You are here

Summary of President Obama’s Long-Term Deficit and Debt Reduction Framework

Introduction

The President’s budget for Fiscal Year 2012 contains spending and revenue proposals for the remainder of the current year, as well as the coming decade. The budget identifies the changes the Administration proposes to current laws governing federal programs and activities, as well as to tax laws. The budget process now moves to the Congress, where it will be up to members of the House and the Senate to agree upon a Congressional Budget Resolution to guide the development of legislation to fund federal programs and raise revenues.

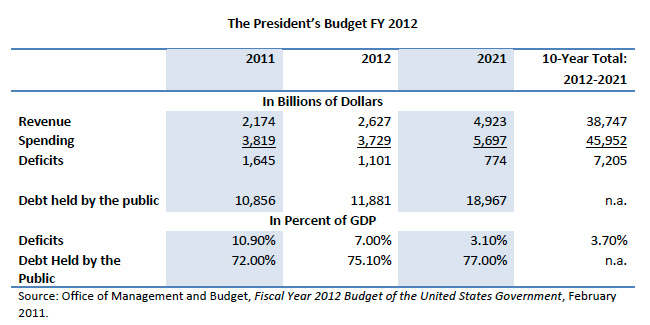

For the current year, the budget proposes spending of $3.8 trillion and revenues of $2.1 trillion, resulting in a deficit of more than $1.6 trillion, equal to about 11 percent of the overall economy (or gross domestic product—GDP), which would be the highest deficit since World War II. For the 2012 to 2021 period, the budget would produce deficits that would gradually decline to about 3 percent of GDP. In dollar terms, the gap between revenues and spending would fall to $607 billion in 2015 before rising again. In 2015, that deficit would exceed projected spending for Medicare or projected revenues from corporate taxation.

Highlights

Economic Assumptions

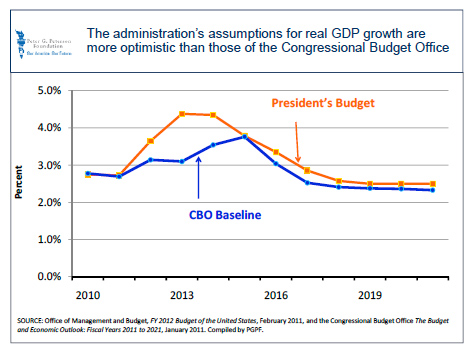

Although the administration sees modest economic growth this year, it anticipates that the economy will pick up significantly next year and reach 4.4 percent growth in 2013, which helps to boost revenues in its projections.

Economic forecasting is inherently uncertain, but forecasts can be evaluated by comparing them to others. The administration’s 10-year outlook for real GDP is noticeably brighter than that of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) (see above). On average, real GDP grows about 0.35 percentage points faster in the administration’s forecast from 2011-2021. The largest difference is found in 2013, when the administration expects the economy to grow 1.3 percentage points faster than CBO does.

The Federal Reserve also compiles a number of forecasts of macroeconomic performance. The administration’s projections for real GDP from 2011-2013 are within the central tendency of these projections from the Federal Reserve, though they are at the top of the Federal Reserve’s central tendency in 2013. The administration is also more optimistic in 2012 than the average of private forecasters, as calculated by the Blue Chip Economic Indicators.

1 The members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors and the presidents of the Federal Reserve Banks, all of whom participate in deliberations of the Federal Open Market Committee, submit projections for output growth, unemployment, and inflation for the years 2010 to 2012 and over the longer run. The central tendency of this projection excludes the three highest and three lowest projections for each variable in each year.

Despite the stronger economic growth, the administration does not expect the job market to recover quickly. The unemployment rate remains above 7 percent until 2014, and the administration’s views on the unemployment rate are similar to that of the CBO and other forecasters.

