Here Are Some Holes in the Social Safety Net That the Pandemic Highlighted

Last Updated May 21, 2021

As a result of the economic downturn following the outbreak of coronavirus (COVID-19), many Americans have relied on the social safety net for support. The safety net is a patchwork of various programs that provide in-kind or cash benefits, generally to low-income households. Those programs have been a vital lifeline for millions of economically vulnerable Americans, especially as the government took quick action to enhance benefit levels and extend eligibility during the pandemic.

The unprecedented size of the economic disruption, however, put the safety net to the test, revealing weaknesses that often prevented support from reaching some of the neediest families in a timely manner. By examining the effectiveness and shortcomings of those programs during the crisis, policymakers have an important opportunity to improve them for the future. Below, we review some key gaps revealed by the pandemic in three of the largest safety net programs: Unemployment Insurance (UI), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, also known as Food Stamps), and Medicaid.

Delays and Administrative Strains in Unemployment Insurance Caused Uncertainty

UI is a joint federal-state program that provides temporary benefits to those who lost their jobs through no fault of their own. As the pandemic triggered unprecedented levels of unemployment, policymakers created new programs to enhance benefit levels and extend eligibility to those who did not qualify for traditional UI (such as self-employed workers or individuals with limited work history). While such legislative changes expanded program size and access, many recipients still faced uncertainties in the amount and duration of assistance because payments from emergency programs were subject to lags in implementation and were established to cover a short period of time.

For example, the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) was a program created by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) that provided an additional $600 in weekly benefits. The program began in early April 2020, initially expired at the end of July 2020, and was revived at a lower level five months later. Such fluctuations create uncertainty over benefit levels that undermines the financial stability intended for families during economic downturns; one study has found that after the initial expiration of the FPUC benefits, missed housing payments increased by 11 percentage points compared to when FPUC was active.

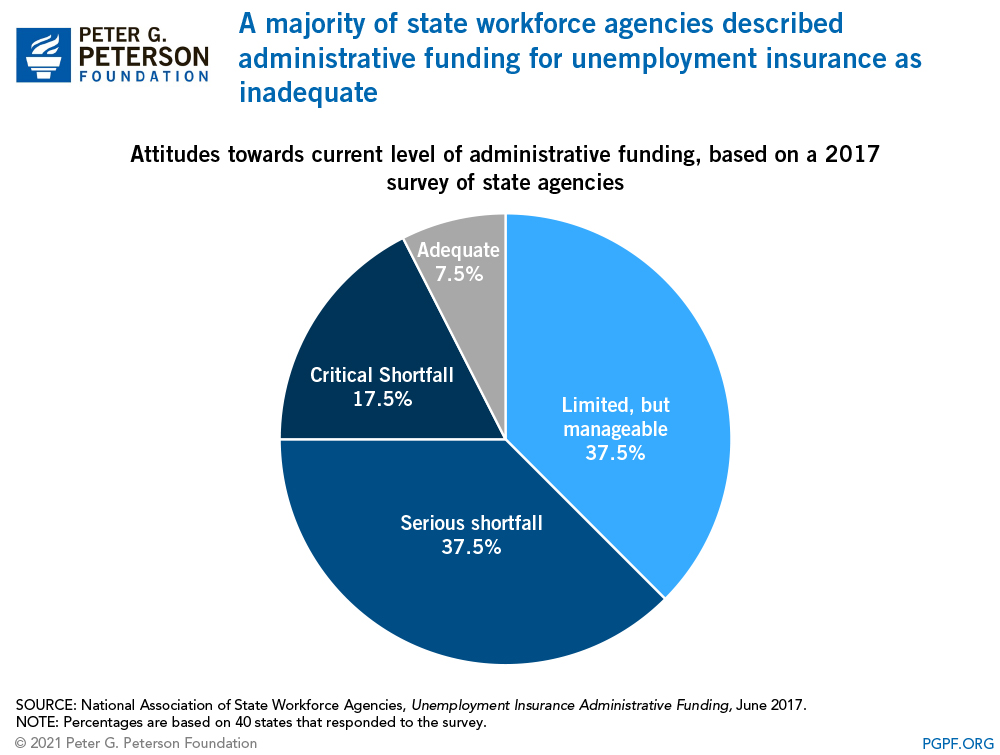

In addition, the expansion of benefits and increase in demand for assistance during the pandemic placed a significant strain on state administrative offices, which were already inadequately funded and using outdated technology. Consequently, some payments were significantly delayed. For example, in Florida, only 5 percent of applicants received unemployment benefits in the first month of the pandemic, largely because of administrative challenges. Such delays in payments can be particularly consequential for low-income families, who may be living paycheck to paycheck.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Was Slow to Implement Adjustments

SNAP, which provides low income families with money to buy food, also saw significant increases in participation due to higher demand during the recession as well as legislative changes that raised benefits and eased eligibility requirements. Despite the rise in participation and spending on the program, food insecurity is still well above pre-pandemic levels — partly because many of the neediest households did not receive additional support.

