The COVID-19 pandemic had a devastating effect on America’s economy, with millions of workers losing their jobs. To help assist those in need, lawmakers enacted a range of expansions to unemployment insurance (UI) between March 2020 and September 2021, including increasing weekly support, extending the amount of time that workers could remain in the program, expanding coverage to self-employed workers, and subsidizing programs for workers whose hours were reduced.

Now that the need for UI is rapidly returning to its pre-pandemic level, it is worth considering lessons learned over the past two years and how lawmakers might draw from such evidence. The Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC) analyzed the approaches taken to the massive and rapid increase in unemployment and outlined several key takeaways for providing support in the future.

The Pandemic’s Devastating Effect on Employment Has Mostly Receded

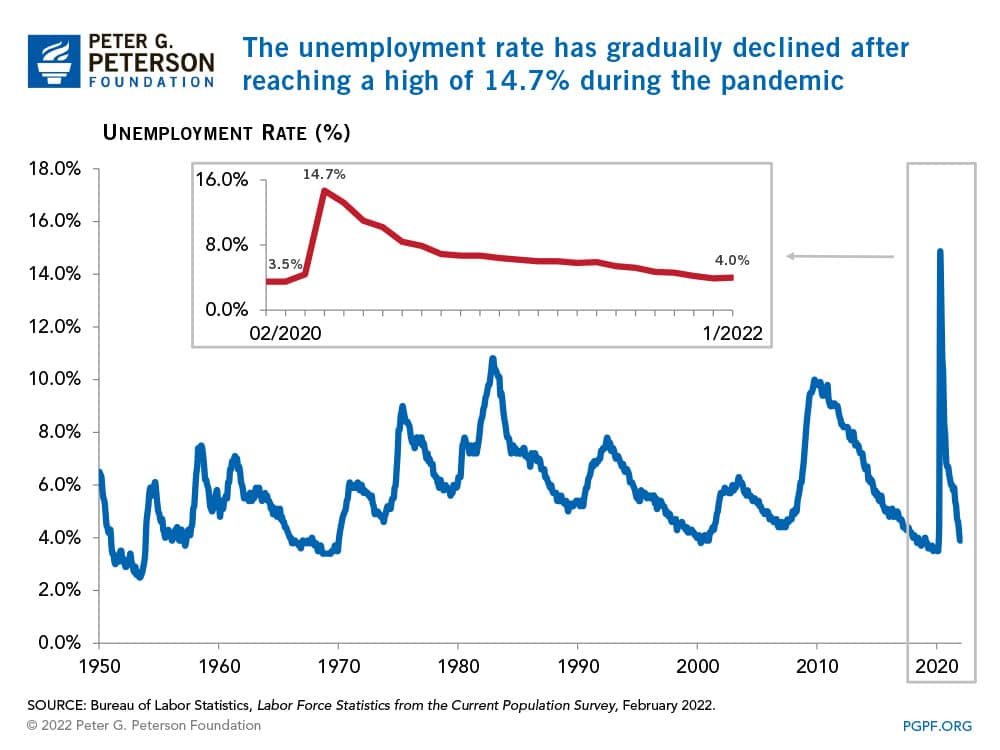

The economic damage induced by the pandemic was evident soon after COVID-19 was detected in the United States. In fact, as stringent public health measures were implemented and nonessential businesses braced for a sudden loss in revenues, the unemployment rate climbed from 3.5 percent in February 2020 to 14.7 percent in April 2020 — far surpassing the peak unemployment rate during the Great Recession.

As public health conditions improved and businesses began to rebound, the unemployment rate has fallen gradually. Almost two years later, the unemployment rate is now around 4 percent.

Lesson 1: Expanded Unemployment Benefits and Eligibility Provided Quick Relief — But Also a Disincentive to Return to Work

In quickly responding to the unique challenges posed by the pandemic, lawmakers both increased UI benefits and extended the coverage period for all eligible workers.

In particular, lawmakers funded a flat supplement in extra UI benefits for covered workers, initially $600 per week and later reduced to $300 per week in August 2020, on top of regular benefits. To ensure that unemployed workers were covered for long enough, lawmakers also extended eligibility from 13 weeks to 53 weeks. Those expansions provided immediate relief and were simple for state workforce agencies to administer, but also resulted in nearly half of jobless workers collecting at least as much in unemployment compensation as their prior wages. As a result, a flat supplement may have discouraged some workers from returning to the labor force.