Comparing the President’s Budget to Different Baselines

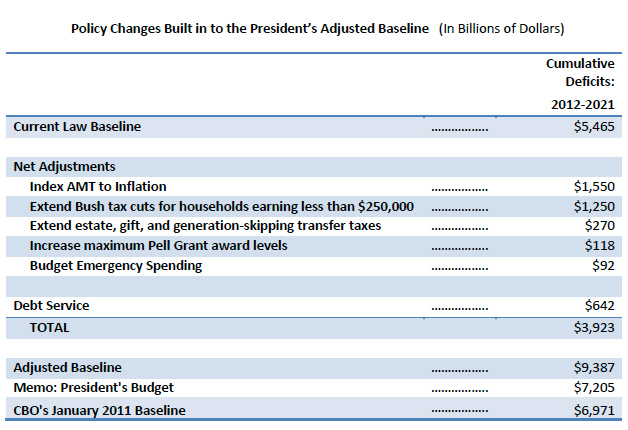

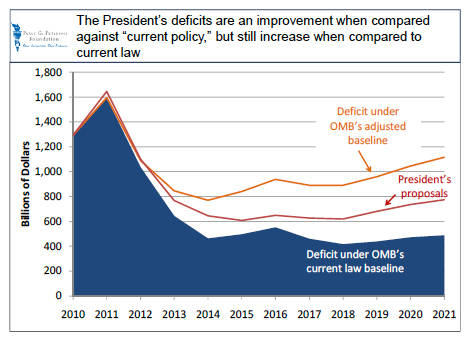

The current law baseline, also known as the Budget Enforcement Act (BEA) baseline, reflects the budget as it would be if no new laws were passed. This baseline establishes a neutral benchmark against which the budget proposals of the President and the Congress can be measured. In addition to the current law baseline, OMB also produces an “adjusted baseline,” which incorporates the policies they think are likely to be enacted in the future, even if they are not in current law.

The deficits projected in this adjusted baseline are significantly higher than in the current law baseline. Compared to the “adjusted baseline,” deficits under the President’s proposal show improvement. However, relative to the current law baseline, deficits under the President’s proposal are higher. Thus, when the budget calculates $1.1 trillion of savings, that number is based on a comparison to the adjusted baseline, not current law.

Policy Proposals

This budget shows restraint, but it does more than just cut spending: it also attempts to find ways to target investments within discretionary spending. While the Administration should be commended for raising concerns about the deficit, the President’s budget stops short of making precise policy recommendations on major defense cuts, Social Security and health care – the biggest components of the budget. Many of the specifics are found in the short- and medium-term proposals that attempt to rebalance government towards productive investments.

Revenues

- Compared to the current law baseline, the budget would reduce revenues by $2 trillion over the 2012-2021 period. This includes the extension of the individual tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 for individual taxpayers making less than $200,000 and couples making less than $250,000; and a 3-year extension of a provision that raises the threshold at which taxpayers are affected by the alternative minimum tax (AMT).

- A permanent fix is proposed for the AMT after three years, but only if offset by other unspecified savings.

- The budget eliminates a slew of corporate tax expenditures and calls for corporate tax reform, which could simplify the tax code and improve growth.

Spending

- The budget emphasizes investments in infrastructure and green technology.