The CARES Act allowed states to issue maximum allowable SNAP benefits to households, but that provision did not increase payments for the 40 percent of recipients who were already receiving maximum benefits. In late December 2020, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 eventually raised maximum benefits by 15 percent, and the American Rescue Plan, enacted in March 2021, extended that increase through September 2021, but those low-income households had to wait many months for additional assistance.

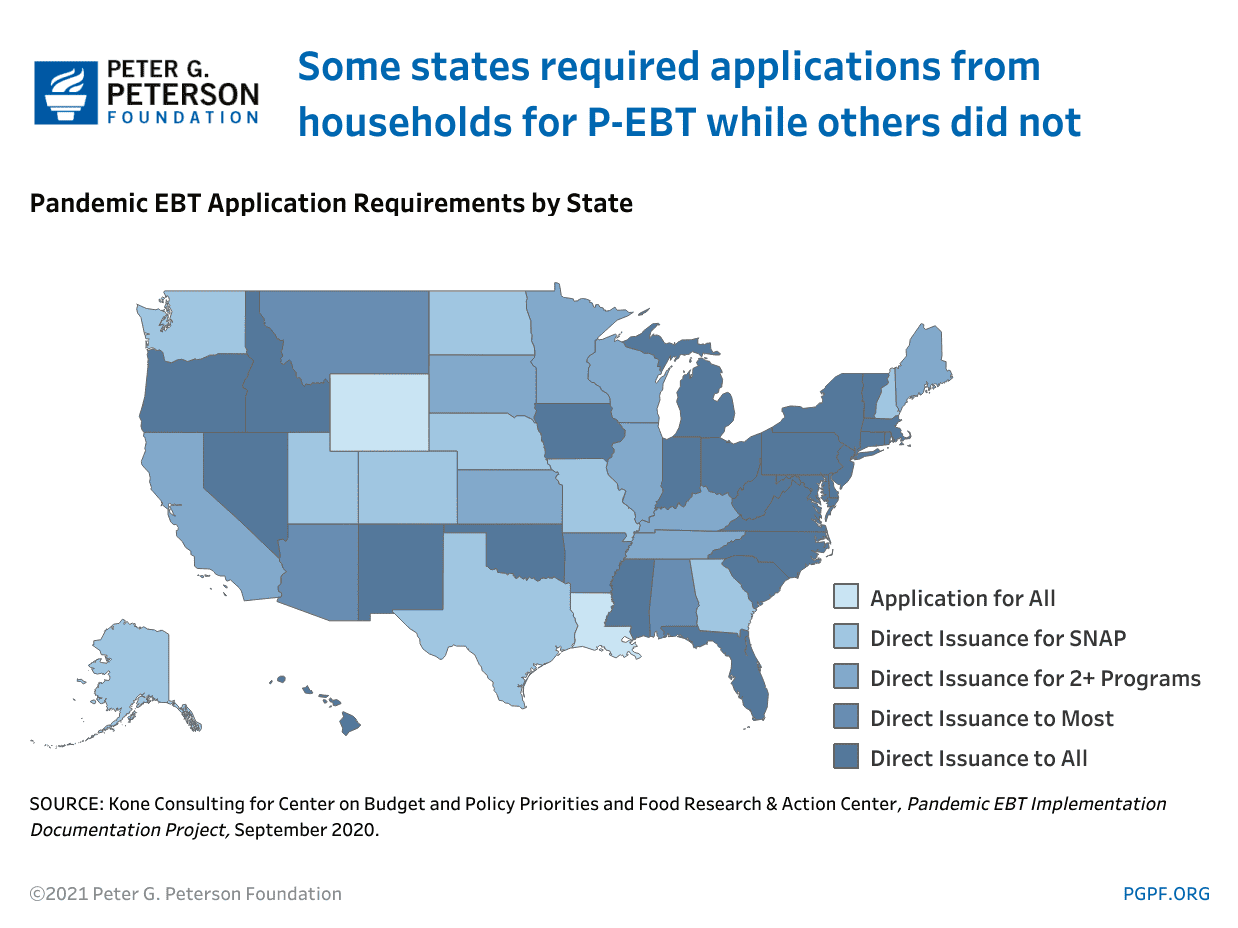

Implementation of new programs under SNAP also caused administrative burdens that led to further delays in the rollout of those benefits. For example, states had to create new structures to implement the Pandemic-Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT) program, a new food relief program for children whose schools were closed or that were operating with reduced attendance due to the pandemic. As a result, three months after the program was created, only 12 states had started the program and only 15 percent of eligible children were receiving benefits. Additionally, states took different approaches to distributing benefits due to differences in the availability of information. While some states automatically issued P-EBT benefits to all eligible children because they had sufficient information in their systems, others required families to apply for them.

Challenges specific to the COVID-19 public health crisis also revealed weaknesses in the program. At the onset of the pandemic, only six states were participating in the Online Purchasing Pilot, which allows SNAP participants to purchase their groceries online. The need for social distancing eventually led to a rapid increase in participation in the program, but many states took several months to implement the new online purchasing technology. Furthermore, the program prohibits SNAP beneficiaries from using benefits to pay for delivery, which may limit utilization of the service.