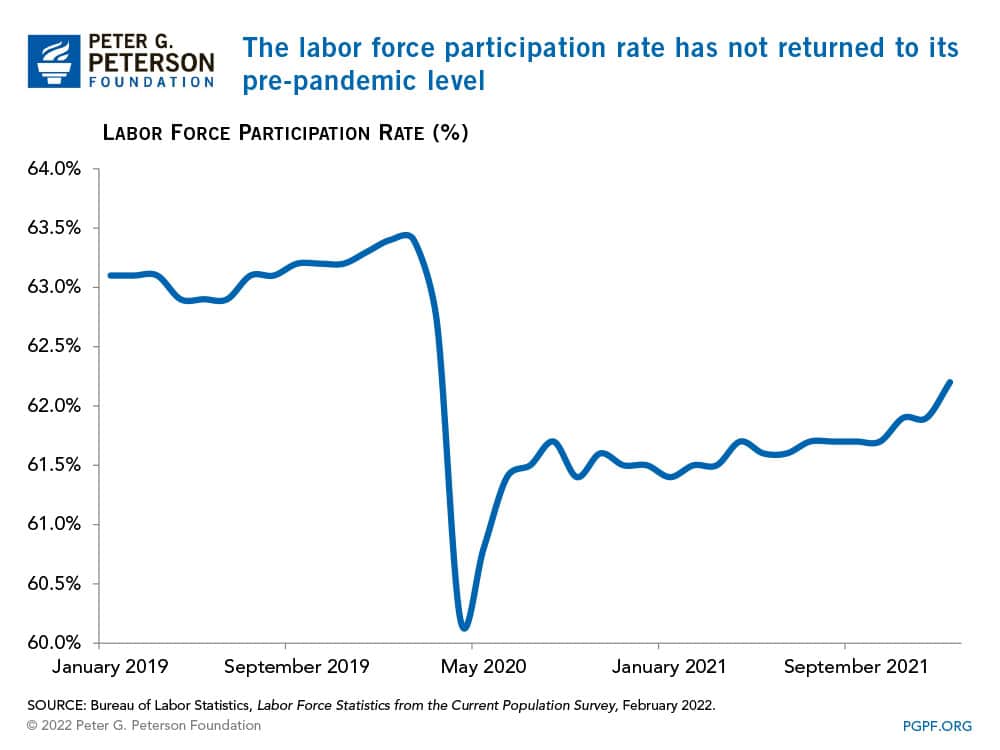

The labor force participation rate has remained relatively stagnant for over a year and has failed to return to its pre-pandemic level. That result is explained by a variety of factors — including fears of COVID-19 case spikes and caregiving responsibilities — but BPC suggests that the generous supplemental funding has also contributed to the stagnation.

A flat supplement also failed to account for regional variation in wages and economic performance. It became increasingly clear that public health conditions in one part of the country were often unrelated to others areas. In this respect, BPC suggests that more UI support should have been directed to regions experiencing COVID-19 case spikes, while phasing out support in regions with low transmission. In addition, UI support could have been adjusted to account for regional variations in wages and purchasing power, which vary greatly across the country. Lawmakers should consider whether there are other ways to provide immediate and targeted relief that take those factors into account.

Moreover, federal UI expansions expired suddenly on September 6, 2021, with The Century Foundation finding that 7.5 million unemployed workers completely lost coverage on that date. Instead of that unemployment benefit cliff, BPC suggests that UI expansions should have been phased out, with additional federal funds provided to assist jobless workers to regain employment.

Lesson 2: Unemployment Support for Self-Employed Workers Is Key to Modern Gig Economy

