Americans, including spending programs and tax benefits:

- Health programs — including Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and premium tax credits for low- and moderate-income people.

- Income Security Programs — including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Supplemental Security Income, Unemployment Compensation, the refundable portion of the Earned Income and Child Tax Credits.

Lawmakers do not provide specific funding levels for these social programs. Instead, they specify the rules of eligibility for benefits as well as the type and level of benefits that each person can receive. For example, the unemployment insurance program has eligibility criteria that, once met, allow an individual to receive a certain level of benefits. Total spending on the program depends on the number of people who file for unemployment, not on a fixed amount of funding set by lawmakers.

Policy Options

Many policy solutions exist for improving the financial outlook of Social Security’s retirement program.

Increasing Social Security’s Payroll Tax Rate

One option to help shore up Social Security’s long-term solvency would be to increase the payroll tax rate, which is currently 12.4 percent (half paid by employees and half by employers) on wage earnings subject to the tax. In 2024, only earnings up to a maximum of $168,600 will be taxed.

According to an analysis from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB), increasing the payroll tax by 1 percentage point (from 12.4 percent to 13.4 percent) could raise $1 trillion in new revenues for Social Security over a 10-year period and shrink the program’s 75-year shortfall gap by 28 percent. Another analysis from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the same 1 percentage point increase would have a more modest revenue effect, raising $712 billion over 10 years.

Increasing or Eliminating the Social Security Tax Cap

Another policy option to increase revenues for Social Security is to raise or eliminate the cap on the amount of income subject to the Social Security tax. In 2024, workers pay Social Security tax on only the first $168,600 of income. According to CRFB, increasing the taxable income limit subject to the Social Security tax to $350,000 could generate around $830 billion in new revenues over the next 10 years, closing 22 percent of Social Security’s 75-year solvency shortfall. The same analysis projects that eliminating the Social Security tax cap altogether could raise $1.8 trillion in new revenues for the program over 10 years and close the 75-year solvency gap by 68 percent.

Reducing Benefits

Another solution for improving the solvency of Social Security is to change the amount that retirees can receive when they first apply for benefits. Many proposals combine a reduction in benefits for high earners with an increase in benefits for lower earners. This is known as "progressive price indexing.”

Other options include slowing the growth of retirees’ benefits over time by changing the cost-of-living index. Many economists believe that Social Security uses an index that overstates inflation, so benefits grow faster than the true cost of living. They propose replacing the current index with chained-CPI, which is a more accurate measure of inflation.

Importantly, most proposals that reduce benefits exempt those individuals who are in retirement, or near retirement (i.e., 55 years old and above). Many policymakers feel that this is a fairer way to reform the program, giving people sufficient time to prepare for their retirement.

Gradually Raising the Retirement Age

Given that overall life expectancy continues to increase, many policymakers have called for a modification to the program under which the full retirement age is gradually raised and pegged to average life expectancy. According to an analysis from CRFB, gradually increasing the full retirement age by two months per year until it reaches 69 and then indexing it for changes in overall life expectancy would save $90 billion over a 10-year period, but much more in future decades. CRFB estimates that this change would close more than half of the structural mismatch between Social Security’s revenues and spending in the long run. There are also important options to consider that would exempt those whose work includes demanding physical labor, as well as considerations for differences in life expectancy among different groups of Americans.

Including State and Local Government Employees in Social Security

Under current law, state and local governments can opt out of enrolling their employees in Social Security if they instead provide a separate retirement plan, such as a pension. Today, roughly one-quarter of all state and local government employees are not covered by Social Security, and thus are not subject to the Social Security payroll tax. According to a 2020 CBO analysis, expanding Social Security coverage to include all state and local government employees hired after December 31, 2020, would raise $101 billion in new revenues for the program over a 10-year period. It would, however, also increase spending over time for these beneficiaries.

Policy Options

Thoughtful health policy reforms can address fiscal concerns, protect Medicare beneficiaries, and enhance efficiency and outcomes in the overall healthcare system.

Allowing Medicare to Negotiate Prices of Prescription Drugs

The United States spends about twice the average of other wealthy countries per capita on healthcare, which is partly due to high drug costs. Prior to enactment of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), Medicare was prohibited from negotiating prescription drug prices directly with manufacturers, which contributed to the government having to pay for medications at relatively higher prices. The IRA authorizes the federal government to directly negotiate prices for a limited number of drugs covered by Medicare. Under the enacted provisions, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) will be allowed to negotiate prices for up to 10 drugs in 2025, an additional 15 in 2027, 15 more in 2028, and finally another 20 drugs in 2029 and after.

Overall, allowing HHS to negotiate drug prices in Medicare is expected to reduce costs for the federal government and for consumers. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that all of the provisions related to prescription drugs in the IRA will save the federal government $286 billion over the upcoming decade. Of that, the price negotiating provision is projected to reduce spending by nearly $102 billion over 10 years.

Reducing Federal Healthcare Subsidies

There are a number of available reforms to limit federal healthcare spending. For Medicare, options include raising the eligibility age, increasing premiums, or increasing taxes on benefits, which would reduce the level of financial assistance provided to higher income beneficiaries. Federal costs could also be limited by imposing caps on spending for Medicaid and subsidies for health insurance.

Changing the Structure of Federal Healthcare Programs

These options would redesign federal healthcare programs and include:

- Combining Medicare’s Part A hospital care program with Part B ambulatory services

- Reforming coverage for low-income individuals who need long-term and high-cost care and are eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (known as "dual eligibles")

- Converting Medicare into a premium support program that would allow beneficiaries to purchase insurance through health insurance exchanges

Additional Social Programs Resources:

- Social Security Administration, Office of the Chief Actuary's Estimates of Proposals to Change the Social Security Program

- Peter G. Peterson Foundation, Social Security Reform: Should We Raise the Retirement Age?

- Peter G. Peterson Foundation, Social Security Reform: Options to Raise Revenues

- Peter G. Peterson Foundation, Social Security Reform: Should We Reduce Benefits?