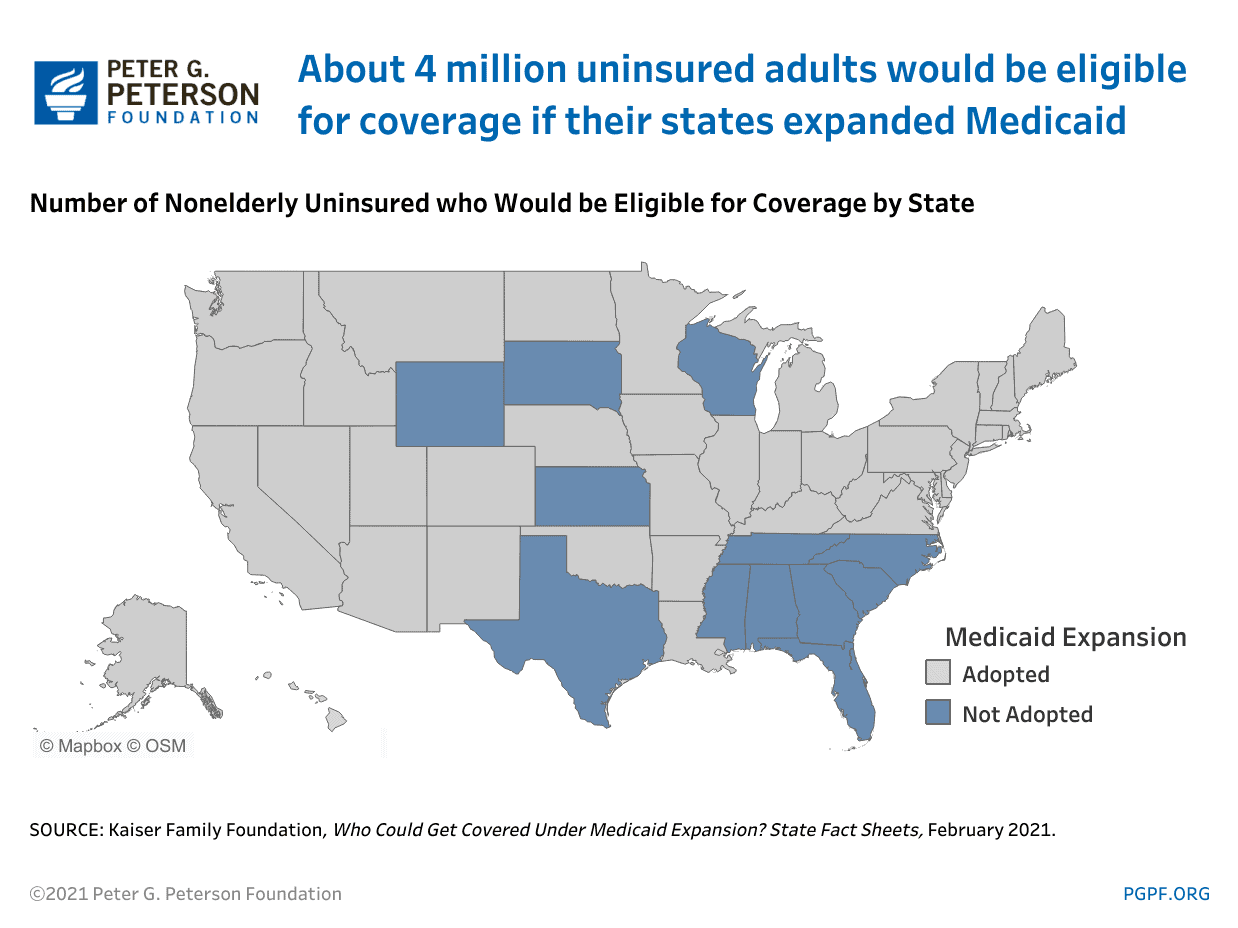

Millions More Workers Could Have Benefitted from Medicaid

As the massive increase in unemployment caused millions of workers to lose employer-sponsored insurance during the pandemic, a significant number of them restored their health coverage through Medicaid, a joint federal-state program that provides health insurance primarily to low-income individuals. However, many people, particularly young adults, near or under the federal poverty level are not eligible for coverage in states that have not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (unless they are pregnant or have disabilities). As such, those people lack affordable health coverage options. While COVID-19 provisions increased federal funding for state Medicaid programs and prevented states from cutting existing enrollees, they did not necessarily expand access to the program.

Furthermore, the need to apply and comply with various requirements has been a significant barrier for many who are eligible to enroll in the program. Such requirements are particularly disadvantageous for the lowest-income Americans, who may lack the economic resources, time, and skills to navigate the application process. Even those who are already enrolled must continue to prove their eligibility by responding to requests for information. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, enacted in March 2020, near the beginning of the pandemic, prohibited states from terminating existing Medicaid coverage for the duration of the public health emergency; once the program returns to its normal operations, though, administrative burdens on state Medicaid agencies and enrollees may cause eligible people to lose coverage.

Other COVID-19 Measures Provided Additional Support

In addition to the enhancement of existing programs, many new programs created in response to COVID-19 played a critical role in assisting families adversely affected by the pandemic; however, they also faced design and administrative challenges. The first round of stimulus checks, for example, was delivered mostly through direct deposit in order to deliver benefits quickly. Benefits were therefore distributed significantly faster than during previous recessions, but initially excluded many low-income families who lacked access to bank accounts or whose income was below the tax filing threshold. Six months after enactment of the CARES Act, approximately 9 million people still had not received their stimulus payments.