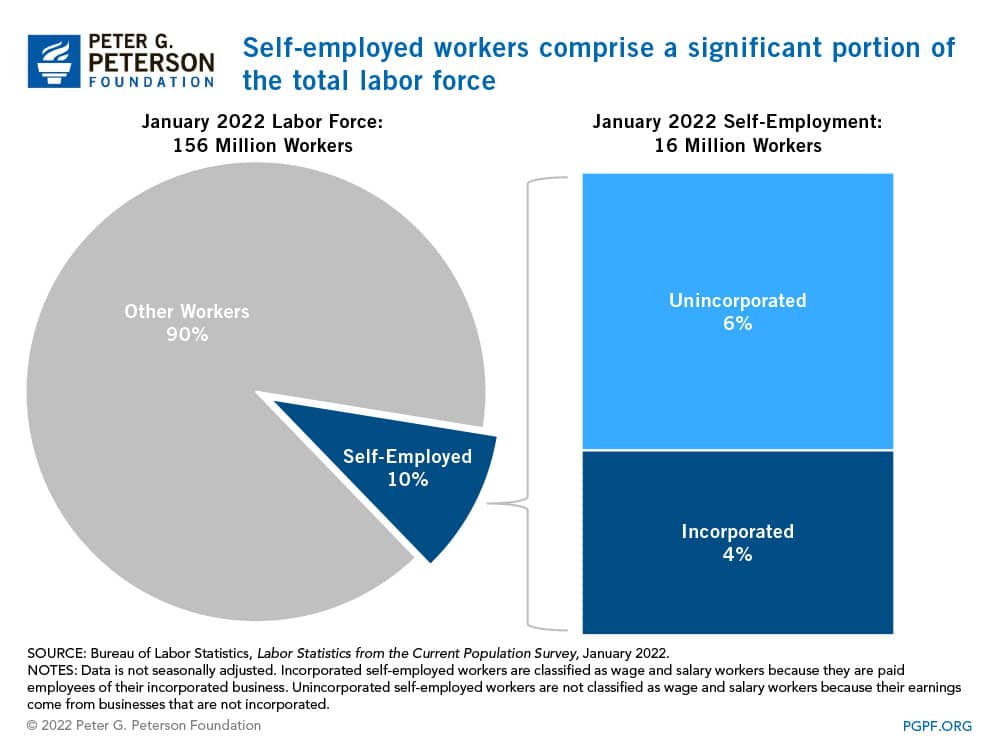

One of the most significant expansions of UI was extending eligibility to self-employed workers who lost business, were furloughed, or otherwise unable to work for reasons related to COVID-19. Those workers are not covered by traditional UI, despite the fact that they now make up a substantial portion of the workforce.

In January 2022, the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that there were nearly 16 million self-employed workers, accounting for about 10 percent of the nation’s total workforce. Those workers perform a wide variety of roles, including consulting and other professional services for incorporated businesses, as well as unincorporated independent contractors who work in the gig economy.

Considering the growth of the gig economy in recent years, BPC suggests that lawmakers consider whether UI eligibility should be permanently expanded to include self-employed workers. Doing so could be an important way to modernize UI to meet the demands of today’s economy and protect those workers during economic downturns, but it would also require administrative innovations to certify eligibility and prevent misuse.

Lesson 3: Short-Time Compensation Programs Are Complex, but May Provide More Targeted and Effective Incentives

Another important expansion of UI included federal support for Short-Time Compensation (STC) programs. STC is a form of UI in which employees whose hours have been reduced, but remain employed, can receive a prorated portion of unemployment benefits. Given fears about traditional UI discouraging work, research from Japan and across Europe finds that STC can provide an incentive for workers to remain in the workforce during an economic recession.

Between March 2020 and September 2021, the federal government fully subsidized STC in the 25 states that had existing operational programs and partially covered costs for other states to create new STC programs. States had considerable autonomy over such programs, and as a result, there was significant variation in their terms and requirements.

Employers may be reluctant to participate in STC programs because of the complexity of negotiating between different requirements across states as well as increased UI tax burdens necessary to cover additional program beneficiaries. Nevertheless, BPC recommends lawmakers consider whether STC programs could become a permanent method to stabilize employment during future economic downturns.

Lesson 4: Antiquated State UI Systems Complicated Delivery of Benefits

Pandemic-related UI expansions were made at the federal level, but UI is administered by state workforce agencies. Heightened claims and antiquated state systems complicated delivery of UI benefits to eligible workers. Even in February 2021, nearly a year into the pandemic, just six states reported meeting the federal standard of providing benefits to 87 percent of applicants within three weeks.

In addition, UI expansions also exposed state workforce agencies to a considerable amount of fraud. The Department of Labor’s Office of Inspector General estimates that more than 10 percent of pandemic-related UI benefits, $87.3 billion, will ultimately have been spent improperly, a significant portion of which is largely attributable to fraud. An analysis by ProPublica found that from March to December 2020, the number of initial UI claims equated to 68 percent of the country’s labor force, despite the fact that the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that just 23 percent of American workers were out of a job or underemployed at the peak of the pandemic. Although that can be partly explained by workers who became unemployed multiple times during that period, fraudsters likely account for a significant portion of the discrepancy. For example, Vermont reported that up to 90 percent of UI claims in some months were fraudulent. Other states have also reported significant levels of fraud, with 43 percent of claims in Rhode Island and 14 percent in Texas suspected to be fraudulent during certain periods.

Those findings make clear that more needs to be done to protect the integrity of UI programs and ensure that benefits are distributed promptly to protect the financial wellbeing of unemployed workers. The Office of Inspector General recommends that Congress pass legislation requiring state workforce agencies to cross-match claimants with existing national databases to identify fraud.

Unemployment Insurance in the Future

Countercyclical fiscal support, such as unemployment insurance, can be a critical tool of the government to ease suffering from economic downturns and hasten a recovery. The more targeted and strategic those programs are in their design, the more cost-effective and thorough they will be in meeting those goals.

The past two years of the pandemic offer valuable lessons for lawmakers in designing UI expansions that balanced the need to provide support for jobless Americans while also not discouraging workers from returning to employment when appropriate.

Looking ahead, options to consider for the UI program include whether permanent reforms to UI that extend eligibility to self-employed workers and promote STC programs are worthwhile. In addition, the government can consider changes to UI to better promote effectiveness, targeting of populations in need, and modernization of UI administration.

Image credit: Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Further Reading

The Fed Reduced the Short-Term Rate Again, but Interest Costs Remain High

High interest rates on U.S. Treasury securities increase the federal government’s borrowing costs.

What Types of Securities Does the Treasury Issue?

Let’s take a closer look at a few key characteristics of Treasury borrowing that can affect its budgetary cost.

Experts Identify Lessons from History for America Today

A distinguished group of experts to evaluate America’s current fiscal landscape with an historical perspective.