- TRICARE contractor changes

- Modest increases in co-pays, including indexation

- Incentives to purchase lower-cost prescription drugs

- Reductions in subsidies to hospitals that treat military patients

Looking at the Long Term

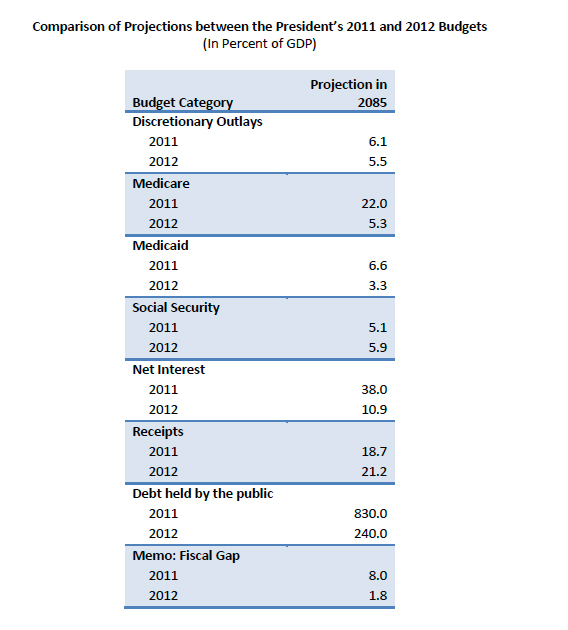

Compared to the President’s proposed budget for Fiscal Year 2011, the proposed budget for Fiscal Year 2012 shows a surprising improvement in the long-term “fiscal gap”—since last year, this gap has gone from 8 percent of GDP to 1.8 percent. (The fiscal gap is the size of changes to revenues or expenditures that would be necessary to stabilize debt as a percentage of GDP over a 75-year period.) Lawmakers and other experts will likely debate the validity of that improvement given the absence of significant proposals to change existing policies. Moreover, even under these optimistic assumptions, the administration projects that federal debt will rise to 117 percent of GDP in 2040 and to 240 percent in 2085.

This table makes clear that much of the projected improvement over the 75-year period is due to changes in the outlook for federal health spending. This year’s budget projects that spending for Medicare will only reach 5.3 percent of GDP in the 75th year of projection, down from last year’s 22 percent. The result is less debt, smaller net interest payments, and a much smaller fiscal gap.

Health Care

As the comparison between the long-term outlooks from last year’s to this year’s budget illustrate, solving the problem of excess health care cost growth is critical to restoring balance in federal finances.

As the chart above indicates, the reduction of growth is due almost exclusively to reductions in the projected size of Medicare. As noted in the Analytical Perspectives, “the growth rate is significantly smaller than…previous projections – a reduction they largely attribute to the ACA [Affordable Care Act].”

Some health policy experts have questioned the sustainability of the spending restrictions in the new law. They note, as CBO does, that the full implementation of the law’s changes to Medicare would limit growth of provider payments, as one example, to a level below that of inflation. Many economists and health policy experts, who may not have directly opposed the law, are similarly uncertain about the government’s ability to follow through on its plans to control the program’s growth. Medicare’s chief actuary offered an unprecedented alternative scenario to a recent report, warning that the long-term savings projections are based on policies that are potentially unrealistic and unsustainable. And it may turn out that they are right. The projections assume that most of the cost-cutting policies will be implemented as designed, maintained over time, and that the underlying assumptions will remain valid and effective—something that might prove difficult under future Congresses with competing priorities.

Conclusion

President Obama’s proposed 2012 budget and the discussion in Congress represent a starting point to begin addressing our nation’s fiscal challenges. Both parties need to go much further. The real threat to America’s long-term economic future is not short-term discretionary spending, but the long-term structural deficits that result in massive interest costs that would burden our nation for decades. To address our long-term fiscal and economic challenges effectively, we need a bipartisan plan that fully tackles all of the major unsustainable areas of the Federal budget. The only way for us to win the future is with a bipartisan plan for the future: a set of sound and sustainable fiscal policies that solve our long-term structural deficits and can be implemented gradually as our economy recovers. Despite the political challenges of reaching bipartisan solutions, the President’s Fiscal Commission is proof that this can be done. It is time for lawmakers from both parties to show leadership by putting our country on a path to economic prosperity and fiscal sustainability.

About the Peter G. Peterson Foundation

The Peter G. Peterson Foundation is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization established by Pete Peterson – businessman, philanthropist, and former U.S. Secretary of Commerce. The Foundation is dedicated to increasing public awareness of the nature and urgency of key long-term fiscal challenges threatening America's future and to accelerating action on them. To address these challenges successfully, we work to bring Americans together to find and implement sensible, long-term solutions that transcend age, party lines and ideological divides in order to achieve real results. To learn more, please visit www.PGPF.org.

2Congressional Budget Office, Letter to The Honorable Nancy Pelosi, March 20, 2010. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/113xx/doc11379/AmendReconProp.pdf