Another example is the federal eviction moratoriums, which helped prevent struggling renters from losing their homes. While the moratoriums prevented eviction, analysts argue that they did not do enough to help renters with their unpaid rent or help the many small landlords who rely on rental income. The December relief package and the American Rescue Plan eventually provided federal funds for rental assistance, but those came months after the moratoriums were put in place. State and local rental assistance programs provided some help during that period but fell significantly short of the estimated need.

What Did the Pandemic Teach Us About the Social Safety Net?

Policymakers enacted significant, critical programs in response to the pandemic, and have an important opportunity to examine and learn from areas where those programs fell short and areas where they succeeded. While the U.S. social safety net was largely successful in offsetting many of the damaging effects of COVID-19, the pandemic has also revealed several of its key shortcomings in responding to a crisis. Due to the scale of the disruption caused by COVID-19, the federal government took quick action to enhance programs through ad hoc legislative adjustments — which often caused administrative strains that delayed the rollout of payments.

Other issues arose from weaknesses in the safety net that existed even before the pandemic. Many experts argue that to be better prepared for such crises, programs should be equipped with capabilities to automatically expand during recessions (such as increases in SNAP benefits). Other proposed reforms call for more permanent changes, including increased access to programs by expanding eligibility (such as to gig or part-time workers for UI) and structural changes to state financing of safety net programs. Policymakers should consider such reforms to better provide relief to needy Americans both during crises and in normal times.

Image credit: Photo by Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

Further Reading

A Bipartisan Roadmap for Social Security Reform

Lawmakers are running out of time before automatic reductions to benefits are activated; the Brookings Institution plan is a valuable contribution to the policy discussion.

U.S. Population Growth Is Slowing Down — Here’s What That Means for the Federal Budget

Understanding how demographic challenges contribute to the United States’ fiscal challenges can help policymakers adopt fiscally sustainable policies.

What Is the Farm Bill, and Why Does It Matter for the Federal Budget?

The Farm Bill provides an opportunity for policymakers to comprehensively address agricultural, food, conservation, and other issues.